Books

Man Booker Prize winner László Krasznahorkai goes to China in search of sorrow and destruction in his latest book

Man Booker Prize winner László Krasznahorkai goes to China in search of sorrow and destruction in his latest book

In 1990, the Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai made his first trip to China. It was the start of a decade of great transition for the People’s Republic. The Tiananmen Square protests had occurred only a year earlier, cementing communist rule. Seven years later, the British would hand Hong Kong back to the country – paradoxically and effectively introducing capitalism to the Party. It’s perhaps no coincidence that Krasznahorkai chose 1990 to visit the Middle Kingdom: the communist regime had recently fallen in the writer’s native Hungary and the raising of the Iron Curtain allowed citizens their first chance to travel the world freely. Hoping to become immersed in a land rich with a heritage independent of Western influences, Krasznahorkai instead encountered a China emerging from the ravages of the Great Leap Forward, its ancient culture either erased or being placed on display for the country’s burgeoning tourism industry. Krasznahorkai, in other words, was shocked to find a China on the cusp of modernity, more eager to profit from its past than to return to it.

Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens: Reportage (2004) has this year been translated into English and is Krasznahorkai’s first English-language publication since winning the Man Booker Prize in 2015. The title refers to the Classical Chinese expression for the world: ‘All that is beneath the Heavens.’ And, as he duly notes: this was ‘in their eyes […] identical with China itself’. Krasznahorkai’s additional words, ‘destruction’ and ‘sorrow’, reference what he saw as the commodification of China’s heritage. Throughout the 1990s, the writer returned to the mainland on several occasions, but it wasn’t until May 2002, when this travelogue is set, that he embarked on what he calls ‘a great journey’, in the region between Beijing and Shanghai, to find the evidence that China had not completely given way to the vicissitudes of the late 20th century.

Krasznahorkai is perhaps most famous for Satantango (1985), a novel which he adapted into a screenplay for director Bela Tarr’s formidable eponymous seven-hour film, which tops many lists as the greatest Hungarian film of all time. Krasznahorkai’s characters are often Beckettian, with the writer detailing their misery in majestically long sentences or putting them in absurd predicaments that paralyze their ability to escape to more hopeful situations. Accordingly, Susan Sontag famously called Krasznahorkai ‘the contemporary Hungarian master of the apocalypse’. But while the English-reading world was becoming familiar with the writer’s depictions of woeful Hungarian peasantry, Krasznahorkai had absconded the apocalypse in search of something more sacred. His 2008 novel of interwoven stories, Seiobo There Below, is an homage to the beauty of art and ancient crafts, particularly in Japan, where a bulk of the narratives take place.

Masterfully translated by Ottilie Mulzet, Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens, which predates Seiobo, bridges the dark visions of Krasznahorkai’s earlier work to the Buddhist-like meditations of his more recent books. It opens, unsurprisingly, with misery. Krasznahorkai (who refers to himself as László Stein in the book) and his unnamed interpreter have boarded a bus heading to Jiuhuashan, one of the sacred mountains of Chinese Buddhism. It is unnervingly cold and rain assaults the bus, which, hours into their ride, picks up a woman who proceeds to sit in front of them and open a window, letting in both the chilling rain and gusts of piercing wind. Later on, the narrator and his companion are almost robbed by two female monks.

At Jiuhuashan, they share tea with a Buddhist carver and Krasznahorkai asks him how he makes his Buddhas. The carver motions for him to witness his craft and begins to chisel away at a block of wood. Except, Krasznahorkai notes, this doesn’t serve to answer the question: ‘He does not know how that sacrosanct mournful beauty was conjured out of that wood, and he would almost start crying because he does not know … how does a Buddha emerge from this?’ The carver winks and merely suggests that: ‘He just carves nicely with his chisel until, well […] there is a Buddha.’ It may as well have been made in a factory.

Krasznahorkai’s search for authenticity is stymied again and again by depthless replies, aggressive modernity and postcard-ready China. When the two travellers visit a monastery, the abbot’s ringing mobile phone constantly interrupts their conversation; when the writer and his interpreter venture to a famous library of ancient texts, they discover only a façade – its contents having been warehoused for safety reasons. Occasionally, Krasznahorkai does happen upon a nugget of old China, such as Shaoxing, a historical city unspoiled by urban sprawl and decay, but he forces himself to leave it as if his presence might taint its purity. Visiting another idyllic village, he scurries to avoid a throng of camera-wielding tourists.

But the real essence of the book is in the many taped conversations the writer recorded along his travels. The prose stylistically breaks here, eschewing Krasznahorkai’s prolix sentences for an interview format. The Hungarian writer’s scrutiny of modern China is, in turn, scrutinized by those who live within it. At a dinner in Shanghai, Xi Chuan – an influential poet – challenges Krasznahorkai’s admiration for Ancient China: ‘Westerners love traditional Chinese culture, which, however, was purely dictatorial! [… ] Well, dictatorships are also really ancient! So they should love those too, right?’ Another poet, Ouyang Jianghe, pipes in: ‘We are living in a Time Zero […] neither in our past, nor yet in our future, [which is] presumed to be ever-wealthier, so that for us the ancient culture can only be beautiful in an idealized sense.’

