Costume Drama

From Oskar Schlemmer and Cindy Sherman to Seth Price, Michael Portnoy and K8 Hardy, generations of artists have employed the codes of fashion and costume design. Vivian Sky Rehberg takes stock of the traffic between the worlds of art and dress

From Oskar Schlemmer and Cindy Sherman to Seth Price, Michael Portnoy and K8 Hardy, generations of artists have employed the codes of fashion and costume design. Vivian Sky Rehberg takes stock of the traffic between the worlds of art and dress

The contemporary art world is undeniably fashionable. In certain circles, and on many occasions, it is even exceedingly stylish. If you are the sort of person that clocks who is wearing what, you may note at any given art event that this microcosm is populated by a range of characters that appear in the fashion media and on the society pages: bearded hipster dealers rubbing their flannelled elbows with artists in bespoke suits; curators sporting nerdy vintage spectacles chatting with comfortably attired collectors in polo shirts and khakis; strictly sewn-up critics with signature hairstyles scribbling in tiny Moleskine notebooks. Clothing and accessories are key to how we visually communicate: they speak of where we come from, which sector of society we identify with, and can indicate our economic situation and our sense of creativity. Even if some remain faithful in their everyday dress to class origins, or to received ideas of social status and cultural belonging, it would be fruitless to base judgments about social distinctions on sartorial efforts. The ways in which dress factors into the self-fashioning of identity are far too complex. Post-opening under-the-table footsy alone can involve handcrafted leather brogues nudging red-soled Christian Louboutin stilettos poking at Chuck Taylor Converse All-Stars (on a floor littered with baseball caps and ‘it-bags’). In the dim light, you can never be sure which foot belongs to whom.

Yet, the contemporary art world is also deadly serious – a place where the swag bags are made from recycled cotton and groan with the weight of press packs and heavy theoretical tomes instead of chocolate truffles and Swarovski crystals. And because it cares to maintain that it is a serious place, the art world’s relationship to the garments and costumes that pervade it remains somewhat fraught. Art historian Nancy J. Troy, who has written about structural overlaps in production and distribution modes in modern art and haute couture, calls attention to the ‘paradox of fashion, which resides in its exclusivity on the one hand and its widespread recognition on the other’.1 A similar paradox underlies contemporary art, where the aesthetic boundaries between elite and popular culture have been all but completely eroded, but perhaps not to the extent that art warmly embraces the whole fashion industry into its ecumenical pantheon. Fashion is more comfortably seen as adornment. According to common wisdom, fashion is superficial and enjoys celebrity notoriety, while art is profound; fashion is trendy and fleeting, while art’s value has everything to do with its historical legitimization and longevity; the commercial aspects of the fashion industry drive aesthetic innovation, but art has a more dignified relationship to commerce. At the same time, as independent curator Ginger Gregg Duggan has pointed out, the terms we claim from and for art and theory – minimalist, conceptual, abstract, modern, postmodern, deconstructivist – have migrated into fashion (and to dance and theatre) and stayed.2

Biases of this sort are therefore becoming harder to take at face value without making semantic distinctions, and not only because crossovers between fashion houses, luxury brands and the visual arts are now commonplace, particularly where patronage is concerned. Today’s contemporary art scene would look very different without Cartier, Hugo Boss, Prada, LVMH and the Pinault (PPR) group, to name only some of the most visible high-end brands in the competitive quest for mutual benefits that are no longer limited to marketing and visibility, but are linked to shoring up cultural and financial capital in the present, as well as over the long term.

Critical and sociological recontextualizations of the historical relationship between art and clothing (to use a more neutral term) – undertaken in texts and exhibitions by scholars such as Troy, Duggan, Judith Clark, Caroline Evans, Hazel Clark and others – have paved the way for a re-evaluation of the current situation. Alongside the rise in academic interest in ‘fashion studies’, visual artists continue to work with codes, materials and modes of production that belong to the world of fashion at large, especially in print media and in physical displays. Artists such as Vivan Sundaram, K8 Hardy, Bedwyr Williams, Spartacus Chetwynd and Lucy McKenzie collaborate with designers or act as costume designers for the stage or themselves, mount fashion shows and incorporate elaborate costumes and everyday garments into their own work.

