Big Data’s Deal with the Devil

At the DeYoung, San Francisco, ‘Uncanny Valley’ deftly examines the consequences of our capitulation to AI

At the DeYoung, San Francisco, ‘Uncanny Valley’ deftly examines the consequences of our capitulation to AI

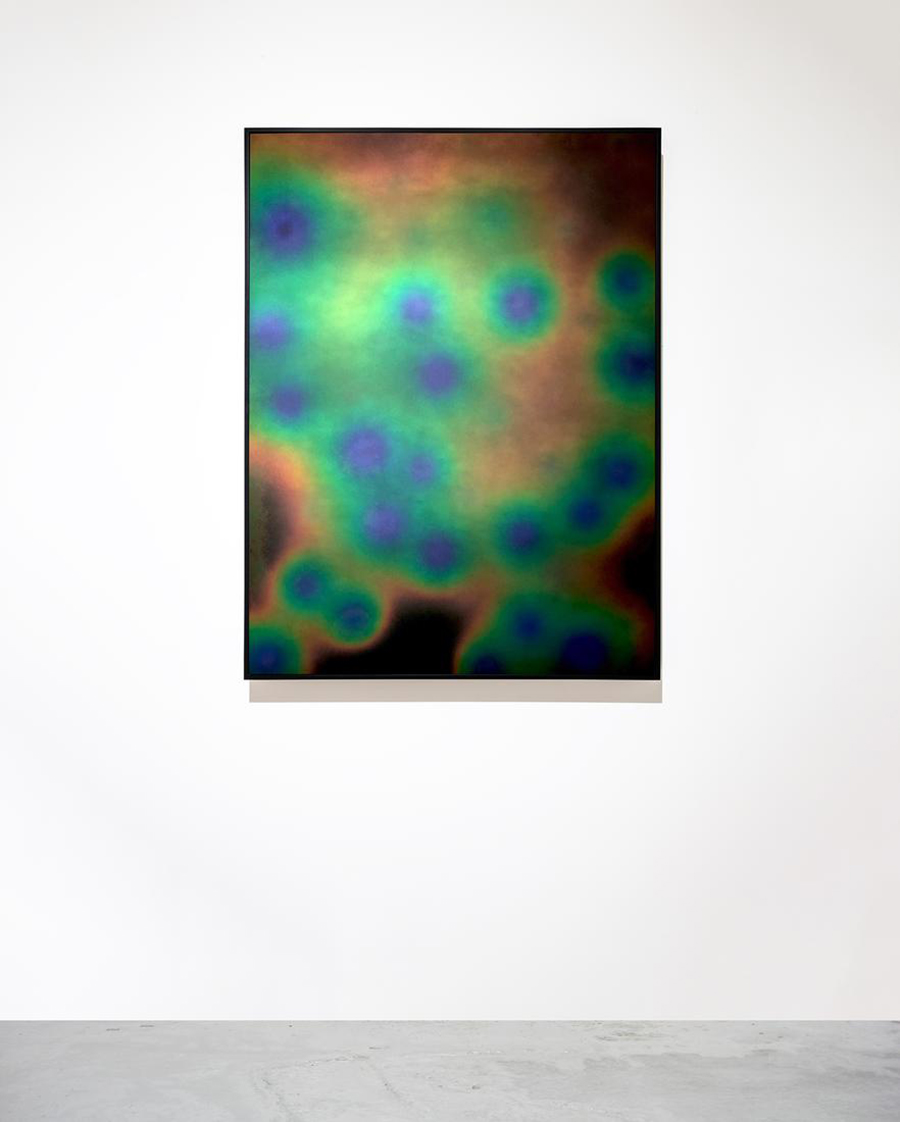

I keep thinking of Agnieszka Kurant’s liquid crystal paintings. I can’t help but wonder if their forms are still changing, their gasoline-rainbow palettes still mutating, or whether they’ve gone quiet like the rest of us. Kurant’s work sits in a central gallery of ‘Uncanny Valley’, the Bay Area’s first major exhibition to focus explicitly on how artists today are grappling with technologies that have – for the most part – come out of the region. The show’s title is a nod, of course, to nearby Silicon Valley – of which San Francisco has increasingly become an annex – but also reflects the show’s intent: to look not broadly at how technology has seeped into art, but at how the definition of what constitutes ‘humanness’ has been blurred by advancements in artificial intelligence and how artists are metabolizing these developments.

