Anya Berger (1923-2018)

‘The bearing of an aristocrat and the politics of a revolutionary’, Tom Overton pays tribute

‘The bearing of an aristocrat and the politics of a revolutionary’, Tom Overton pays tribute

Last year, this site published a profile in which I argued Anya Berger's work as a writer and translator had ‘shaped the horizons of the English-speaking left on issues of race, gender and class, and it's time this was recognized.’ For my own part, I wanted to recognize that her impact exists separately from that of her ex-partner, the writer and artist John Berger, whose biography I am writing. Anya's daughter Katya says that when she read her the piece in her care home, Anya nodded proudly at the catalogue of her achievements. But when it was suggested an injustice was being undone, Anya insisted ‘injustice is not there. The injustice lies in the fact that having been recognized didn’t do John much good, whereas my being ignored didn't do any harm to me.’ Among other things, I wonder if giving Anya her due credit is more important as part of a broader recent movement to recognize the labour of translators, not least because it has often been invisible work, often by women. Anya knew what she did, and that was enough for her, but it doesn't have to be enough for us.

On Friday 23 February 2018, she died peacefully in a care home in Geneva. Her last words were poetry, recited from memory in Russian and English – some Alexander Blok, Evgeny Yesenin, the first stanza of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin (1878), and particularly a song from Shakespeare's As You Like It (1603), ‘It was a lover and his lass’, with its refrain:

In springtime, the only pretty ring time,

When birds do sing, hey ding a ding, ding;

Sweet lovers love the spring.

In her memoir Somebody I Used to Know (2017), Wendy Mitchell compares dementia to the weather, clouding and clearing in patterns which are just out of control, not always predictable, and pointless to try to resist. By the time I first met Anya, she could barely speak any of the six languages she had known, and had little ability to recollect the life I was trying to write about at the time. But there seemed still to be a fiercely intelligent presence there, looking, as though from a distance, at her own faculties of memory and language as her daughter Katya and I asked her questions. When I was visiting my own grandmother, who was dying in a care home in Yorkshire around the same time, I can remember feeling her more or less present in the same way. I don't know if either would have approved of my slightly romantic impulse to call that presence a soul, so let's just call it a kind of sensual intelligence, and agree that it was there.

With Anya, that intelligence emerged when we went outside into the sunshine so Katya could blow cigarette smoke into her mouth – ‘bliss’, Anya would say – while we read her poetry from the anthologies kept at her bedside. Once, we'd not been getting far remembering her arrival in London as a Jewish schoolgirl refugee in 1939, and I found a bit of Autumn Journal, the long poem Louis MacNeice had written in that city in those months. In the unpublished memoir she dictated to her daughter Sonia, Anya remembers, not long after she arrived, asking to be taken to see the inspiration behind Wordsworth’s ‘Sonnet Composed Upon Westminster Bridge’ first thing in the morning. (Later in the memoir, she remembers having had a brief affair with one of the poet's descendants.) But it was Wordsworth's daffodils which stayed with her most – as Katya read lines to her, she could complete the rhymes. ‘Rhyme’, said Wordsworth's younger contemporary Arthur Henry Hallam, contains ‘a constant appeal to memory and hope’; it sets up an expectation, and reassures us when it arrives.

On one wall of her room, there was a 2016 drawing of a daffodil by John, with a line from the poem. Despite the acrimony of their break-up in the 1970s, there had been a reconciliation. In Confabulations (2016), he had written about these flower drawings and asked if natural forms can be looked at as messages:

texts from a language which has not been given to us to read … as I trace the text I physically identify with the thing I'm drawing and with the limitless, unknown mother tongue in which it is written.

Shakespeare is steadily conservative in politics; Wordsworth is the archetype of the young revolutionary who turns reactionary in old age. At first glance, both seem odd things to keep returning to for someone with Anya's political convictions: her translations are still the best or only English edition of various socialist classics. As we enter the 200th anniversary year of Marx's birth, her version of Ernst Fischer & Franz Marek's Marx in His Own Words (1970) seems a good one to pick out. Such a contradiction is not out of keeping with her character: the bearing of an aristocrat and the politics of a revolutionary.