Adeline André, 2011, costume for Psyché ballet, Opéra Garnier, Paris

Although textiles and garments are perhaps not yet perceived as canonical artistic ‘media’, they have long figured in the artist’s material repertoire. Suffice to recall how dress and costuming, with the help of photography, have functioned in establishing an artist’s persona – or, rather, personae – in the case of Cindy Sherman’s work. But more prosaic than Sherman’s narrative-infused masquerades are the ways in which dress becomes associated with an artist as an everyday costume. Take Pablo Picasso in his favourite Breton sailor shirt (introduced to the mainstream by Coco Chanel, and still a high-street staple), as immortalized in black and white by Robert Doisneau in 1952, or Andy Warhol’s trademark silver-white hairpieces, endlessly pictured in the media. Joseph Beuys’s felt fedora and fisherman’s vest were not only accessories, but so essential to the foundation of his own mythology they serve as stand-ins for the artist and his ethos. Beuys first wore his Filzanzug (Felt Suit, 1970) during the performance Action the Dead Mouse / Isolation Unit (1970) before it entered collections as an art work multiple to be hung on the wall. Yayoi Kusama’s trademark polka dots in brilliant contrasting colours are scattered across her paintings, sculptures, installations, performances and clothing designs. The costumes like those employed by these artists are imbued with personal and social symbolism. They reflect or deflect knowledge of a person’s identity, and they can contextualize one historically or serve as a uniform that promotes notions of timelessness and conformity to specific ideals. Integrated into daily life, a costume helps us to construct and display a self-portrait, and one that frequently challenges a spectrum of normative ideas about the body, gender, race and class (Rrose Sélavy, Grayson Perry, Claude Cahun, Eva & Adele and Orlan come to mind).

Yinka Shonibare’s mixed-media work employs richly coloured and patterned costumes made in ‘Dutch wax’ fabrics, which originated in Dutch colonial trade and have become strongly associated with African identity, and he frequently updates historical art works as a means of critiquing colonial and Enlightenment history. Shonibare often relies on headless mannequins in his installations such as Leisure Lady (with Ocelots) (2001). But he has also worked with live bodies. In 2005, in his film Odile and Odette, he collaborated with London’s ROH2, the contemporary arm of the Royal Opera House, on a reinterpretation of the 19th-century ballet Swan Lake. Here, the duelling black and white swans – a dancer from the Royal Ballet and a dancer from Ballet Black, because the Royal Ballet had no dancers of African descent in their corps – wear matching costumes and ballet slippers in a muted Dutch wax print, and perform facing each other as if mirror-reflections. More recently, Elad Lassry collaborated with members of the American Ballet Theater and New York City Ballet for the dance performance Untitled (Presence 2005) at the Hayworth Theater in Los Angeles and Untitled (Presence) (both 2012) at the Kitchen in New York, for which he also designed the costumes.

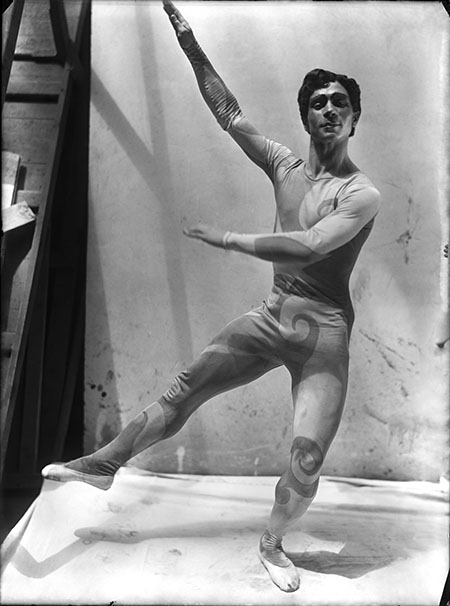

Of course, stage collaborations among artists, designers, musicians and choreographers are part of a venerable tradition, and one of the richest where costumes are concerned, from Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (costumes by Sonia Delaunay, Natalia Goncharova, Henri Matisse and Picasso) to the Bauhaus artist Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadisches Ballet (Triadic Ballet, 1927) to the Judson Dance Theater and Merce Cunningham Dance Company, which famously worked with Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Nam June Paik and Marcel Duchamp. More recently, in 2011, French haute couture designer Adeline André, who redesigned the costumes Rauschenberg originally created for Trisha Brown’s Set and Reset (from 1983), teamed up with painter Karen Kilimnik, for whom ballet is a passion, to devise sets and costumes for choreographer Alexei Ratmansky’s 2011 staging of the ballet Psyché in the opulent Opéra de Paris. Kilimnik’s loosely brushed oneiric land- and skyscapes – enlarged versions of several extant paintings – were shimmery complements to the music of Belgian-French Romantic composer César Franck. They provided a lush and vibrant backdrop for the dancers in André’s costumes, especially the liquid-gold, bias-cut sheath worn by the goddess Venus, and the evanescent, almost immaterial robe worn by the mortal Psyché.

