The Artists Confronting Sexual Violence

Laia Abril, Gabrielle Goliath and Lydia Pettit amplify the voices of survivors – and challenge the narratives that silence them

Laia Abril, Gabrielle Goliath and Lydia Pettit amplify the voices of survivors – and challenge the narratives that silence them

American artist Lydia Pettit began painting herself in horror-inspired settings after she was raped as a teenager. In her 2023 Galerie Judin exhibition ‘In Your Anger, I See Fear’, blood-red paintings such as Mercy (2022) and The Seduction (2023) featured the artist wielding steely knives and staring at her own reflection with both terror and ferocity. The show investigated the sharp psychological split between submissive, ‘idealized’ victimhood – demanded by the court system, wider culture and often ourselves – and the intense rage she carried within. Pettit has cited Artemisia Gentileschi as a key influence; the Italian painter’s vicious paintings channelled her own experience of rape and the torture she endured while seeking justice.

‘For years I was trying to perform the “perfect victim” as a means of protection,’ says Pettit. ‘If I never got angry, if I remained meek and compliant, not vengeful, then maybe it wouldn’t happen to me again. That idea of trying to be the right kind of victim led me into even more traumatic situations, because the “perfect victim” is not meant to stand up for themselves. They are a recipient of trauma – and that’s all.’

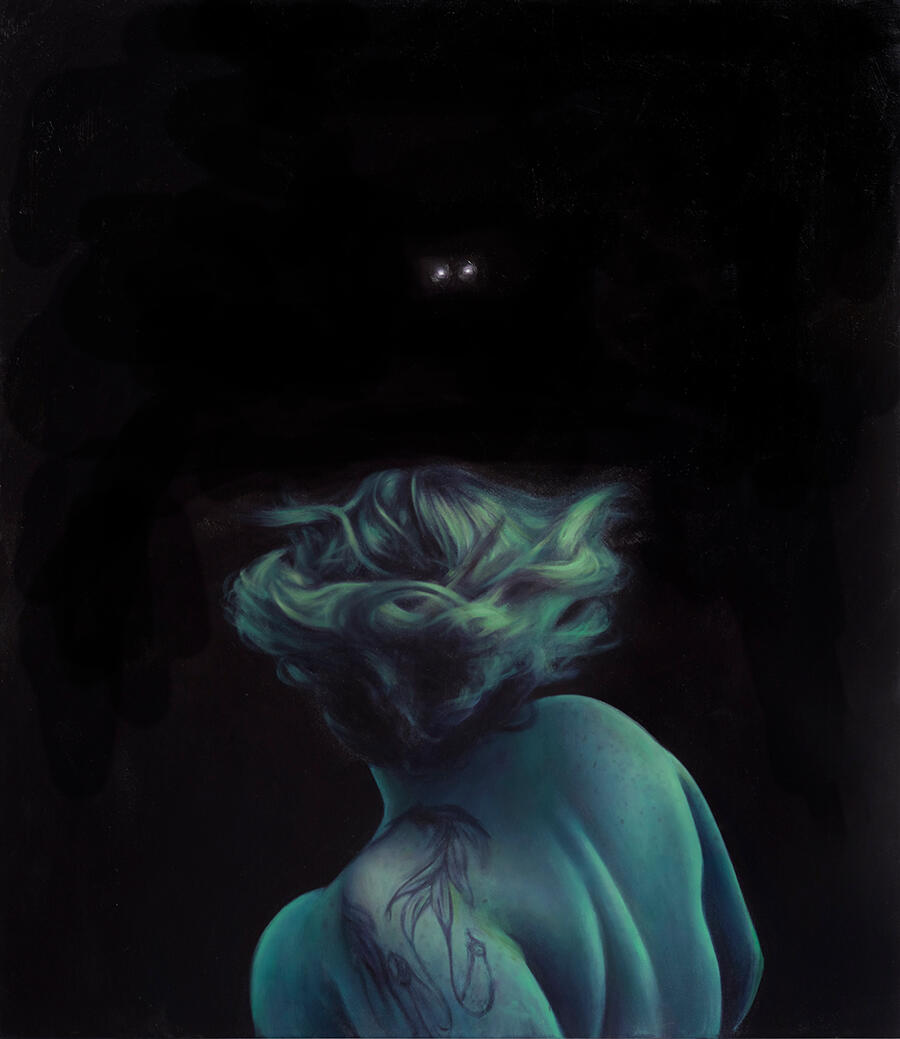

Pettit recently opened a new solo show, ‘E.M.D.R’, at Galerie Judin. The exhibition follows her work with a psychotherapist addressing sexual trauma and online grooming, and features canvases drenched in viridian, cobalt and teal paint. These colours mark a shift from the bloody palette of her previous show, conjuring a more complex emotional landscape that delves deeper into the unconscious. In Surface and Recovered Memory (all works 2025), a sticky black liquid submerges the artist, evoking Jonathan Glazer’s 2013 thriller Under the Skin and her own experience of disturbing a hidden part of the psyche. Pettit’s paintings examine the lingering impact of her rapist’s denial, her internalized persecution and her renewed understanding of her profound lack of culpability as a child.

In What Will I Find the artist – suspended in water – turns to face a pair of tiny eyes illumined in the darkness, symbolizing a previously suppressed part of her trauma coming into focus. Child shows the naked adult artist standing in a youthful pose, representing her new perspective on the earlier, castigated part of herself. ‘You experience some grief when you realize how much you blame yourself, and how present you are in your own victimization,’ she says. ‘As a child, you cannot validate yourself. You take the lack of validation – or the blame that happened at the time – and it lives with you, shaping every perspective you have as you get older.’ These works confront suffocating narratives of idealized victimhood while lovingly reconnecting Pettit with repressed parts of herself.