Kurant’s work – which, for me, was the soul of the exhibition – relies heavily on technology that reflects human emotions in real time. The aforementioned ‘paintings’, Conversions 1 and Conversions 2 (both 2019), consist of copper plates lacquered in liquid-crystal paint hooked up to a heat source whose output is modulated by an algorithm. This algorithm performs qualitative sentiment analysis that corresponds to actual human expressions – such as love, fear, anger, shock, revulsion, elation and sadness – harvested from the public social media accounts of activist organizations throughout the world. This data is fed into an ‘artificial-society’ model (a specific form of computer simulation used in social analysis) from which yet more information can be extracted. The social energy of thousands of people responding to world events is converted into thermal energy that manifests as colour and pattern: moods dictate to what degree the copper plates are warmed, with the resulting heat nudging the crystals to respond in an hallucinatorily vivid display. A particular expression of colour or form will never be replicated by this restless medium.

A principle challenge to any institutional exhibition aiming to tackle a field as changeable as tech is the subject’s evolving nature. Artists are not typically the first to get their hands on emerging technologies and, by the time they’ve succeeded in creating interesting work with them, their responses can often feel strangely outmoded. There is the occasional sense of obsolescence in ‘Uncanny Valley’ – after 82 minutes of Lawrence Lek’s animated film AIDOL (2019), for instance, I felt like I had logged onto Twitch and watched someone play a narratively incomprehensible, visually nostalgic video game – but, on the whole, I neither want, nor expect, artists to keep in step with advancements in technology, when such ‘progress’ already dictates so much of our lives.

Computer art of the 1960s and ’70s was, for the most part, an exploration of what machines could do aesthetically. Art that makes use of computers now tends to take advantage of their raw power, but employs older analogue technologies to give them form. All of the works in ‘Uncanny Valley’ employ AI, but are reified in familiar modalities – from Simon Denny’s sculpture of an Amazon worker cage, extrapolated from a patent filed in 2016 by the e-commerce behemoth (Amazon worker cage patent drawing as virtual King Island Brown Thornbill cage [US 9,280,157 B2: ‘System for transporting personnel within an active workspace’, 2016)], 2019), or Trevor Paglen’s wall montage of lustrous silver-gelatin portrait photographs, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead … (SD18) (2020), which draws from the American National Standards Institute database of mug shots. (Used to develop proto facial-recognition technology, the database is now the domain of social media.) A tangible polemics, however, might be the most unifying thread in the exhibition. The raison d’être of Forensic Architecture, for instance – one of whose members, Eyal Weizman, was denied entry to the US for the opening of the show on the basis of being a ‘security threat’ – is to hold abusers of power accountable using machine learning that enhances the capacity to investigate civil- and human-rights violations. Denny’s sculpture is as much a critique of the imperceptible environmental impact of technologies we use daily as it is a concretization of the inhumanity of the working environments that churn out the commodities we purchase in the atomized purlieus of e-commerce. Meanwhile, with her interactive multimedia installation, Lynn Hershman Leeson reveals just how much of our private information can be freely gleaned online. Shadow Stalker (2018–ongoing) invites visitors to enter their email addresses into an interface; the action triggers an internet search whose results appear within a human-shaped shadow projected onto the floor. Phone numbers, addresses, emails, CVs, bank account details, credit scores and more emerge: a sobering reminder of how little autonomy we have in a digital world.

The show’s selection of works is deft and its roster of artists populated by a number of veterans of the genre. They include (in addition to the above) Zach Blas, Ian Cheng, Stephanie Dinkins, Urs Fischer, Pierre Huyghe, Christopher Kulendran Thomas and Annika Kuhlmann, Hito Steyerl, Martine Syms and the Zairja Collective. I’m sure the exhibition’s curator, Claudia Schmuckli, is disappointed to see the show closed by the pandemic, but there may be no more apposite climate in which to explore the questions it raises. With the majority of the world’s population now living in isolation, the question of what makes us human when physical contact is forbidden feels more pressing than ever, especially as we lean increasingly heavily on machines to connect us and to serve as our surrogates in a virtual world. When ‘Uncanny Valley’ opened in February, the prevailing sentiment around tech was overwhelmingly negative; consumers had, quite reasonably in the face of election interference, lost faith in it. The pandemic, however, has forced consumers to re-engage and, in so doing, supply the tech giants with a fresh – and exponentially expanded – set of data points. Ticking the box is a deal with the devil: reap the benefits of the free service; pay with your private data. (It’s no wonder that data has surpassed oil as the most valuable resource on the planet.) In light of this, I suspect that, when we can finally visit museums again, ‘Uncanny Valley’ will feel just as urgent as ever.

Main Image: Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead … (SD18) (detail), 2019, silver gelatin print, pins, 240 individual images, 5,7 × 9,1 m. Courtesy: the artist and Altman Siegel, San Francisco