Head Space

A conversation between Ed Atkins and Matthew De Abaitua about the intertwining of art and technology

A conversation between Ed Atkins and Matthew De Abaitua about the intertwining of art and technology

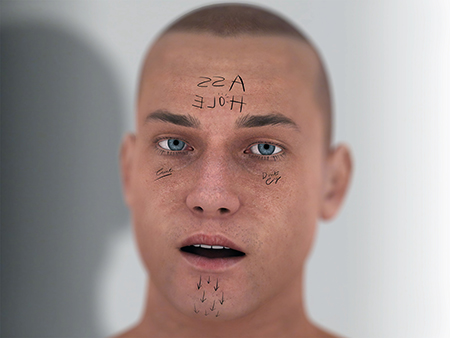

I meet with Ed Atkins in a side room of Cabinet, a London gallery close to the cluster of tech start-ups around the Old Street roundabout. As a science fiction writer, I’m interested in how technology is changing us, and how art is tracking those changes. Atkins’s video work ‘Ribbons’ (2014) – which, on different screens, formed the heart of his recent untitled solo exhibition at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery in London – follows the self-debasement of a naked, tattooed, computer-generated avatar as it puts away the fags and booze with abandon. It speaks with Atkins’s voice.

The avatar can play the doppelgänger, unleashing the dark self. The troll. The hater. But ‘Ribbons’ also explores how we are in a feedback loop with technology. At the entrance to the Serpentine exhibition, a screen showed a computer-generated head bouncing endlessly down a flight of stairs; it created a grisly punctuation. The loop is a signature of our times, whether in musical beats or GIFS. The loop is repetition, over and over again in the now. It’s very important to be kept in the loop.

Matthew de Abaitua In ‘Ribbons’, a computer-generated avatar of a very drunk man sings two songs: J.S. Bach’s ‘Erbarme Dich’ from St Matthew Passion (1727) and Randy Newman’s ‘I Think it’s Going to Rain Today’ (1968).

Ed Atkins There’s also a Henry Purcell song in the middle, ‘Tis Women Makes Us Love’ (1730), which Dave sings when he’s lying on the table in the pub. There’s a sense of how manipulative songs can be – they can make you cry and deeply move you, and I’ve always wondered why that was. Why am I feeling these so called authentic emotions in the face of this song that seems so cynically manipulative?

MA Just because it uses the form doesn’t necessarily mean it’s cynical.

EA True, but you can almost formulaically work these things out. All of the songs in ‘Ribbons’ were originally performed by men singing in a mournful, failed way. The impression is one of men pleading for forgiveness for something darkly ambiguous. Newman’s thing is a kind of wallowing in stock melancholy; the Purcell performs the never-ending cycle of getting drunk, going mad and falling in love. In the same way that booze might function as an emotional catalyst and dramatist, singing when you’re drunk is egging that on; it confirms the melodrama. The songs and their contexts affirm and maintain that performance throughout history.

MA Why is the avatar called Dave?

EA You can buy the avatar off the shelf in a foetal state, as it were, and he’s called Dave. I guess the person who modelled him was thinking of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and the dying refrain of the ship’s computer HAL 9000.

MA It’s an appropriately blokey name. Dave is a drunken avatar under a table, slinging back drinks, smoking fags, filling up cups with fluids of various viscosity – bodily and otherwise. What is the emotional function of avatars, in terms of doppelgängers and other selves?

EA It’s part of a history of masks, in performance particularly and in acting more generally. What does it mean to don a mask, and what does that kind of anonymity allow? Most of this came from the sorts of things I have been writing over the last few years. At first, seemingly unthinkingly, my writing became misanthropic, horrible, undermining and guilt-ridden. I wanted to understand this and not remediate it within the work. I wanted the avatar to allow that stuff, to go all the way and to demand empathy in the face of its obvious fakery. It’s a violent plea, and these male figures are unforgivably and dangerously pathetic. But in spite of that – because of that – I want them, Dave et al, to be deeply empathetic. An empathy that’s based on something more complicit, much trickier to own up to.

MA Do you think that technology increases our emotional range?

EA In a way.

MA I know it sounds paradoxical, because we’ve inherited our concepts of technology from the 20th century, with a popular vision of robotics and computers as being unemotional, but a hyper-emotional aspect to technology is emerging.

EA I wonder whether this is technology’s effort to encroach upon the emotional, the affecting. And by technology, I mean its directors. The fascinating limit for me – and where I want to work – is the histrionic attempt to dramatize, to re-present, emotional things. Sentimentality and romance and hate and violence are performed in their extreme, because they immediately highlight the problems and failures of technology in trying to represent that thing.

