31 Women

Breese Little, London, UK

Breese Little, London, UK

‘31 Women’ pays homage to a 1943 exhibition of the same title at Peggy Guggenheim’s New York gallery, Art of This Century. For gallerists Josephine Breese and Henry Little, revisiting ‘31 Women’ is a way to explore the legacy of British modernist painting, starting with surrealism and the transition to formalism, and moving through conceptual art and the yBAs to the present day. Part of the fun of invoking Guggenheim’s legacy is toying with the myths and rumours that proliferate in the wake of her artistic and curatorial juggernaut. In addition to being significant as an early instance of an all-women show, the original ‘31 Women’ has a place in the chronicle of modernist extra-marital affairs for its part in the break-up of Guggenheim’s marriage to Max Ernst. In his official role as advisor for Art of This Century, he visited the painter Dorothea Tanning’s studio on a recce for a show that was to have been called ‘30 Women’. During his visit Ernst gave Tanning the title for her self-portrait Birthday (1942), played chess with her and promptly fell in love, moving in to her apartment within a week. Guggenheim later quipped that she wished she’d kept the number of artists to 30.

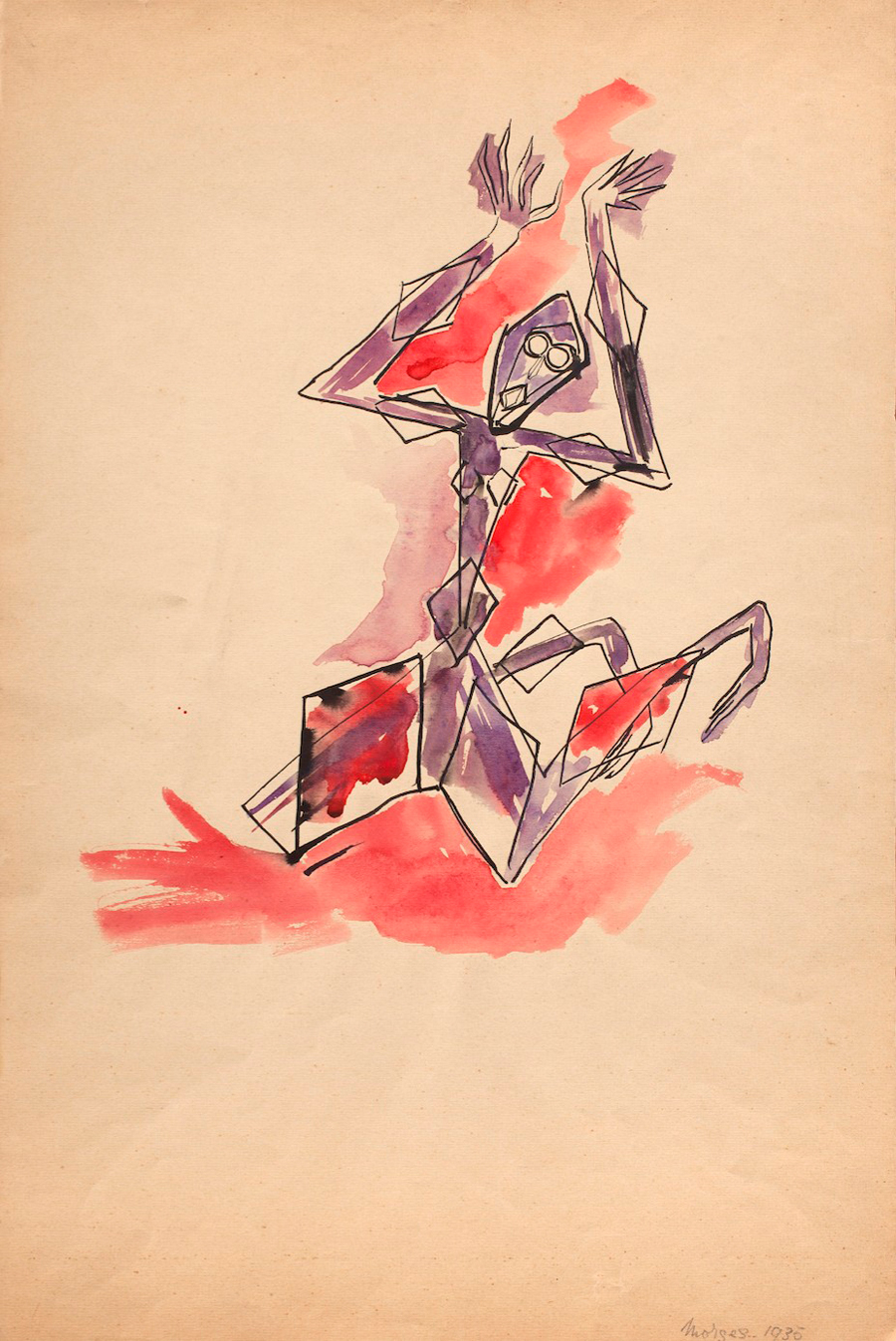

Breese Little’s show of 31 women, mostly painters, includes the work of artists in Guggenheim’s New York circle, notably: Eileen Agar, whose collage of a bashful Fighter Pilot (1940) proves that, in the right hands, a plain luggage tag and paper eyelets can be tenderly lifelike; and Catherine Yarrow, represented with Kneeling Purple Figure (Morges) (1935), an ink drawing of a hollow-eyed form captured mid-prostration, its diamond-shaped musculature daubed with a wash of unsettling red and purple.

The London exhibition is faithful to the tribalism of the original, staging intergenerational meeting points for works from the mid-1930s to the present day, all by artists connected with London. There are new works by younger London-based artist including Aimee Parrott, Mary Ramsden and Lauren Keeley, whose assemblage A Plate by Two Friends 1 (2017), made of laser-cut wood and screen-printed linen, seems both antique and ultra-modern. The exhibition runs in a line around the gallery, and much attention has been given to the formal, conceptual and affective apposition of works. Hanging Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Cover My Body In Love (1996) – a quintessential Eminesque hand-written letter with vivid descriptions of drunkenness, abortion, loneliness and penetration with an Orangina bottle – next to Helen Chadwick’s large polaroid Meat Abstract No. 8 Gold Ball / Steak (1989) suggests the influence of Chadwick’s work on younger artists, but it also stirs the carnal and the allegorical into a swirling miasma of female spunk.

Alison Turnbull’s framed triptych Orto Botanico (2011) features a list of typed descriptions and a grid of paint samples referencing colours in Rome’s botanical gardens. Turnbull’s work and a Bridget Riley gouache study on graph paper from 1972 flank Step (2007–08), by Rachel Whiteread, a diminutive stack of casts of the interior of cartons made in grey plaster and pink and orange resin that shares its translucence and tint with fruit-scented soaps from The Body Shop. It may span four decades, but this trio of works finds sympathy in the artists’ use of alluring colour.

In a 1978 interview, Guggenheim’s biographer Jacqueline B. Weld asked: ‘In terms of American painting, what was the role of your gallery?’ Guggenheim replied: ‘To give birth to it. I was the midwife.’ She failed to mention her role in giving life to a new kind of freedom, which would later gain popularity as ‘curating’, to bring out the meaning of art works through unconventional or strange juxtapositions. It’s an attitude Breese Little have evidently embraced in this tribute to the grandest dame of modern art.

Main image: 31 Women, 2017, installation view. Courtesy: Breese Little, London; photograph: Benjamin Westoby