Carolee Schneemann, Jeff Preiss and Geeta Dayal Pay Tribute to Jonas Mekas (1922–2019)

The iconic filmmaker’s influence was felt across the length and breadth of New York in the 1960s

The iconic filmmaker’s influence was felt across the length and breadth of New York in the 1960s

Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal is a writer based in Los Angeles, USA.

New York City’s music scenes have always been full of towering egos and larger-than-life personalities, and the 1960s were no exception. Jonas Mekas played a key role in this scene, in part because he didn’t have a massive ego. He was a fixture, observer, facilitator, organizer, teacher, critic, collaborator and ally who helped will spaces into being with the strength of his resolve and his colossal work ethic. His legacy is not just in physical spaces, like the Film-Maker’s Cooperative and Anthology Film Archives, print media spaces, like the late and legendary magazine Film Culture (1954–1996) that he started with his brother Adolfas, or the voluminous quantity of films, poetry, and writings he produced. It is also in the psychic spaces he helped create – these possibility spaces of the mind.

Many people deserve credit for their contributions to The Velvet Underground mythos. Mekas wrote that it was the late Barbara Rubin who introduced Andy Warhol to the band, and not him, as is sometimes written. But Mekas’s role was undeniable. He provided the band with a space to rehearse, while Warhol learned how to make films in Mekas’s loft. The Velvets’ enduring visual mystique lives on through Mekas’s lens. His film footage of their first public appearance, in 1966, is not a straightforward document of the group, by any stretch. It is, like many of his films, nonlinear, diaristic and richly evocative. We see people in dreamlike flashes – a brief few seconds of Lou Reed on a guitar, Warhol in a suit, Edie Sedgwick and others, Nico singing. The camera floats and drifts about the room, occasionally darting around wildly. It perfectly mirrors the Velvet Underground’s music in a way that few films have.

Mekas helped many artists and musicians to explore new directions. He was a great friend to Yoko Ono and John Lennon, giving inspiration to their artistic practices and collaborating on projects. Tony Conrad’s entry into filmmaking was put forth by Mekas, who gifted Conrad with 16mm film stock to make his 1966 debut, The Flicker. And in 1973, when Conrad presented his ‘Yellow Movies’ paintings at the Millennium Film Workshop in New York, advertising the series as a ‘World Premiere Exhibition of 20 New Movies’, Mekas was the work’s most vocal supporter. ‘I find this exhibition one of the high achievements or products of the art of cinema and, to my thinking, Conrad’s best work to date,’ he proclaimed in the Village Voice. Like Conrad, Mekas was a polymath and a builder of community, who generated voluminous amounts of work across multiple generations without caring about mainstream success. ‘Tony Conrad is underground even in the underground’, observed the late percussionist, artist and mystic Angus Maclise in a 1967 article in Look magazine. The same could be said about Mekas: he was more radical and avant-garde than most of the avant-garde, quietly pushing forward and creating, across nearly a century.

Carolee Schneeman

Carolee Schneemann is an artist based in New York. Her retrospective, Kinetic Painting, was on view last year at MoMA PS1.

Scratch, scratch … tear, chew, claw, bite, kiss, exude, melt, scramble … camera, lights, action!

*

I’ve just phoned Scott MacDonald to share distress at our cultural future. Absent now: the life presence of Jonas Mekas with his camera. Celebrating the constancy of our shared lives.

*

You travelled beyond stench, loss, hunger, brutality, violence. Overtaken by Nazis, the medieval city of Vilna survives the Russian invasion, but the liberal state was brutalized, dehumanized … the Jewish community destroyed. Warfare whipped Jonas and his brother, Adolfas, into homeless refugee survivors.

I meet you in New York City – that magical wonderland. While at Bard College in upstate New York, I made adventurous forays into the city, replete with cultural riches where I can swim and dig like a muskrat.

*

In the welcoming apartment of Barbara and David Stone, early supporters of the avant-garde and devoted to film, I was introduced to two refugees from Lithuania, Jonas and Adolfas Mekas. The skinny brothers were enveloped in heavy, long, grey refugee coats, which I had only ever seen before in films of people who survived World War II. The Stones took the brothers under their wings, bringing them into the film world of the US.

I followed the development of other young artists making films through my close affiliation with US filmmaker Stan Brakhage, who had collaborated with the composer James Tenney on his earliest works – two radical spirits. As Jim and I entered the dynamics of New York City, the film community brought us into an association with Amy Vogel’s Cinema 16 artists – Maya Deren, Willard Maas – and we were fascinated to follow the Mekas brothers as they consolidated and extended the province of experimental film.

*

Jonas, always supple through the duress of worlds of chaos. You brought light, clarity, insistently embracing the quotidian … You blessed us with constancy, a devotion to all that can be seen, captured as a consecration of daily life. The beautiful and precarious chance to carry the sacred or obscene into what can be seen – we may see what we love without caution.

Jeff Preiss

Jeff Preiss is a US filmmaker known for his serial project of diaristic film installations and long-form narrative and non-narrative films. His long history of co-organizing alternative venues includes working with Films Charas, The Collective for Living Cinema and the gallery ORCHARD.

In a terrible instant, I understood that US filmmaker and curator Jonas Mekas was gone. My eye caught his picture on my Instagram feed, and I knew. An awful way to discover it. The moment came along with an intense sensation … physical, like the wake of his exit hit me and knocked me into some dark vacuum.

For me (and a lot of others – like everyone I know), Jonas’s life was the essential, inspiring ideal. We depended on it. If I hadn’t been exposed to him, his work, his ethos I doubt I would have ever become me. No one else holds a place like that for me as a filmmaker. No one else ever will.