On another wall of her room, there was a 1951 print of The Outing (La Partie de Campagne) by the unswervingly optimistic, Marxist artist Fernand Léger. Its figures are unpacking a picnic from a car, hanging their clothes on a tree, and relaxing in a landscape. ‘For all his repudiation of romanticism’, Peter de Francia wrote in a 1968 book which Anya proofed and corrected, ‘Léger created a particular kind of Arcadian landscape in his late pictures in which shrubs and trees, for which he had a particular affection, are a reassuring counterpart to iron grids and concrete armature.’ The potential of technology to create a different, freer future sits, without contradiction, alongside the potential of nature to renew.

The song Anya was whispering at the end is the only one by Shakespeare for which a setting – by the musician Thomas Morley – has definitely survived. Sung by two pageboys in the penultimate scene of As You Like It, it draws together the play's themes of exile, nature and politics and the instability of gender into a carpe diem motif: ‘And therefore take the present time’. Anya was remembering it just before Lent, the time the play was probably first performed; the time, in northern Europe, when the daffodils are coming out.

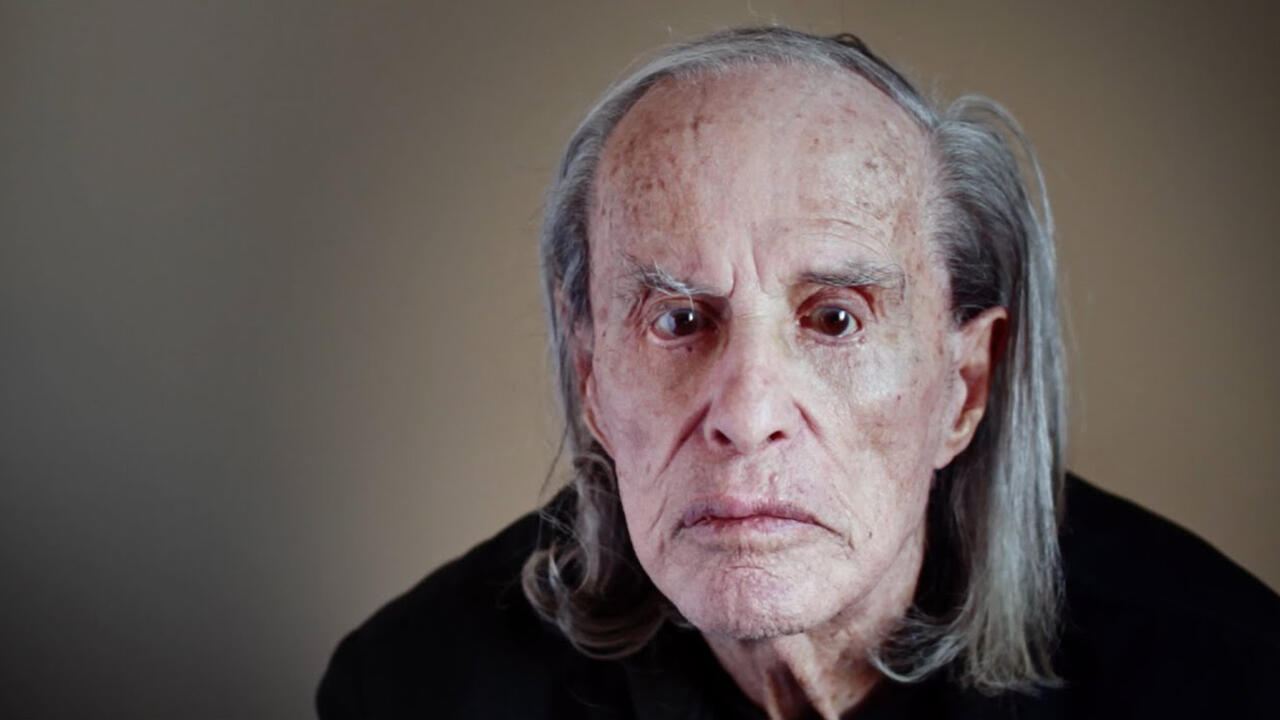

Main image: Anya Berger photographed in Italy. Courtesy: Anya Berger