It’s tempting to make a connection between Krasznahorkai’s lament for a bygone China and his bleak portrayals of Hungary under communist rule. He’s obviously not a fan of the institution. But idealism itself is a form of rule, and ancient traditions are tantamount to the very yoke that the new China is attempting to shed. Only by realizing the futility of his idealism does Krasznahorkai begin to liberate himself from its grip and acknowledge a deeper personal crisis: ‘It doesn’t matter where he is,’ he confesses to an elderly friend, ‘He walks along the street and he sees misery.’ Krasznahorkai later wanders around Beijing ‘like a lost man’ and falls asleep in a monastery courtyard where, in a dream, an apparition informs him that the heavens above have, indeed, changed and all that was once below them no longer exists.

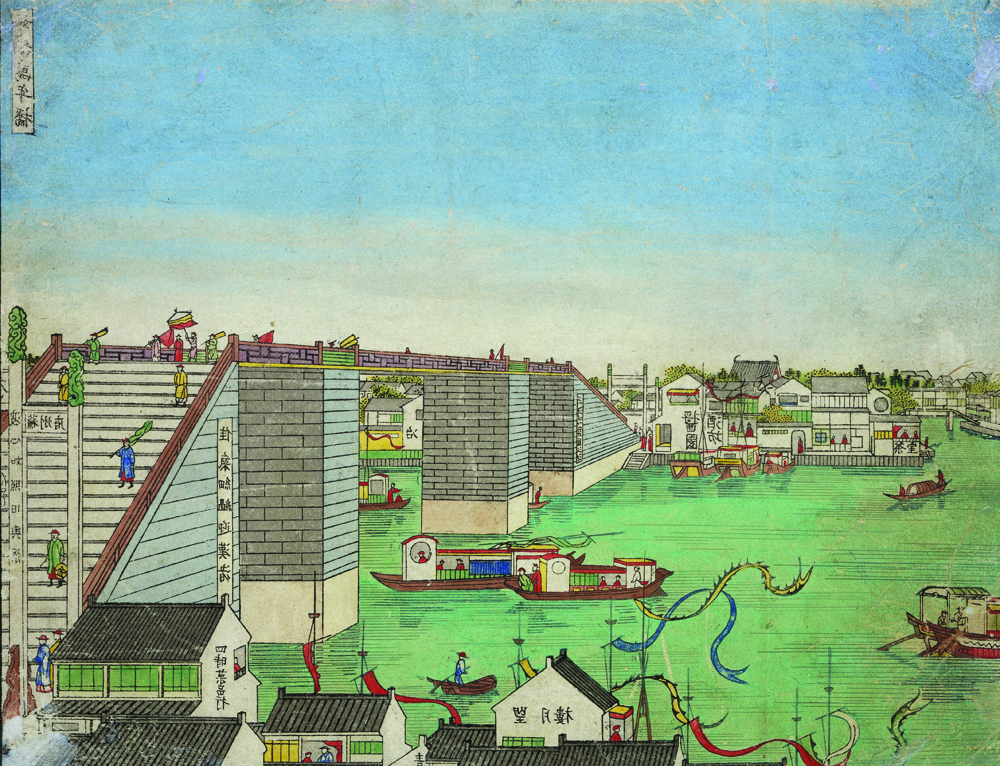

Krasznahorkai then receives instruction from a friend to visit the gardens of Suzhou, ‘the very citadel of the Chinese tourist industry’. The writer and his companion enter the Lion Grove Garden, and meet with its director, Fang Piehe, who assures him of its provenance: ‘Every tree and every plant has been placed there by a person; every strip of vegetation running along the wall has been planned by a human being.’ Krasznahorkai asks him what the intent of the gardens was for its original tender, expecting a philosophical reply. The director simply replies: ‘Joy.’ He meets another man, a couple of pages later, who merely shrugs: ‘The garden is an artificial creation [...] If I try to think of a location suitable for withdrawal, I would never seek out a garden [… ] Aesthetic is not of utmost importance. Neither is morality.’ It’s the pinnacle of a realization that builds throughout the book and, with it, Krasznahorkai allows himself to take pleasure in appreciating the past rather than decrying its loss.

Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens is, then, less of a travelogue than a personal document for the writer, a critical artistic step that has taken him to a more sublime era of his career. In the last pages of the book, Krasznahorkai notices sunlight bathing a vine-crawled wall and the image works as a perfect metaphor for his emergence into a more contemplative period of his writing life. It’s no accident, therefore, that Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens ends where it began, with that woman opening the bus window during an icy rainstorm. As a fellow passenger aggressively demands to know why she would do this, the woman simply replies that she likes the wind ‘because it blows’. It takes the whole book to appreciate that sentiment.