Because of Jonas, I came to understand the personal and the social necessity of cinema. He’s why I laboured to understand the mysterious engagement that takes place in the viewfinder; how, through its scope, you exchange yourself with an inversion of the visual field and, in some synchronization between your objectivity and your mind’s-eye, a voice is inscribed in the image and projected back from the screen.

There’s way too much to say about the impossible scope of his life, but it was on the occasion of a life-changing screening that an overview of his work’s power came to me, all at once. I was studying at Bard with Mekas’s younger brother, Adolfas. He had driven up that day with Jonas’s brand-new print of the recently completed Lost, Lost, Lost (1976). A screening was improvised. I remember Adolfas being uncharacteristically solemn about it when he dropped the reels in the projection booth. What those cans must contain! I thought.

The screening completely jumped my life onto a different rail. Just seeing the opening inter-title reading ‘Diaries Notes and Sketches’ (which seemed to have migrated from the earlier film Walden (1969)) suggested an alternate filmmaking universe I wanted to inhabit and fight for.

Being a privileged student under Jonas’s influence came with its share of contradictions. Was it valid to adopt any of his language at all? It took some years of devoted labour to make sense of it. But there was always one intersection between his work and mine – clear from the start – that encouraged me to forge ahead. This was with my own childhood’s home movies. My intuition had suggested an intangible aspect of artmaking that Jonas seemed to confirm in his own use of autobiographical material. That the desire to film and to make films originated from some ingrained human nature that had long waited for the invention of the camera.

Virtually everyone told me that they thought Jonas would live forever. They literally believed it. It had to be that way. In Hollywood films, the commodity they cynically trade is the promise that you will be healed. Film is streamlined for this propaganda because it models the spirit. In Jonas’s cinema, his breath-like circulation inhaling the world and exhaling the self seemed truly sufficient to maintain his presence forever.

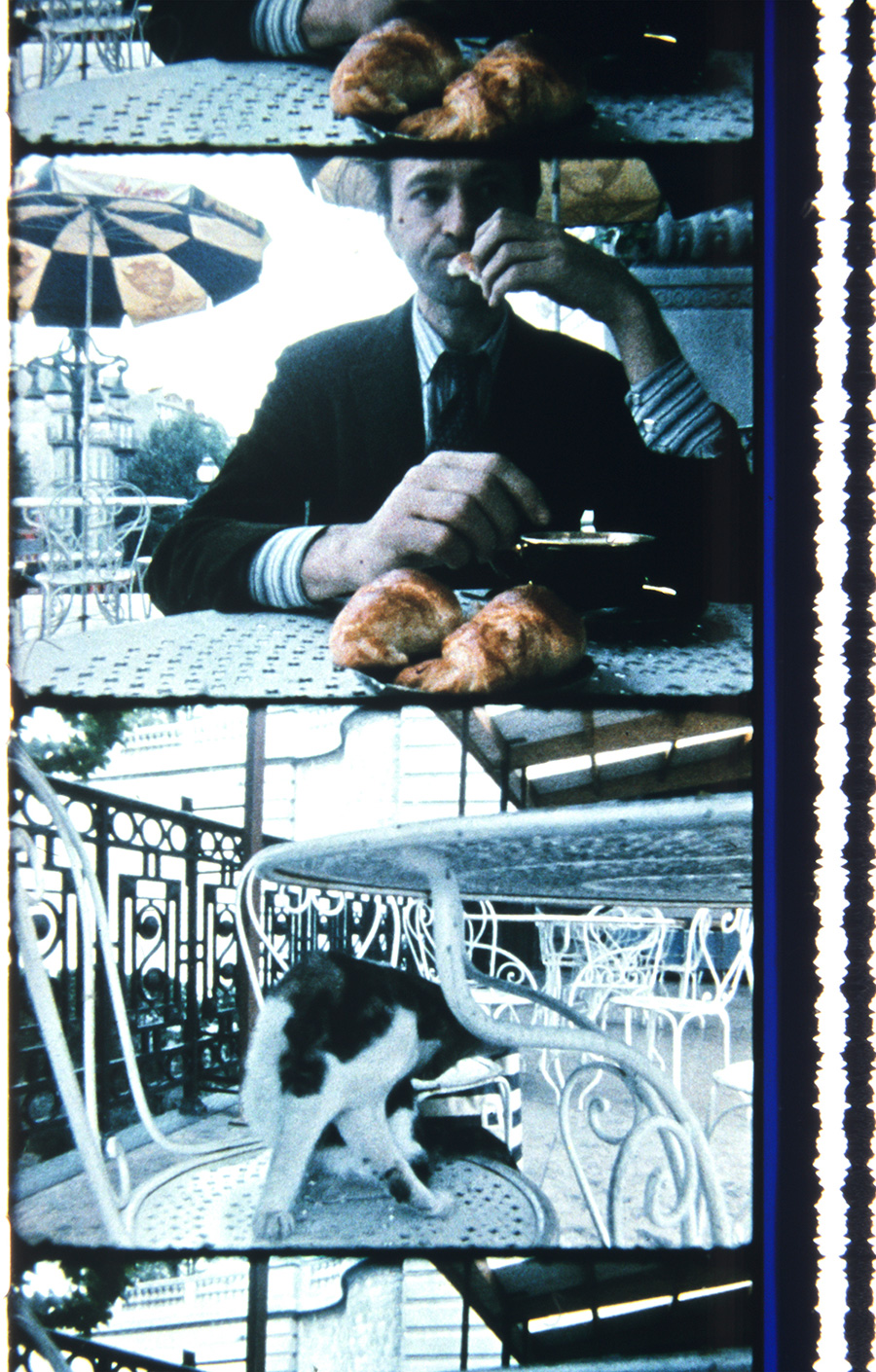

Main Image: Jonas Mekas at book signing in Paris, 2018. Courtesy: jonasmekasfilms; photograph: Wei Gao