Surfing on Acid

With her Whitechapel show opening today in London, Mary Heilmann talks about studying in California, ‘home arts’ and surfing

With her Whitechapel show opening today in London, Mary Heilmann talks about studying in California, ‘home arts’ and surfing

Amy Sherlock You started out as a ceramicist.

Mary Heilmann In 1959 I was an undergraduate at Santa Barbara, which was famous for being a surfing school. That’s why I originally went there (not to surf; to watch the surfers!), but then it turned out they had a really good English Literature department, so I decided to major in that and I took up throwing pots as a hobby. There was a whole scene at that time. We were all late beatniks and early hippies, throwing pots and drinking tea out of handmade bowls.

In 1963 I went to Berkeley to study with Peter Voulkos, a great ceramicist and a radical teacher. He would throw a great big pot on one of the early electric potters wheels, walk across the room in his pointed Beatles boots, trip, dropping the whole thing on the floor, and then pick it up and squeeze it into a sculpture. He saw it as a performance or a dance.

AS Tell me how you then came to painting, or how painting came to you?

MH At Berkeley I was influenced by Bruce Nauman, who was doing radical work, and that meant I had a hard time because the teachers were all rather conservative. At one point they actually wanted to kick me out of the school! Not Voulkos, but other ones. They didn’t like Voulkos too much either, actually.

AS Why did they want to kick you out?

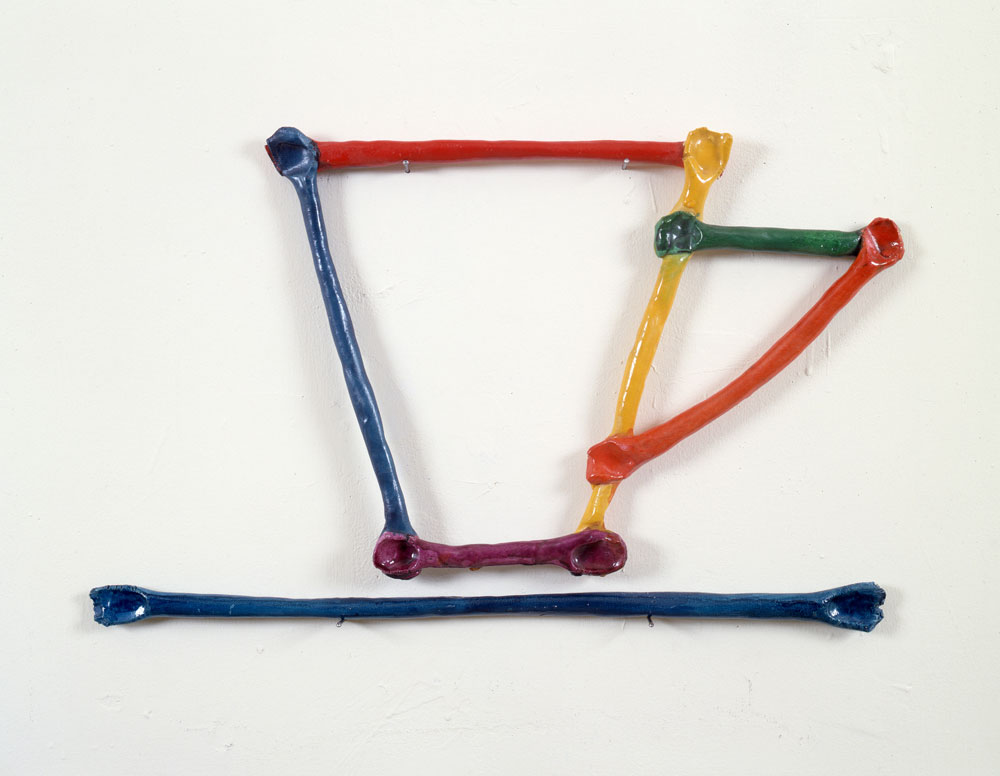

MH Because I would make sculptures leaning against the wall, I’d use flocking on surfaces, I’d make fibreglass lumpy things… It wasn’t the traditional kind of aesthetic that they were used to dealing with.

So I went up to the University of California, Davis, to study with William T. Wiley – Bruce was studying with him too. We talked about Duchamp, – a lot – and I really got a lot out of that, knowing that the new kind of edgy art was actually good.

AS Why did you move from there to New York?

MH When we were at Berkeley we spent a lot of time going down to look at the art scene in Los Angeles. Ferus Gallery was a big part of that, Irving Blum and Kenny Price were showing already; there was just a lot of really good art being produced down there. I wanted to move there, but I could tell that I wouldn’t be able to make a go of it there what with LA being so big. And then also: all guys.

AS At that time LA did have this reputation for having been a bit of a boys club – especially the Ferus crew.

MH A boys town! So I got smart and moved to New York. It was great scene – and there were actually women there! Of course it was hard to get in with the gang there, it was very cliquey, but it was mainly hard for new guys who showed up.

Gordon Matta-Clark was a friend of mine, and when he arrived a few years after me, being super social and talkative and energetic and attractive, he would go in and just start talking to the guys. Even still, he couldn’t make a dent! Later on, when they started seeing his art, it all worked out.

Everyone hated painting – including me – but I would always say ‘I’m a painter’ so that we’d get into big arguments about it.

AS Who did you fall in with when you arrived?

MH Keith Sonnier was one of the first, then Richard Serra, and Eva Hesse was big. I saw her but never met her. I knew all about her because everyone was always talking about the work. Lee Lozano was working there as well.

AS And you were making work while you were there?