I suppose I imagine that people’s response to my work reflects something about themselves, rather than about the cool capability of the avatar. But, at the same time, the work certainly touches upon the continuous honing of the representation of emotional sentiment by the machine.

MA The avatar is naked, though it’s not candid.

EA Yes! And how could it be? It’s virtuosic and totally abject. It’s grossly pathetic and grounded. I don’t really know what it is to de-tumesce an image, to negatively claim something – to say what it was and how it felt, determinedly.

MA Are you a romantic?

EA Not wholly. I want romanticism to be overtly connected to materialism. My attempts with my work are more often as dumbly visceral as they are emotional. I want the sub-bass and the edit to demand a physical as well as an emotional response, but perhaps to the same end, where romance might have some relation to the sublime. It’s kind of an apology and, importantly, a ‘fuck-it’ – the collapse of an attempt to convince oneself of the beauty of things. Or to think of beauty as wholly recuperated.

There is also the question of how far one can plummet between one thing and the next, and whether that’s a literal distance – landing with a physical thud – or an impossible one, where you’re pushed into imaginary, metaphorical terrain. The right uses of literality and metaphor.

MA What does art writing mean to you?

EA I have no idea. I’ve always been terrified that the word ‘art’ functions as an apology in that situation.

MA An apology for what?

EA Well, that it’s apparently easy to get away with something under the auspices of art. And I don’t know what that thing to get away with even is.

MA Lack of punctuation?

EA Ha! That’s not exclusive to art. That’s in poetry, too.

MA But in poetry every word is sweated out of the poet.

EA Not necessarily, right?

MA Some poets dine out for the rest of their lives on one good hour of work whereas prose writers like myself are the long-distance lorry drivers. To write 100,000 words, you’ve got to sit in the cab every day for a year, and that makes prose writers dour and managerial people. From the perspective of a professional writer, there is a verbosity to art writing, in which the language is used concretely, for its special effects.

EA I’ve always wanted my writing to speak experientially. What is it to write and to read these things? The experience of that, in itself? Coherence is held in such high regard – but what are the conditions of sense-making and according to what criteria? The hidden agendas of comprehensibility! I’ve always felt the urge to speak or to write and to not necessarily know what I want to say. That, in itself, creates a momentum and a rhythm and a meaning, without recourse to too many presumptions.

MA You’ve said in the past that you start with writing as your process?

EA Yes. Often with a turn of phrase or something I can repeat or build into a rhythm. The small book, A Seer Reader (2014), which I made for the Serpentine show, is a series of aphoristic prophesies written in the future tense. It’s infinitely easier, and more freeing, for me to write a sentence than to draw a picture. MA Your writing alternates between moments of great lucidity and theory. The improvisatory act of writing is also the creation of the work.

EA Yes! I’d like very much to be the ideal reader of my own work, and that would certainly include a not-knowing – not ‘ideal’ as in moral fantasy. In ‘Ribbons’ there is a lot in there that is importantly uncomfortable to me. Not just because I’m embarrassed at the singing and stuff, but because I find it a hard piece to stand by, more so than anything I’ve done before. There’s a lot in it that is dodgy and that totally risks misinterpretation. It’s duplicitous in terms of its allegiances.

MA When I said I found your work immersive, that’s the quality I’m responding to: you can’t possibly think through all the intellectual and emotional implications of what Dave is saying. You can’t control it, and that abundance of material is novelistic.

EA It’s horrible; it’s virtuosic abjection. Which is how I feel about a lot of what is novelistic.

MA To return to technology, Google’s search algorithm anticipates our desires before we have entirely formulated them. Does your work respond to the age of algorithm?

EA It does, but more in response to how those algorithms feel to us non-algorithmic beings. Though that predictive element is important. There’s a wider issue: that of determining consensus. This lead to the idea of coherence, to the Facebook idea of only being able to ‘thumbs up’ something; there’s no thumbs down. That affirmation is the only convenient possibility.

MA The ‘thumbs up’ appears in a film you made last year, Even Pricks.

EA Yes. It’s a site of allegory in lots of different ways. It’s a defining aspect of anthropomorphic tool-wielding as well as of the pollice verso kind of condemnation: thumbs up or thumbs down, live or die. It’s also the brutish digit: the penetrative phallus.

