Because The Night

How do representations of sleep reflect contemporary culture?

How do representations of sleep reflect contemporary culture?

‘We surrender to sleep, but in the way that the master entrusts himself to the slave who serves him.’

Maurice Blanchot, The Space of Literature (1955)

‘Sleep is surely one of the most puzzling of all human behaviours,’ declares neuroscientist Matthew Walker in the opening pages of Why We Sleep: The New Science of Sleep and Dreams (2017). ‘When you are asleep, you cannot gather food. You cannot socialize. You cannot find a mate and reproduce. Worse still, sleep leaves you vulnerable to predation […] Yet sleep has persisted.’ Walker’s bestseller attests to the persistence of a discipline that has generated both academic and popular curiosity at a time increasingly plagued by sleep deprivation and disorders. The sleep field received its most significant boost with the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, awarded for research on circadian rhythms. Developed by an American team of biologists – Jeffrey Hall, Michael Rosbach and Michael Young – the findings uncovered key facets of the body’s sleeping and waking clocks at the genetic level.

If these conclusions appear, at first glance, as somewhat self-evident – we intuit that daytime suits waking life and night-time encourages sleep – such common sense disregards sleep’s psychic and biological histories. In the article ‘Temporal niche expansion in mammals from a nocturnal ancestor after dinosaur extinction’ (2017) – published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution – a team of British and Israeli scientists claim that our earliest ancestors were nocturnal in origin and only reoriented to a diurnal regime following the extinction of the dinosaurs some 65 million years ago. Subsequent human sleep regimes have continued to vary widely, from the hunting clock of the pre-Neolithic tribesman to the seasonal calendar of the agrarian serf and the illuminated night crawl of the Edisonian boulevardier.

Appropriately, visual representations of sleep have existed nearly as long as recorded civilizations. One of the oldest extant examples is of a clay sculpture, discovered in Malta, known as The Sleeping Lady (c.3,000 BCE). Another, from Cyprus, is a terracotta totem depicting a mother cradling a sleeping baby (c.2,000 BCE). Both objects presage two motifs that have dominated Western art’s figurative representations of sleep since the Renaissance – the nude woman in repose and the nativity – as well as marking the domain of sleep itself as the purview of the feminine.