Pettit is not the only artist in recent years to challenge the deeply entrenched model of the passive ‘perfect victim’. Laia Abril’s expansive project ‘On Rape’ (2020) was informed by the 2016 ‘wolf pack’ gang rape of an 18-year-old woman in Spain. In this case the perpetrators were charged with the lesser offence of ‘sexual abuse’ due to a lack of evidence of violence; filmed footage showed the woman frozen, with her eyes closed, which the defense argued was proof of consent. This case led to Spain’s own #MeToo movement and inspired Abril’s inquiry into the gender-based stereotypes and myths that perpetuate rape culture and fuel victim blaming.

‘On Rape’ has been published in book form by Dewi Lewis, with selections from the research project exhibited at institutions such as C/O Berlin (2024) and Foam in Amsterdam (2021). The project includes outfits worn by survivors, such as a nun’s habit, a US army uniform and a white wedding dress. ‘The outfits do not solely represent individual survivors; symbolically, they embody the very institutions that failed them, as well as the millions of survivors before and after them,’ says Abril. ‘These are the same structures of rape culture that not only failed to prevent the assaults but often created conditions that enabled them. And when survivors attempted to speak out, they were frequently silenced, dismissed or disbelieved.’

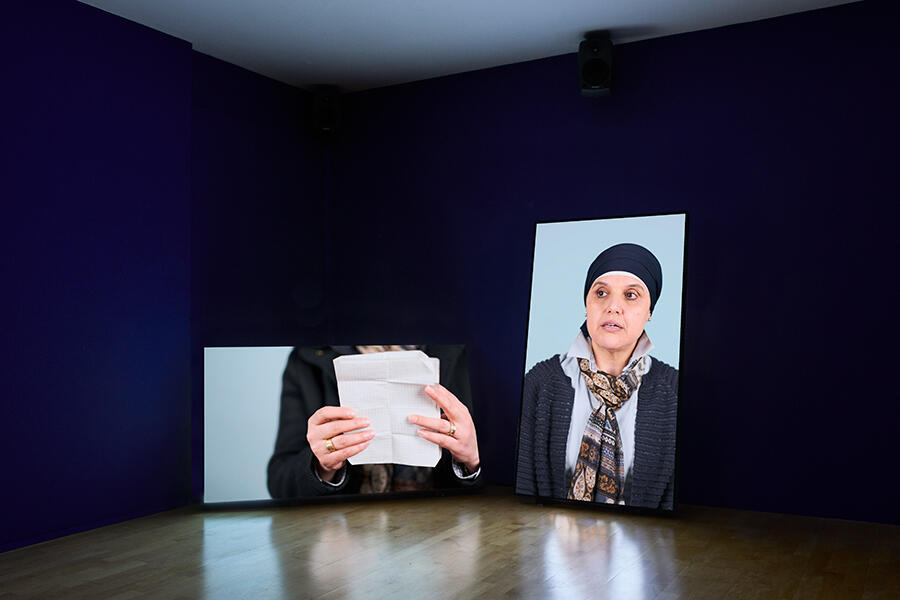

Gabrielle Goliath’s series ‘Personal Accounts’ (2024–ongoing) similarly confronts the colonial and patriarchal structures that enable mass violence. The South African artist’s videos present personal accounts of survivors in Johannesburg, Tunisia, Milan and beyond. In these works words are withheld, leaving only the sounds in between – inhalations, murmurs and throat clears – highlighting how believability is often unfairly tethered to verbal testimony. While many of Goliath’s collaborators have experienced sexual violence, the project also addresses racial and systemic violence, and the entanglement that connects all three.

‘South Africa contends with particularly high levels of rape culture, but I am very careful to frame that,’ she tells me. ‘What are the historical conditions that make this possible? You go to the archive and there is no account of rape, of sexual violence.’ She points to imperialism and slavery as the origin of this silence. The project focuses on her collaborators’ lives now; this, she says, is ‘not a work of violence, but a work of survival’. Changing the ingrained systems of victim blaming, Goliath asserts, means ‘dismantling the white, patriarchal structures and world order that make Black, trans, femme, Indigenous lives far more precarious and vulnerable to violence, disposability, not being believed’.

Crucially, her collaborators choose how much to share. Filmed in a private studio with the artist and a videographer, some talk about their experiences in detail, while others may share a poem or a recipe. Collaborators can choose to have their testimony translated for Goliath or speak in their native language, with the artist never knowing the content. ‘What happens when these individuals are given the opportunity to withhold, to not disclose and choose to not subject themselves to a place in which their voices are so easily not heard – or, if heard, easily discredited and not believed?’ she asks. ‘In that choice, there is a refusal to let that be the defining factor of their subjecthood.’

Works such as Goliath’s offer an alternative to the performative, confessional or legal models that dominate the court’s and media’s language around sexual violence and victimhood. The focus shifts to the act of being seen and held, rather than the specific articulation of words or feelings – expressions subject to patriarchal value judgements. ‘It’s not easy work, but “Personal Accounts” put in place conditions that make the individuals feel secure and able to speak,’ she says. ‘I’m not saying it’s only unspeakable, unrepresentable. But let’s find those words.’

Main image: Lydia Pettit, Mercy (detail), 2022, oil on canvas, 2 × 1.7 m. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Judin, Berlin; photograph: Elliott Mickleburgh