MA The thumb is the instrument of power. This knowledge is embedded in the user interface of smartphones. You use your thumbs for a Blackberry, the device for work, for control; the discovering, indicative finger we use for operating the iPhone is more of a magic finger. There is knowledge embedded in these haptic gestures.

EA Obviously a lot of technology now is working hard to maintain its sense of magic and mysticism – meaning our ignorance of its workings – in order to obscure the reality of its production. We use words like ‘immaterial’ to talk about digital stuff although, pretty obviously, matter hasn’t gone anywhere. It’s just deflected from our immanent reality to a mine, or indexed on the body of a sweatshop worker.

MA The tablet is cheap because it’s a window through which an algorithm can study you and be trained accordingly in human desire.

EA Absolutely. It’s logical that in our culture we’ve ended up with things like Facebook and social media as the pre-eminent ways of existing. More relations are formed and more networks exist in those versions of our lives than in this one, sitting here.

MA What’s your understanding of ‘post-internet art’?

EA To me, it was always a jokey misnomer but, simply put, I suppose it’s art made after the advent of the web 2.0. It came into being at the same time as the so-called speculative philosophies – Bruno Latour’s theories around levels of reality, of networked reality. I love the idea of a dragon being more networked than my shoe, which would mean a dragon is more real than my shoe.

MA Are you influenced by science fiction?

EA I like Grant Morrison. I read his comic books, The Invisibles, but what really stuck with me was the lecture he gave last year at the ‘Disinfo’ conference on ‘magick’ – he was pissed and on ecstasy – which I thought was incredible as a performance. I’d got so clogged-up by art theory and philosophy, and here was this guy performing something so complicated, so idiosyncratic. It catalysed something for me. He was saying things like: ‘I went to Kathmandu to be abducted by aliens – and I was.’ His pitch was that of a salesman of magical thinking and practice, it was like: ‘Hey, come on, anyone can do this stuff.’

A lot of the text in ‘Ribbons’ – rendered in blockbuster type, an advertising vernacular – is totally underwhelming or intimate or personal in its possible reading as text. Obviously, this also speaks of what it is to sell oneself – the use of oneself as the commodity, in a way – which is some super-extension of biopolitical power.

MA Biopolitical?

EA Insofar as Michel Foucault’s analysis of how the state’s giving us the responsibility to maintain ourselves is a way of pushing governmental power into a place where it doesn’t have it. It’s like an embodied panopticon: we don’t just self-regulate, we sell ourselves now. We don’t need an external product.

MA The first thing I saw on walking into the Serpentine Sackler Gallery was a loop of a severed avatar head bouncing down the stairs.

EA The eyes are open; it’s as alive and dead as a CGI thing can get.

MA It reminded me of those experiments where people try and figure out whether the head of the prisoner briefly survives the guillotine. I read about a case where somebody slapped a severed head.

EA And, it winced?

MA It looked indignant. That really is the stuff of nightmares.

EA One of the formative films I watched when I was a kid was Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, Wrath of God (1972). There’s a scene in which two mutinous soldiers are talking around a campfire and Aguirre can hear them. One of them is counting down from ten and, at four, Aguirre chops his head off. The camera follows the head, and it continues to count down to zero before it dies. I made a piece in 2012, called Us Dead Talk Love, which was ostensibly two severed CGI heads.

The image of a severed head obviously speaks wholly, iconically, of mortality; but I also enjoy the image of it indefinitely tumbling down the steps – the immortal CGI performance. Procedural. A favourite book of mine from the last couple of years is The Severed Head (2012) by Julia Kristeva. She curated a show of historical sculptures and paintings of severed heads in the Louvre a couple of years ago and wrote a great book about the history of decapitation, from Medusa’s capital hermaphroditism to Caravaggio’s self-portraits.

MA Removing a head is like removing theory, ideas and the imagination, leaving behind only the body.

EA ‘Ribbons’ has a sense of repleteness. Every frame is bulging with its own anima; it can’t really go anywhere; the whole thing is turgid.

MA Could you talk a little about your video No-one Is More ‘Work’ Than Me, which you’ve just finished making?

EA I was asked to make a piece for a show called ‘14 Rooms’, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Klaus Biesenbach, with the Fondation Beyeler and Art Basel. The rooms all had the same dimensions, and in each one a performance took place. It included canonical works by artists like Joan Jonas and Marina Abramović, so it was like an animated museum of performance in a way – but with an ominous, domestic dimension. There were several rules for making the work, one of which – I’m surely paraphrasing incorrectly – was that you had to encounter a person who was not the artist but who loiters between sculpture and person, so it seemed like a perfect opportunity to push the avatar thing. The one I used is a lower grade version to Dave – a prior incarnation. It was an eight-hour performance through a CGI figure. There was a large screen and a live performer, who didn’t really do anything save remediate. The avatar is basically pitching himself, trying to ingratiate himself: he constantly addresses you and asks you to look into his eyes, to connect. He’s got a bit of blood trickling out of his nose and he keeps saying: ‘Don’t look at the blood.’ He is proud of the blood, distracted by the blood. It’s a weird performance.