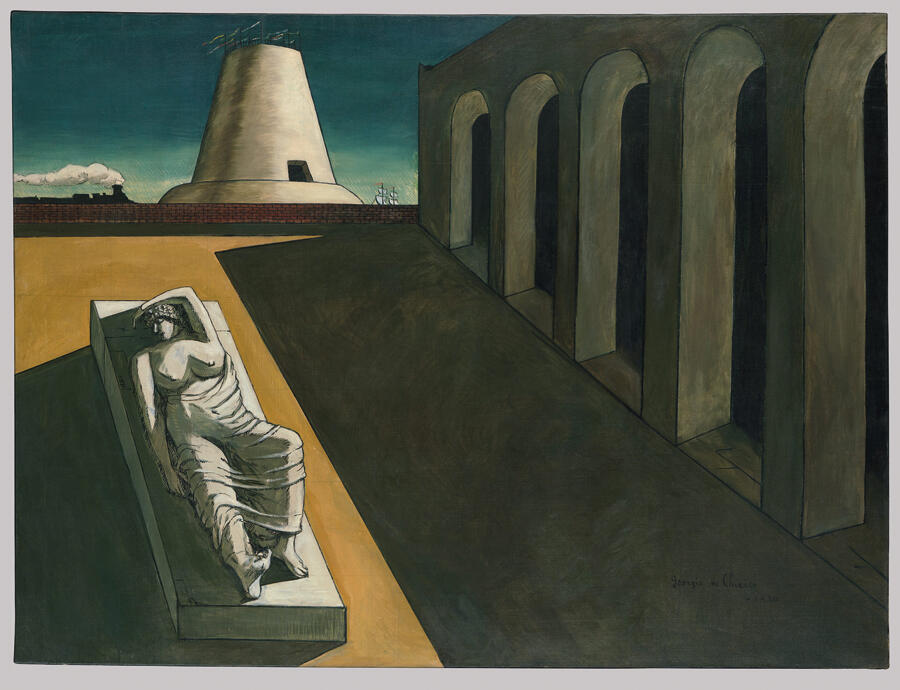

In the modern tradition, most art-historical narratives of sleep were yoked to late-19th-century romanticism and the early surrealist movement. Their championing of abstract forms (for example, in the paintings of Odilon Redon, J.M.W. Turner and James McNeill Whistler) and symbolic archetypes (in the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst and Félicien Rops) became the pictorial corollaries to literary meditations on dreams popularized by psychoanalysis. Texts such as Friedrich Nietzsche’s Die Geburt der Tragödie (The Birth of Tragedy, 1872), Sigmund Freud’s Die Traumdeutung (The Interpretation of Dreams, 1899) and Henri Bergson’s Le Rêve (The World of Dreams, 1901) conform to John Ruskin’s observation in ‘The Mountain Glory’ (1862) that: ‘Great art may be properly so defined in the Art of Dreaming.’ But, in celebrating the possibilities of the dream state, these texts also depreciate the act of sleeping itself to a mere psychic incubator or a blank screen preserved by the dream, which would communicate significant meanings or desires across the gradient of consciousness. Freud himself writes in The Interpretation of Dreams: ‘I have had little occasion to deal with the problem of sleep, for that is essentially a problem of physiology.’ Likewise, Carl Jung’s career-long research into dream analysis and mythic archetypes emphasized the dream’s salutary benefits in waking life. In one of his earliest texts, Sigmund Freud: On Dreams (1901), Jung concurred with Freud’s claim that dreams were a mere facade and a ‘guardian of sleep’; however, he did not elaborate beyond Freud’s mechanistic verdict on sleep itself.

Sleep’s knotty relationship to the 20th century’s emergent technologies, and the subsequent popularity of futurist ideologies, may have contributed something to the fracture of these romantic and psychoanalytic assumptions. The sensorial ruptures produced by cinema, recorded music and early multimedia performance were all of a piece with the industries of high-speed transportation, telecommunication and electrical gridding: what art historian Jonathan Crary, echoing Karl Marx, refers to in his 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (2016) as ‘metamorphic’ and ‘alchemical instruments’ that began to alter ‘durational processes’ of consciousness. Such alterations challenged the secular-humanist origins of 19th-century psychologies like Freudianism, which pivoted on the scientific traditions of the rational, bourgeois subject.

These transformations, however, did not register in official surrealist doxa. When in the Manifeste du surréalisme (Surrealist Manifesto, 1924), André Breton asks: ‘When will we have sleeping logicians, sleeping philosophers? I would like to sleep, in order to surrender myself to the dreamers,’ his musings were still entranced by a romantic portrait of dreams. Writing in 2013 about Joseph Cornell’s experimental film Rose Hobart (1936), the theorist Michael Pigott takes great pains to distinguish between the late surrealist’s views on sleep and those of his French counterpart: ‘It was as much the poetry of sleep that attracted Cornell, as it was the poetry of dream […] The banality of sleep, its literal and necessary everydayness, and the privileged and peculiar interiority and subjectivity afforded by the sleep state.’1 Cornell, who became acquainted with the Russian prima ballerina Tamara Toumanova in the early 1940s, was particularly inspired by her role as Princess Aurora in ‘Aurora’s Wedding’ (1922), Sergei Diaghilev’s one-act divertissement of The Sleeping Beauty (1890), which served as a backdrop or motif in many of the artist’s boxes. Cornell often explored sleep’s temporal or nostalgic pleasures through a mutual passion for gadgetry and bricolage, using the avant-garde formats of the assemblage film and shadow box. His work also bears similarities to Marcel Duchamp’s various experiments; the French artist was a friend and central influence on Cornell. Duchamp’s Apolinère Enameled (1916, depicting a so-called impossible bed), Sculpture for Travelling (1917–18) and Étant donnés (Given, 1946–66) reference the modern complexities of sleep outside the panacea of dreams.