MH I kept working and I got to show, but not in the big mainstream galleries. When I moved I thought I was really going to be big and popular as a sculptor. I was not. [Laughs]

Back then the big thing was to have conversations, to talk theory, at least what was theory way back then – one of my favourite people to talk to, or to listen to, was Robert Smithson. When I couldn’t get anyone to take an interest in my sculptures, I decided to call them paintings, because a lot of the pieces were flat on the wall. Everyone hated painting – including me – but I would always say ‘I’m a painter’ so that we’d get into big arguments about it.

I said that I was a painter and that David Hockney was my teacher at Berkeley – he was, that was true. David came up to Berkeley from Los Angeles when he was only a couple of years older than we were but he already had a reputation from appearing in magazines. The painting department was very conservative and the students weren’t too interested in him, so all of us, all of us allegedly ‘radical’ sculptors, decided to take the class instead!

AS That’s interesting, because there are definitely resonances between some of your works and his – in terms of the palette more than the subject matter.

MH He was a huge influence, and he was really advanced in his thinking about exactly what art meant. He would put a little squiggly line on the face of a painting to show the reflection of the glass – the alleged glass – in the frame.

AS How realistic are your paintings? While they are by and large ‘abstract’ they sometimes seem to allude to natural forms – waves, hills.

MH Sometimes there will be some actual imagery in there and sometimes they will need the title for the reference, but they always have a real backstory.

AS Your titles can be quite … funny? Surfing on Acid (2005), is a notable one.

MH Surfing on Acid is a famous one – that got some attention. But that’s the wonderful thing: you look at the work, you read the title, and you think about it.

AS Surfing on Acid feels very rural, natural, whereas other titles seem much more urban. Maybe that reflects your two different poles of reference?

MH That’s right: city and nature.

AS Have you ever wanted to go back to LA?

MH There was a time in the early ‘90s when nothing was happening between me and the art world – there was a big economic crash right around that time, and my gallerist Pat Hearn was having a hard time, business-wise. I was very inspired by what was going on in what came to be known as Silicon Valley, and so when a job opening came up at Stanford, I thought I should try and get it. I thought I’d be right in the middle of that digital culture.

AS Do you think that interest in the digital plays out in your work?

MH I think so. Partly, it’s just the idea of different kinds of mathematical combinations playing out against each other. I was never really a smart cybernetic head, but thinking about numbers has been a big part of my life, ever since I was little.

AS Can we talk about the title for your Whitechapel show, ‘Looking at Pictures’? It’s also the title of the collection of Robert Walser’s writing on art that was published at the end of last year. It’s a lovely book: it’s almost a series of stories about what’s happening in various pictures. Are there always narratives running through your paintings?

MH Yes, and sometimes only I know it. A lot of my studio time is spent sitting, thinking, looking, and often trying to figure out the easiest way to try and do something. Rather than working all day, I think all day. Spending this contemplative time in the studio is almost like spending time writing, and writing is a big part of my life.

I’m not a big surfer. I never was. But I really loved sitting on the beach and just looking at the guys, watching the geometry, the timing… It’s like a stage.

AS Can you tell me the story of your most recent painting?

MH There is one brand new painting in ‘Looking at Pictures’ called The Green Room – a surfing term for when you get inside the tube. It’s inspired by a book by William Finnegan called Barbarian Days, which is about his travels around the world. He’s a journalist dealing with really intense stuff – in war zones, covering the troubles in South Africa, for example – but wherever he is he manages to go surfing.

AS What is it about surfing that appeals?

MH I’m not a big surfer. I never was, not even as a kid. It’s hard, it’s a big commitment, and way back in San Francisco it was all guys. Even being a radical, aggressive feminist girl, being a surfer was hard, but I really loved sitting on the beach and just looking at the guys, watching the geometry, the timing… It’s like a stage. It’s a great culture.

AS Can you talk about your use of furniture and your domestically scaled ceramics?

MH I think of that work as ‘home arts’. I’m really interested in the influence of home décor on peoples’ experiences of art at every level of social class. It was a big part of my growing up: my mother was always rearranging the furniture in the living room, and looking at the paintings that she had in there was important. But I wanted to put chairs in my shows so people would sit down, stay longer, and talk to each other. It’s a kind of relational aesthetics.

I first put chairs in a show in the ’90s, and it was fabulous – I didn’t know this at the time, but they really relate to Donald Judd’s chairs. They were basic but they had wheels, and all of these young tourists would roll around the room and talk to each other. The experience of looking at art wasn’t just staring at art; it was looking at the art and then talking about it.

It’s funny because furniture has this big influence on you from the beginning of your life to the end, and you don’t even think about it consciously.

AS There’s something that comes up again and again when people describe your work. They say that it’s beautiful to look at, that it’s joyous and it captures emotion, but then there’s a tendency to qualify those descriptions with: ‘but there’s more there than meets the eye’. Frank Stella famously said: ‘What you see is what you see.’ Is that the case with your work?

MH No. There’s more going on there than what you see; it’s about the backstory. But what you see will always make you think of other things. In a way, it’s a dialogue.

AS Do you have any unrealized projects?

MH I’m constantly thinking of ideas for sound works that could sit alongside my pieces. They wouldn’t be musical sounds, but conversations overheard on the subway and then mixed in a non-linear way. That is a good idea, actually. I should probably do it and not just talk about it.

Born in San Francisco in 1940, Mary Heilmann studied literature at University of California at Santa Barbara from 1959 – 62, poetry and ceramics at San Francisco State University in 1963 and ceramics and sculpture at University of California at Berkeley from 1963 – 1967. She moved to New York in 1968 where she lives and works.

Mary Heilmann’s solo exhibition ‘Looking at Pictures’ opens at the Whitechapel Gallery today and runs until 21 August.