Jessica Vaughn Showcases White-Collar Failure

At David Peter Francis, New York, the artist repurposes medical impairment charts and losing lottery tickets to address inequality at the office

At David Peter Francis, New York, the artist repurposes medical impairment charts and losing lottery tickets to address inequality at the office

New York was under a heat dome when Jessica Vaughn’s ‘Cognitive Fatigue’ opened at David Peter Francis, but the atmosphere inside the gallery was steely and cold. The cubicle partitions, government reports and losing lotto tickets that are Vaughn’s material invoke the detached bleakness of office life; a digital thermometer in Building Comfort (2025) displays an uncomfortably cool reading of 50 degrees Fahrenheit (10 degrees Celsius). Conceptually scattered and, at times, elusive, the seemingly disparate works engage with concerns the artist addressed more pointedly with earlier projects, mostly around the racial inequities and failed promises of white-collar labour.

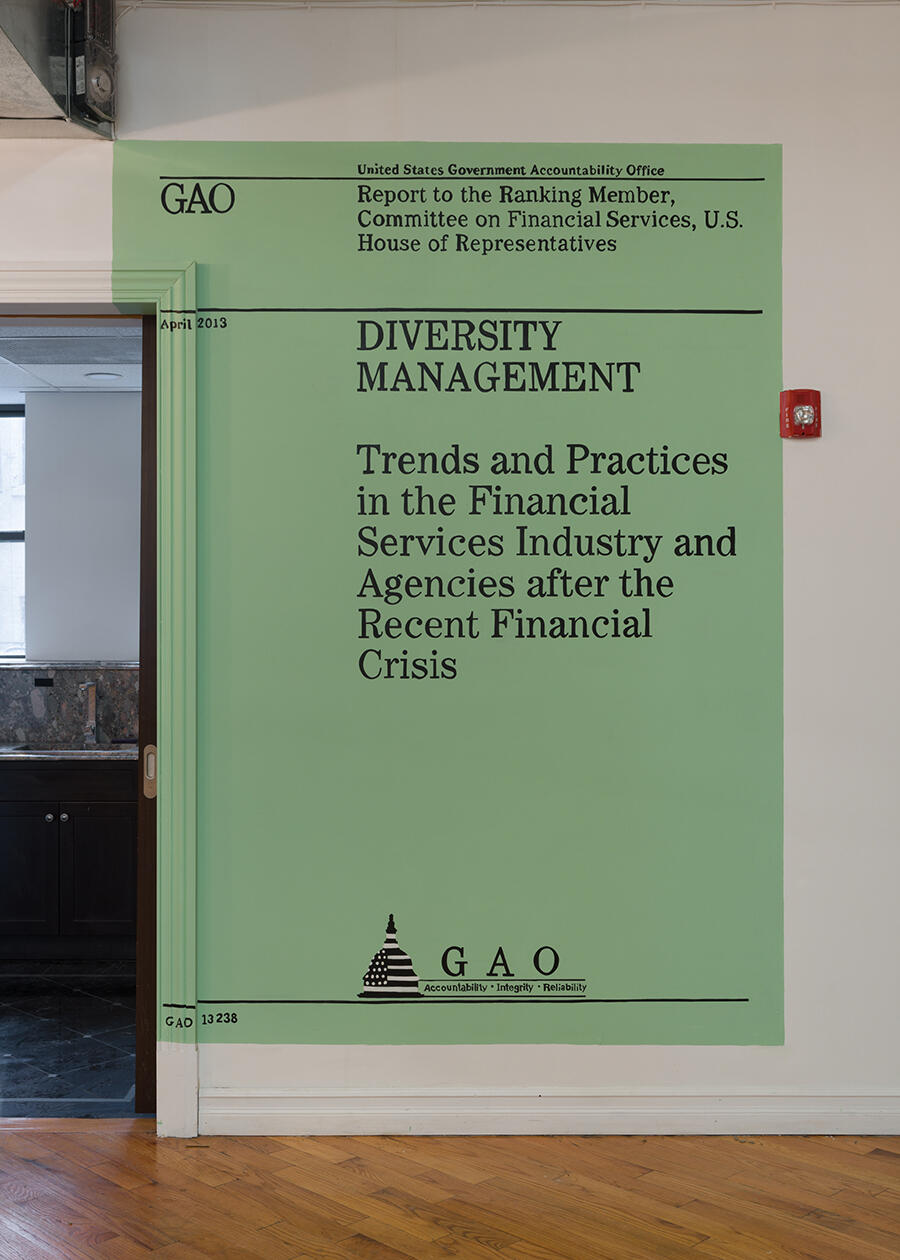

A hand-painted mural in the lobby outside the gallery, Problem Sets (2025), replicates and enlarges the cover of a ‘Diversity Management’ report conducted by the Government Accountability Office, a federal oversight agency currently (predictably) under threat as US President Donald Trump dismantles initiatives for diversity, equity and inclusion. Yet, by only reproducing the cover of the report and restricting access to accompanying rooftop murals (only viewable via live-streamed surveillance footage), Vaughn seems to hint that such efforts have always been hollow, a kind of diversity aesthetics more focused on fulfilling quotas than altering structures.

The modular office architecture that Vaughn employs was popularized in the late 1960s, not long after affirmative action was implemented in the US. Cubicles theoretically made workspaces more egalitarian (maybe even inclusive), giving employees a semblance of the personal space usually reserved for executives. But their homogenizing uniformity and adaptability imply that those employees are as interchangeable as the boxes that contain them.