Subsequent, time-based experiments – such as Andy Warhol’s five-hour film Sleep (1963, originally screened as an installation with a La Monte Young soundtrack), Terry Riley’s ‘All Night Concert’ series (1967) and Chris Burden’s two-week-long Bed Piece (1972) – reproduced sleep in ‘real time’ with all of its incumbent mundanities and soporifics. These works were also conceptually indebted to fluxus happenings such as Ben Vautier’s Sculpture vivante (Living Sculpture, 1962), a storefront installation in which the artist worked, ate and slept in public view, and Yoko Ono’s widely reported Vietnam protest series, ‘Bed-In for Peace’ (1969).2 With the fluxus valorization of so-called concrete art – a term employed by founder George Maciunas to highlight mundane experiences and readymade objects over abstract or imitative works of art – the act of sleep was not merely analogized but literalized as an artistic gesture. Rather than mediating or representing the idyll of slumber by visual artefact, fluxus artists enacted the direct experience of sleep itself as a rarefied performance of everyday life.

The shift away from romanticism and toward a politics of the quotidian also acknowledged the affective estrangements associated with sleep (or lack thereof). Boredom, restlessness, fatigue – all were symptoms of a postwar ennui haunted by the trauma of global industrialization. Literary theorists Maurice Blanchot and Emmanuel Levinas, anticipating the late-20th-century turn to poststructuralism, rejected the notion of sleep either as a salutary psychological state or as the momentary death it had so often been compared to in the philosophical tradition. Instead, viewing it through a prism of mysticism, they described sleep as a threshold or limit positioned outside the ‘natural’ prescriptions of unconsciousness and night – where it becomes a precondition of consciousness itself. In such negative ontologies, even the very nucleus of sleep – the act of repose – is thrown into doubt. ‘The first night is welcoming,’ writes Blanchot in L’Espace littéraire (The Space of Literature, 1955). ‘We enter into the night and we rest there, sleeping and dying. But the other night does not welcome, does not open. In it, one is still outside.’ For Blanchot, the world of sleep does not belong to the sleeper – it is a suspension between life and death. It is an ‘other’, a border zone, a space that can be approached but never entered or fully traversed.

Installation works such as Claes Oldenburg’s Bedroom Ensemble (1963) and Edward Kienholz’s While Visions of Sugar Plums Danced in their Heads (1964) visualize something of Blanchot’s conceptual impasse. Both artists replace the sleeper with the architectures of sleep – denaturalized bedroom set pieces that frustrate any possible repose. Oldenburg’s geometric abstractions of domestic furniture are visually flawless but practically unusable, while Kienholz’s horrifying vision of domesticity transforms the site of the bed into a sexual encounter between an estranged husband and wife. Similarly, Bill Viola’s multimedia installation The Sleep of Reason (1988) – a titular reference to Francisco de Goya’s famous etching of a nightmare, El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, 1797–98) – envisions a domestic setting’s nighttime idyll interrupted by video projections of insomniac imagery with a strident soundtrack. Viola’s convulsive images, foreshadowing both the sensory torture techniques employed by the US military at Guantánamo Bay detention camp and the millennial omnipresence of electronic screens, portray the nightmare of sleep as sleep perennially deferred.

