Gwangju Biennale: Imagined Borders

This year’s edition acts as a house of mirrors reflecting the promises of globalization and the ‘intensification and erosion of nationalism’

This year’s edition acts as a house of mirrors reflecting the promises of globalization and the ‘intensification and erosion of nationalism’

In his review of the inaugural 1995 Gwangju Biennale, in the pages of this magazine, the art historian Lawrence Chua wrote: ‘For a biennale curated under the bold credo “Beyond the Borders”, the exhibition seemed more intent on preserving boundaries, carving up the world as curatorial territory. In a new “globalized” economy where capital is a stateless proposition, there has been both an intensification and erosion of nationalism.’ Most visitors to the biennial’s 12th iteration know of its origins as commemoration for the May 18 Democratic Uprising, in 1980, which saw hundreds of protesting civilians in the city gunned down by the troops of dictator Chun Doo-hwan. Fewer might be aware that its inaugural edition coincided with the implementation of President Kim Young-sam’s segyehwa(globalization) policy: a top-down programme of economic liberalization and labour reform. In his 1995 new year’s address, Kim stated: ‘Globalization is the shortcut that will lead us to building a first-class country in the 21st century.’ In much of Gwangju – including, notably, the cavernous Asia Culture Centre, which opened in 2015 at an estimated cost of US$680 million and hosts part of this year’s biennale – it is hard not to feel that his optimism has been at least partially borne out. But so, too, has the simultaneous ‘intensification and erosion of nationalism’ presciently diagnosed by Chua – in ways, by turns, wildly unpredictable and depressingly familiar.

This is the world the 12th biennial seeks to address. Titled ‘Imagined Borders’, in direct reference to the 1995 edition, it is a fairground house of mirrors in which the early promises of globalization return to us riotously distorted if not comically ugly. Curated as seven individual exhibitions by a total of 11 curators, and featuring work by 163 artists from 42 countries, its sections address, amongst other things: displacement and migration (Gridthiya Gaweewong’s ‘Facing Phantom Borders’); supranational power structures (Christine Y. Kim and Rita Gonzalez’s ‘The Ends: The Politics of Participation in the Post-Internet Age’); and the ideological spectres of architectural modernism (Clara Kim’s ‘Imagined Nations/Modern Utopias’). The resulting show, unfortunately, is as vague and politically anodyne as its title suggests.

There are moments where the intensity and specific messed-up-ness of the present are brought keenly into focus. In ‘The Ends’, Zach Blas’s Jubilee 2033 (2017) re-imagines the urban post-apocalypse of Derek Jarman’s eponymous 1978 film as a world after the fall of the oppressive super-state of the internet. In cyber-baroque operatic glory, it pits Silicon Valley’s Randian individualism against the queer resistance communities of Nootropix, a genderfluid AI prophet, whose climatic (in many senses) dance routine to the rousing melody of Andrea Bocelli’s ‘Con Te Partirò’ (1995) will stay with me for some time.

‘Facing Phantom Borders’ opens with Kader Attia’s Shifting Borders (2018). A multi-channel film installation, it presents interviews with spirit mediums and healers using pre-modern traditions to deal with contemporary trauma – much of it the fallout of colonialism. Wooden chairs bearing the artist’s trademark prosthetics are interspersed between low-placed screens – a rather clubfooted evocation of phantom limbs, perhaps, but nevertheless powerfully evocative of the sense of collective loss on the Korean Peninsula whose severing at the 38th parallel, as one interviewee remarks, no-one imagined would be permanent.

Elsewhere, in ‘Imagined Nations/Modern Utopias’, empty plastic bags litter Mauro Restiffe’s captivating, large-scale, black and white photographs of Brasilia during the 2003 inauguration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (‘Inauguration’). These take on added poignancy as Brazil, with general elections approaching, veers away from the leftist ideals upon which Lula (currently in prison on corruption charges) was elected and towards right-wing populism.

