How Candice Carty-Williams Uses Black British English to Tell Caribbean Stories

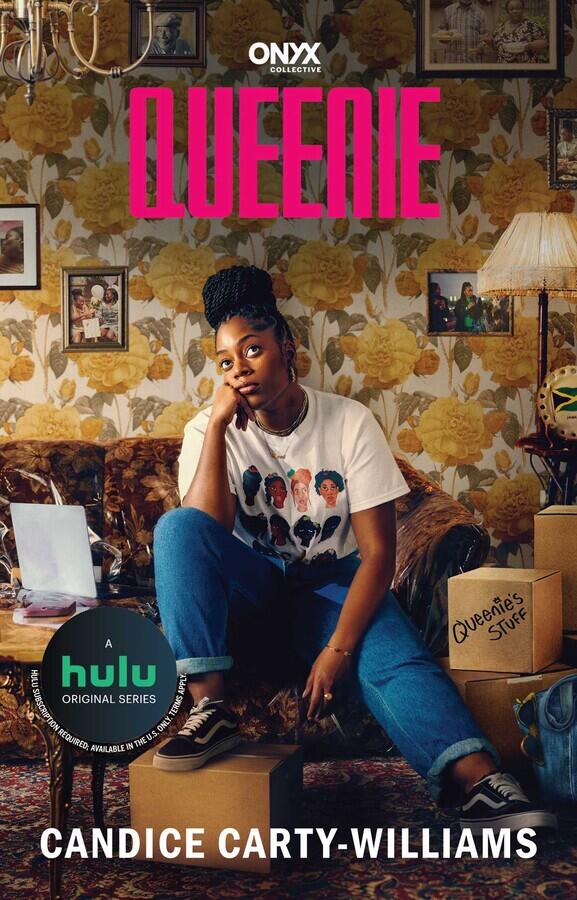

The author of Queenie (2019) discusses reclaiming voice, honouring her aunt’s memory and resisting white literary tradition

The author of Queenie (2019) discusses reclaiming voice, honouring her aunt’s memory and resisting white literary tradition

On the occasion of her first public reading in the Caribbean, the British-Jamaican author Candice Carty-Williams spoke with Rianna Jade Parker at Calabash International Literary Festival in Jamaica about her approach to memory, the significance of emotional language and writing in her first dialect, Black British English.

Rianna Jade Parker Your presence in this year’s edition of Calabash was apt and duly acknowledged on stage by Jamaican-American actress Sheryl Lee Ralph, who was also a guest speaker. We listened to you read from your new essay, ‘Memory as Fiction’, honouring the wisdom of your Auntie Susie who you’ve been able to immortalize in your fiction. How was your experience reading to a largely Caribbean audience and in the region itself, at one of the most coveted platforms in the literary world?

Candice Carty-Williams I’d been lucky enough to be in the audience for previous talks that day and the night before and immersing myself in the crowd helped me to realize how gentle and receptive they were. I’m still processing how rare it is, as an author born to Caribbean parents and forced to live in the UK, to have Jamaicans in front of me and the Atlantic behind me. In terms of what I was reading – an essay about my late aunt, grief and the contortion of my memories of her – I knew that I’d probably choke, might not be able to get through it, would have a lump in my throat at the very least, so I asked the audience not to make any noises of encouragement if any of the above happened. Beautifully, they obliged and were so kind to me when it was over. I definitely felt at home, both in myself and in front of them.

RJP What Caribbean or Black British literature, if any, has informed your reading and writing?

CCW I try to stay away from fiction when I’m writing, and so it’s my great joy to get back into it when I’ve handed a draft of a script or a novel in. While I’m writing, it helps to know the rich Caribbean space that I’m writing into. Some of the books that have stuck with me are the short story collection How to Love a Jamaican (2018) by Alexia Arthurs; anything by Courttia Newland but specifically The Scholar (1997); anything I can get my hands on by Leone Ross; and Here Comes the Sun (2016) by Nicole Dennis-Benn is one of my favourite novels of all time. Frying Plantain (2019) by Zalika Reid-Benta is another favourite of mine. I loved When We Were Birds (2022) by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo; and The God of Good Looks (2023) by Breanne McIvor. What I don’t want anyone to sleep on is the Jamaican literature section at Norman Manley International Airport in Kingston – I’ve found some of my favourite reads there from independent Caribbean presses.

RJP The historical and contemporary gaps in Black British literature, means that the through line in Black British writing is less obvious, especially when compared to other cultures. In 1978, Black Ink Collective founded their publishing house and a new Black writers’ collective. We’ve had pockets of activity rather than one consistent tradition; so far there’s no one occasion and there’s no through line. I think that’s quite hard, from what I understand. It feels like things happen in a cipher. These days, I think it’s more individual conversations rather than collective thought. As an author, we long for a nostalgia that we weren’t part of, but I think that we can have it again, right? I always answer questions – DM me! That’s why I do those Q&As on Instagram so regularly, so that people can ask me about the industry, about my work, about process in general.

RJP We can now easily identify a dialect of Black British English (BBE) that is primarily informed by Jamaican Patwa, wider Caribbean creole and more recently West African pidgin. BBE is young and varies from city to city. In what language do you think and write in?

CCW South London Vernacular. I wish I could think and speak in another language, but I’ve got Patwa and I’ve got South London. I will never try to think or speak in a different way. I’m not someone who’s going to spend an hour trying to describe curtains, but what I will do is spend time quite effortlessly feeling through someone’s emotions and crying through that if I need to when I’m writing. That’s really important to me. The main language I speak is emotion.

RJP What kind of cultural criticism do you think is actually useful for both the author and the readers?

CCW That’s an interesting question in the context of writing as a British-Jamaican author based in the UK. Because I, and those like me, are always traversing cultures. Aren’t we all traversing cultures these days? I also feel like we’re having to make a distinction between online culture and real-life culture. To me, cultural criticism as a whole plays a part simply through its existence. It’s a reminder that everything created holds space and can and should be interpreted and analyzed through multiple lenses, handed over to the critic once complete.

RJP With your next book, what can readers anticipate?

CCW Throughout my writing career, I’ve only ever wanted to write – or make shows – about the parts of life that concern or interest me. In my mid-twenties, I explored how hostile the world can be to a Black woman of the same age, especially one grappling with the trauma of a lack of maternal love. My television show Champion (2023) examined the music industry’s baffling misogyny and exploitation, and how those dynamics could sow division within a Jamaican family. In People Person (2022), my second novel, I shifted focus from emotionally unavailable mothers to emotionally and physically absent fathers, and the lasting imprint of the father wound on five siblings. Now in my thirties, this new novel follows a character confronting what it means to be raised with the belief that motherhood is the ultimate aspiration – while simultaneously facing the reality that it might not be part of her future. And of course, all of this is filtered through the lens of a Black woman living and working in a present-day London that remains as hostile as ever. Add medical racism into the mix, and you’ve got yourself a party. I’m sure I’ll deal with marriage next.

Main image: Candice Carty-Williams at the Calabash Literary Festival 2025. Photograph: Justine Henzell