In the works of Sophie Calle and Julia Scher similar architectures of sleep evoke the more lurid themes of voyeurism and surveillance. For both artists, the roaming presence of cameras or recording devices inside the bedroom calls attention to the power of the mechanical gaze to reduce familiar objects and bodies to images and the ways in which the dissemination of these images depersonalizes the sleeper’s experience of refuge. Calle’s career-long fascination with hotel rooms and voyeurist imaginaries – from ‘Les Dormeurs’ (The Sleepers, 1979) and Suite Vénitienne (Venetian Suite, 1980/96) to L’Hotel (The Hotel, 1981) and Room (2011) – many of which are referenced in her recent retrospective ‘Beau doublé, Monsieur le marquis!’ (Beautiful Double, Mr Marquis!) at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature – fetishizes the sleeper through his or her literal or figurative absence.

In her series ‘Surveillance Beds’ (1994–2003), Scher employs voyeurism to explore a more interactive instantiation of technology’s creep into private (and unconscious) space. In Always There (1994), for instance, a network of video cameras and live monitor feeds craned over a narrow pink bed invites the prospective sleeper to record and then watch him or herself in the intimacy of repose – though where the archived video is stored or shared is in question. This simultaneous experience of self-gratification and public performance in the most private of spaces marks the viewer’s increasing internalization of surveillance as part of the first internet era. As with much of Scher’s work, the conflation of domesticity with scopophilia also complicates the fragile boundaries between empowerment and exploitation.

For Calle and Scher, the bed is also a space of feminist politics. Rather than maintaining the sanctity – and invisibility – of the bed as a site for domesticating sex, they bring it into public space and view. This act of recontextualization is echoed in comparable bed pieces by Louise Bourgeois (Femme Maison, Woman House, 1994); Tracey Emin (Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–95, 1995, and My Bed, 1998) and Cornelia Parker (The Maybe, 1995/2013).

Alongside the pioneering studies of sleep spotlighted in 2017 was the 40th anniversary republication of Ray Meddis’s landmark The Sleep Instinct (1977). A tendentious text among early sleep scientists, Meddis’s book claims that sleep, far from serving a regenerative function, is an environmental trait that protects animals during hours of high predation or hostile weather. Meddis offers the possibility of ‘nonsomnia’, a biological correction he foresees for the near future that could switch off the sleep instinct altogether.

While Meddis’s theory has been repudiated by most scientists, its vision of a sleepless (and highly productive) society continues to gain symbolic currency. Perhaps now, more than ever, sleep’s contested status is a nexus of competing discourses from the medical sciences, the social economy and the public imagination. But after a century of art having been influenced and interpreted by myriad doctrines of dream analysis and other cognitive psychologies, has contemporary art experienced its own conceptual fatigue in relation to sleep?

One approach that continues to foster pre-modern narratives of sleep is the so-called slow movement, which has encompassed various experiments in art, architecture, cooking and cinema since the early 2000s. Although Arden Reed’s critical history, Slow Art: The Experience of Looking, Sacred Images to James Turrell (2017), makes few explicit references to sleep as a central motif in slow art, artists such as Jim Findlay (Dream of the Red Chamber: A Performance for a Sleeping Audience, 2014) and filmmakers including Scott Barley and the collaborative duo Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor explore the expressive potential of semi- or un-conscious states.

Barley’s glacial meditation Sleep Has Her House (2017), screened throughout 2017 and at the EYE Filmmuseum in Amsterdam in January, is shot entirely on an iPhone, and mixes high-resolution digital and pictorialist imagery of ghostly landscapes with infrequent cuts or obtrusive camera movement. The film’s methodical use of long-shots and protracted dissolves produces an experience that is both soothing and discomforting for the contemporary movie-goer, weaned on a language of close-ups and jump-cuts. While Barley’s earlier films rarely extend beyond 20 minutes, Sleep was conceived as a four-hour installation that encourages viewers to sleep in front of the screen. Like Warhol’s earliest films on sleep, sex and eating, and the fluxus experiments before them, Sleep Has Her House uses a composite of new and old technologies to recalibrate the audience to a slower, more primeval clock of waking and sleeping life.