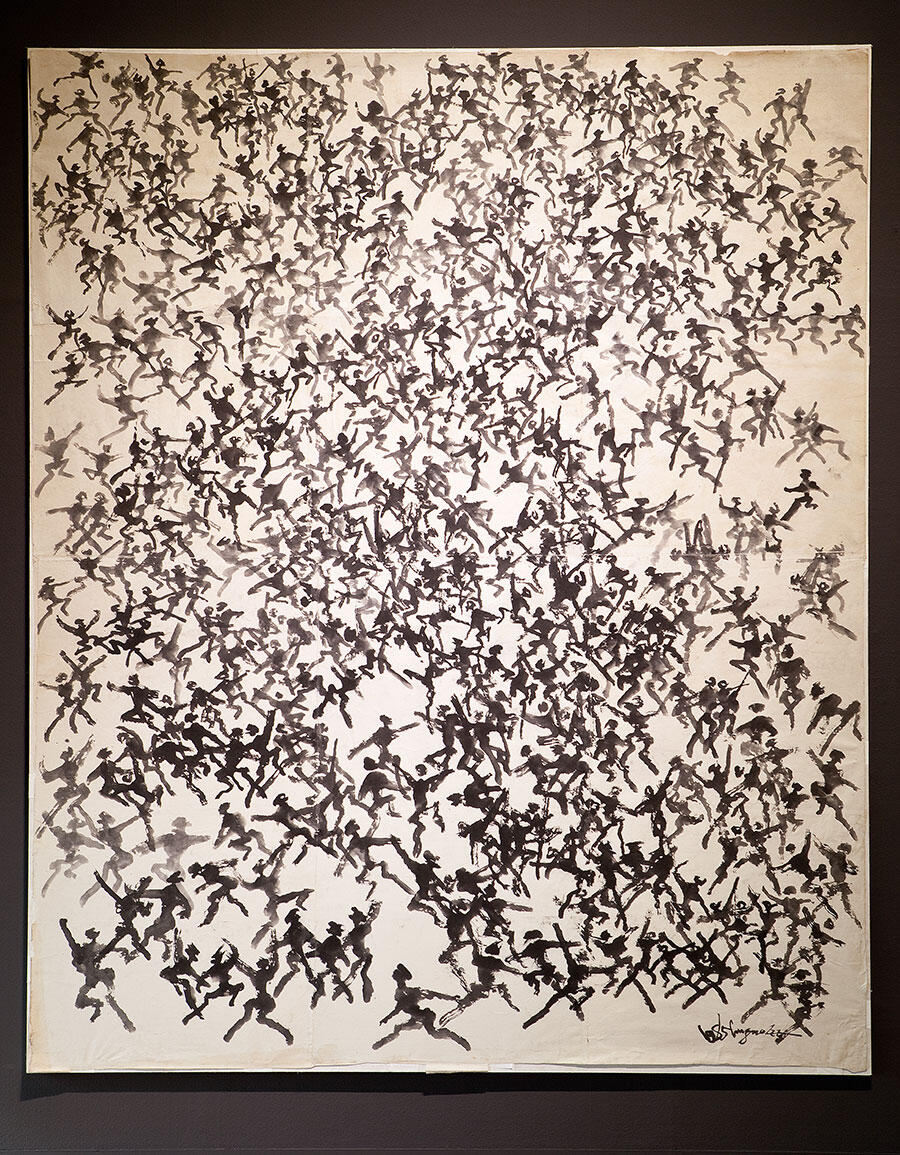

Also successful is David Teh’s acupunctural insertion of works from the 1995 biennial into his co-curators’ presentations. In ‘The Art of Survival: Assembly, Sustainability, Shift’ (curated by Man Seok Kim, Sung woo Kim and Chong-Ok Paek), for example, the crowds of black, inky stick figures in a suite of large paintings onhanji paper by Lee Ungno (c.1980) evoke an art history that stretches from the Lascaux cave to Sol LeWitt and the repetitive mark-making of dansaekhwa. They were painted in response to the 1980 bloodshed in Gwangju. Accused of spying for the North and imprisoned between 1967–69, Lee lived in self-imposed exile in Paris from his release until his death in 1989; the public display of his work was banned in South Korea for a number of years. Are his stick figures marching or dancing? Embracing in celebration or running, arms outstretched, in fear? With the simplest of forms, Ungno evokes our inescapably plural existence as well as the bewildering ambiguities of our relations with one another.

Perhaps most remarkable of all is ‘Paradoxical Realism’ – a show of North Korean chosonhwa (traditional ink-wash painting), curated by B.G. Muhn. Grouped by genre, these enormous, recent works on paper combine motifs of national myth-making – familiar from Soviet and Maoist socialist realism – in virtuosic, luminous detail. Though relations between North and South Korea are currently warmer than in recent years, this is not an ‘official’, state-endorsed exhibition. It is likely to be the first time most visitors, South Korean and international, have seen such works. The 22 paintings here come mainly from private collections, mostly in China: even in North Korea, where artistic production is government controlled, there is evidently an export market. In Choe Chang Ho’s At an International Exhibition (2006), a group of girls in traditional hanbok dress huddle around a glowing MacBook, the diaphanous fabrics and salon setting perhaps unwittingly recalling Edgar Degas’s backstage scenes at the ballet. As the South Korean government madesegyehwa an official policy, North Korea pursued its doctrine of juche, or extreme self-reliance. In its startling overlay of chronologies, geographies and cultural contexts, it is – tellingly – this propaganda set piece that poses the 12th biennial’s most complex questions about globalization and its discontents.

The 12th Gwangju Biennale runs at various venues in Gwangju until 11 November 2018.

Main image: Choe Chang Ho, At an International Exhibition (detail), 2006, ink wash on paper 107 × 159 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Gwangju Biennale