Nicholas Zverev in Parade, 1917, costume by Pablo Picasso for Les Ballets Russes

According to André, when working in such a collaborative way, the designer must draw on the original narrative or symbolism of the dance, negotiate proportions offered by the artist in the set-design and remain aware of a range of technical concerns, not least of which is the movement of the body in space, but which also includes the physical qualities of the fabrics she is working with.

Performance encompasses and traverses disciplines, and though costuming is a large part of it, its visual significance and impact varies so widely it is difficult to generalize. Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964), in which she invites the audience to mount the stage and snip away parts of her dress with shears piece by piece – and which I had the occasion to see restaged in Paris in 2003 – succinctly and powerfully expresses trust and physical vulnerability. By contrast, the clothing Michael Portnoy wears during performances is arguably part of his inventory of ‘power tools’. Portnoy frequently collaborates with designers threeASFOUR, and one could make this claim for the dark, cut-out power suits worn by Portnoy, Ieva Misevičiūtė and Johnnie Moore in their roles as hosts of the linguistic game show 27 Gnosis, performed at dOCUMENTA (13) this year. But it is quite literally the case with a pair of ‘vocal power tools’ – wooden clogs with toe boxes that are curved like the blades of a sleigh and extend up toward the mouth. Portnoy designed these with Oliver Sudden, a former tenor and the nephew of the late Boris Vian, for his performance The Dudion Levers (2008). For their design, they relied on sketches found in Vian’s archive for an instrument that would massively amplify the voice. The shoes function as an adaptation of this instrument and are crafted to help send the performer’s voice through the body, from the feet up to the throat, and out to the audience.

For the time being, contemporary art’s sartorial ventures show little sign of abating. Also at dOCUMENTA (13), Seth Price presented Spring/Summer 2012, a collection of white, military-inspired garments designed with Tim Hamilton, both in a fashion show and in a department store window. Months earlier, at the Whitney Biennial, K8 Hardy’s Untitled Runway Show (2012) used a catwalk built by fellow artist Oscar Tuazon to feature repurposed thrift-store clothing of her own design.

Seth Price in collaboration with Tim Hamilton, Spring/Summer 2012, fashion show at dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel

As the previously separate performative spaces of clothing and art start to collapse into each other, it is perhaps worth keeping in mind John Kelsey’s assessment that fashion serves as an accurate barometer of the present. A member of Bernadette Corporation, which has been pioneering art/fashion crossovers since the 1990s (see their autumn/winter 1997 collection Hell on Earth), Kelsey writes: ‘More mobile and exposed, in certain ways fashion remains the more effective means of processing the chaos of the present, probably because, as a sociocultural mediator, it is itself already highly mediated and because, while sticking close to the body, it is ever so responsive to how quickly the ground shifts under its acid-treated zombie-vein heels.’3

Strangely enough, Kelsey’s words, here about self-taught designers Kate and Laura Mulleavy – the fashion-design duo who collaborate as Rodarte – echo those of Walter Benjamin, who wrote about fashion at the beginning of the 20th century in his Arcades Project (1927–40): ‘For the philosopher, the most interesting thing about fashion is its extraordinary anticipations […] Each season brings, in its newest creations, various secret signals of things to come. Whoever understands how to read these semaphores would know in advance not only about new currents in the arts but also about new legal codes, wars and revolutions. Here, surely, lies the greatest charm of fashion, but also the difficulty of making the charming fruitful.’4 Some will surely take solace in the fact that Benjamin also warned: ‘The more short-lived a period, the more susceptible it is to fashion.’5

1 Nancy J. Troy, ‘The Theatre of Fashion: Staging Haute Couture in Early 20th Century France’, Theatre Journal, 53:1, Theatre and Visual Culture, March 2001, p. 24. Troy’s impressive book Couture Culture: A Study in Modern Art and Fashion (mit Press, 2002) expands on the above article, which treats French couture designer Paul Poiret’s aesthetic and commercial strategies with respect to the popular theatre, to draw further parallels between Poiret’s activities and those of gallerist Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and between industrialized production in ready-to-wear fashion and the readymades of Marcel Duchamp.

2 Ginger Gregg Duggan, ‘The Greatest Show on Earth: A Look at Contemporary Fashions Shows and Their Relationship to Performance Art’, Fashion Theory, 5:3, 2001, p. 262

3 John Kelsey, ‘Riches to Rags’, Artforum, April 2010 (xlviii, No. 8), pp. 75–6

4 Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin trans., Belknap/Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1999, pp. 63–64

5 Ib