MA Eight hours of improvisation? Did you always know where you were going?

EA I had these reset motifs, and lots of karaoke as well. The avatar is constantly singing Bryan Adams’s song ‘Everything I Do (I Do It for You)’ (1991), and Buddy Holly’s ‘Everyday’ (1957). It’s a horrible thing! No One Is More ‘Work Than Me’ was also made trying to think about certain forms of immaterial labour. It was bluntly about doing a working day and convening never-ending, immaterial labour and manual, embodied labour. I made something that is, I think, kind of tortuous to sit through.

MA Was there a point in your childhood when ‘Everything I Do (I Do It for You)’ was played endlessly?

EA I fucking loved that song, yes! I recorded it off the radio, in 1992 or so.

MA You would have been around 12 then?

EA Yes, something like that. 10. I had my ghetto blaster and I’d desperately try to record it without a DJ interrupting. I’ve always loved that song, in spite of knowing what it is. It’s not a guilty pleasure, which I don’t really believe in as a concept; it’s this kind of pop that is perfect, engineered and personal.

MA Is that why you associated it with work: common sentiment, something that most other people do?

EA More for its familiarity; it’s a song that is pretty much emptied-out. There are also particular bits of classical music I use throughout the work, which are mainly familiar from car ads or mood CDs or Classic FM. They’ve been endlessly re-purposed and re-sold; they’re tired or desperate in certain ways. I thought: it’s hysterical, this figure desperately trying to please you, with no real referent, and nd then telling you to ‘fuck off’ but then ‘shhh, shhh, listen to this’, and then playing it again.

MA Sometimes, if a man is drunk, he likes to coerce people into listening to the music that has an emotional impact on him. I don’t know whether this is gender specific, but I remember my brother-in-law once saying: ‘Listen to this, you’ve got to listen to this, this will absolutely blow you away. You’ve never heard anything like it,’ and then he played me Dire Straits’s ‘Brothers in Arms’ – in 2004. I suppose what we’re doing by putting ourselves into technology is partially about the promise of preservation.

EA The thing about performing into a low-grade avatar is that you’re not entirely sure what is being inflected, and to what end. He gets frustrated by his inability to communicate, which creates a horrible exchange, this lopsided, excessive emotional debt, recouped through abuse. Throughout the performance, the songs and talking are sound-tracked by the whirring fan of the laptop, which lifts the avatar, overstretching itself and overheating, over the course of eight hours.

MA You started out filming real things and then shifting into making CGI.

EA I shifted deeper into CGI because it offered the possibility of nothing dying – it seems generative rather than regenerative; originary rather than vampiric. And I always found it hard to film people and edit them.

MA When you’ve used real people in the past, you’ve filmed the backs of their heads.

EA I wanted people to watch these films and hold on to what an edit was doing, rather than some illusionary transparency of traditional montage, where you’re not supposed to feel the cut and its violence. Filming a face always collapsed the structure and the possibility of its visibility. You’ve suddenly got a real person, effectively outweighing all those subtleties you might have worked so hard to maintain. CGI circumnavigates that imbalance to a certain extent, because you’re never given a real space or a real protagonist. Analogue, like depth of field, is faked all the time – as if there’s a fucking lens! It’s saturated with analogue convincingness!

A few years ago, Simon Martin made a film of a perfect CGI frog (Untitled. Strawberry Poison Dart Frog: Demuxed, 2008–11), which just sat there and breathed, shuffled its legs, never showed off, never demonstrated its capacity. Most new films employing cgi tend to be hysterical in their use; they can’t help but perform their own demo mode.

There’s an apocryphal story about someone who used to play Quake 3 when it first came out. He had set up an internal network for the game, and had left it running for a decade or so with a load of ai bots playing one another. When he went back to it, all the bots he had left to kill one another were just standing there. As he walked his avatar around, they all turned to watch him. He posted this on a forum, asking what he should do. After some cajoling, he fired a shot at one of them, and they all immediately turned and killed him. The idea that they’d worked that out! ‘Why are we killing each other when we could just do nothing and simply exist!’