Commissioned by documenta 14, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel’s film somniloquies (2017) uses the sleep recordings of 1970s singer-songwriter Dion McGregor – originally released as The Dream World of Dion McGregor (1964) – to produce an audio-visual immersion into the sleep experience. Accompanying McGregor’s babbled routines and vignettes are distorted close-ups of unconscious bodies that writhe and twitch. The eerie montage of image and noise, at times synchronizing and at others falling out of phase, creates a hypnotic sensorium from an extended, perceptual twilight.

The slow movement is part and parcel of a larger trend towards neo-gothic representations of technologized bodies in contemporary art. Like its Victorian incarnation, millennial gothicism spotlights the psychic crises and breakdowns of contemporary society through an exploration of the bizarre, dysmorphic or sublime. Artists associated with this tag – from Jake and Dinos Chapman to Abigail Lane and Marnie Weber – often skewer the excesses of science, technology, religion or other normative discourses. Chief among these aggressions is the development of what neoliberalism and fu-turism critic Teresa Brennan calls ‘bioderegulation’. Brennan, whose research into the psychological and social disorders of late capitalism marks an important turning point in biopolitics, defines bioderegulation as the technologization and financialization of ‘human time’ – from sabbatical to sex and especially sleep – as productive labour.3 Transforming Meddis’s utopian vision of nonsomnia into a grotesque, neo-gothicism challenges the effects of bioderegulation by invoking pathological monsters – sleep walkers, insomniacs, opioid addicts and other psychogenic casualties.

Such imagery appears strikingly in the work of writer Chloe Aridjis and painter Vincent Desiderio. Aridjis’s Benjaminian descriptions of hypnagogic characters, who amble between urban and domestic reveries, personify the bewitching fatigue haunting the hyperreal empires of Europe. In both Book of Clouds (2009), her debut novel, and ‘Kopfkino’ (2013), her essay on insomnia, sleep acts as a sort of missing character who, like the sonambulist in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), impels her outsider-protagonists into the dark margins of urban space and culture. Denied the pleasures of unconsciousness, these insomniacs experience only dizzying phantasmagoria or tedium – the curse of Charles Baudelaire’s boulevardier. For Aridjis, sleep is a secretive, almost medieval, ritual whose omission from modernity makes of it a sickly landscape beneath which history’s fantastical architectures repose as if on a baroque curve. Her forthcoming novel, The Antikythera Mechanism, promises to mine the rich, oneiric territories of the author’s own biography. Similarly, Desiderio’s elaborate, (Lucian) Freudian portraits of sleepers trade between sublime extremes of tranquillity and abjection. His most celebrated work, the 24-foot-long Sleep (2008), assembles an orgy of naked bodies contorted in varying degrees of somnolence in a Dutch mannerist style. In the similarly panoramic Theseus (2016) – the centrepiece of Desiderio’s show at Marlborough Gallery, London, in January – dozens of nude figures arranged in geometric tessellations are tortured in their sleep by monstrous insects.

A comparable gothic thread runs through recent installation and environmental art dedicated to urban architectures of sleep and recovery. In 2005, for example, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s The House of Dreams, filled the Serpentine Galleries in London with a network of enclosed tombs and cubicles for tired visitors, creating a menacing, hybrid interior of funeral home, cathedral and sanatorium. Conversely, Frank and Patrik Riklin’s seasonal Null Stern Hotel (Zero Star Hotel, 2009–ongoing), a hotel bedroom installation, trades on the sublime idyll of the mountain-side: a recurrent motif from the gothic novels of Horace Walpole (The Castle of Otranto, 1764) to Ann Radcliffe (The Mysteries of Udolpho, 1794) and Bram Stoker (Dracula, 1897). The ‘hotel’ is simply a double bed, side lamps and bedside tables in the middle of a field, with a panoramic view of the Alps. Sleep has returned to the bosom of nature – at least for the night.

Main image: Chris Burden, Bed Piece, 1972, performance documentation. Courtesy: the artist and Gagosian, London © 2017 Chris Burden / licensed by The Chris Burden Estate, ARS, New York and DACS, London, 2018