The stained, drearily upholstered cubicle walls of the kind that Vaughn previously assembled into labyrinthian installations under the title Depreciating Assets: Avenir Series (2019) are here mostly stacked in listless piles that evoke a deserted office. Two freestanding configurations, though, interact with the gallery’s architecture and remind viewers that this, too, is a workspace. In one case, an obstinate, solitary panel blocks the sliding door to the gallery’s office from fully closing: a subtle intervention indicating that the art on display cannot be fully extricated from the realities of administration and labour.

Atop a makeshift pedestal of three recumbent partitions is Plenum (2025), a spirometer – used by medical professionals to measure a patient’s respiratory strength – connected to a concealed air compressor. The contraption regularly emits a mechanical wheeze that just barely levitates a plastic yellow ball: a feeble sign of (artificial) life among the corporate ruins. Draped over the other mound is Cinch Manufacturing Co (TRW) Union Steward (2025), a sheet of paper-white chiffon printed with a snapshot of Randolph and Martha Jarmon, two Black warehouse and factory workers, who, according to the caption, ‘enjoy their time together outside of the workplace’. Despite the stilted caption, the photograph looks as if it were plucked from a family album. But what does it mean that the only image of people amongst these trappings of white-collar offices is, incongruously, of blue-collar workers?

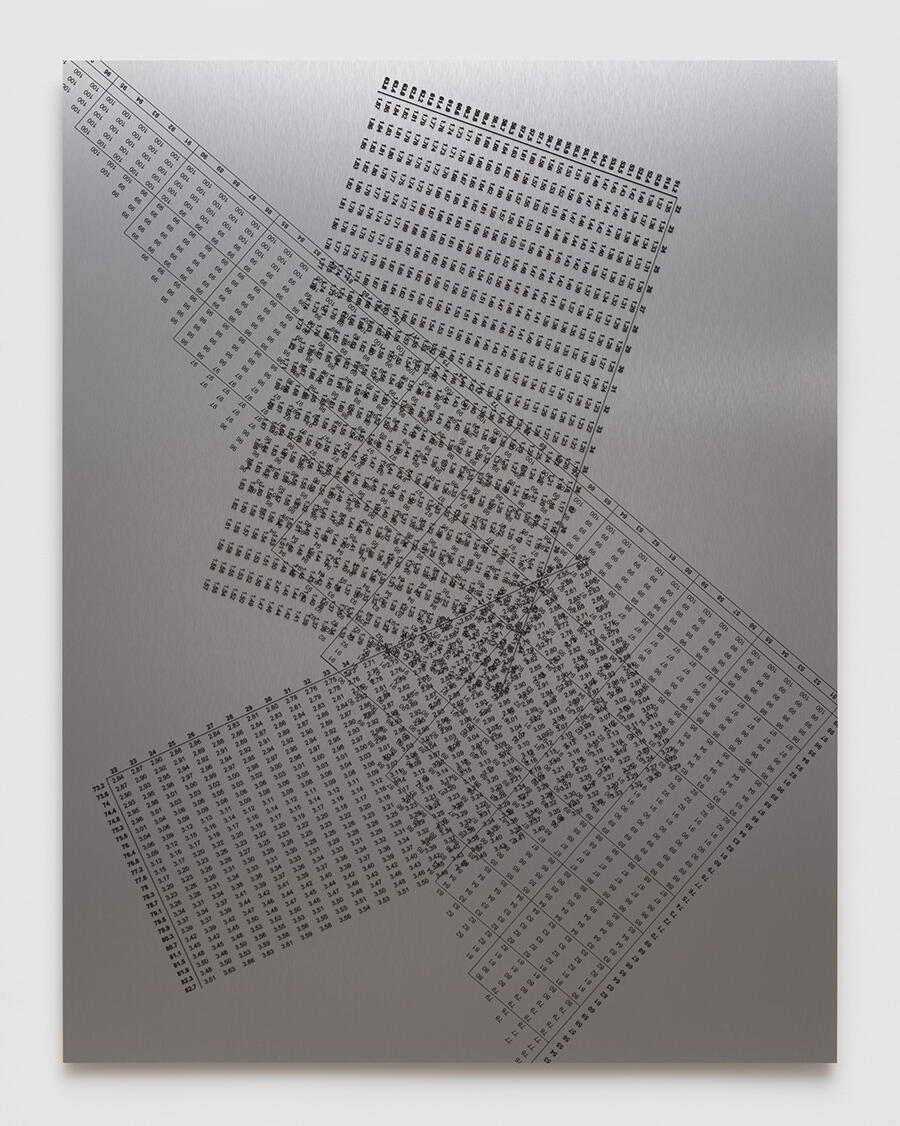

Vaughn’s references to workers are mainly made indirectly, through cartoons, diagrams and statistics. Two nearly artless prints on brushed aluminium feature grids of unlabelled numbers from ‘whole person’ medical impairment charts quantifying what constitutes an ‘unimpaired’ employee for the purposes of workers’ compensation. In ‘We Are Not Servants. We Are Not Machines’ (Combined Impairment Values Charts) (2025), for example, multiple tables overlap in a constructivist composition that further muddles the dehumanizing data, rendering it even more abstract and useless. Meanwhile, the scratched-off, ripped-up lotto tickets scattered across $587 Stoppages (2025) conjure dashed dreams of escaping the working life with the perfectly random combination of numbers. Throughout Vaughn’s exhibition, as in the world at large, human figures are replaced by numbers, figures of another kind, data points in a broader, dispiriting accounting.

Jessica Vaughn’s ‘Cognitive Fatigue’ is on view at David Peter Francis, New York until 26 July

Main image: Jessica Vaughn, $587 Stoppages (detail), 2025, discarded lotto tickets on dibond panel, vinyl paint,1.5 × 2.1 m. Courtesy: © Jessica Vaughn and David Peter Francis, New York