Henrik Olesen

Studio Voltaire, London, UK

Studio Voltaire, London, UK

In Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1976 film Chinese Roulette, Angela, the family’s crippled daughter, initiates an uncomfortable truth game which forces her family through a series of painful revelations and accusations. This tense and ever-shifting dramatic triangle found echoes in the tentative choreography of objects and printed material gathered in the first solo UK exhibition by Danish artist Henrik Olesen. Engaging an unusual variety of narratives between the works on display, ‘Studio Voltaire presents Mr. Knife and Mrs. Fork’ set the scene for a family drama in which themes of identity, sexuality and reproduction were played out through a series of site-specific works and text-based collages.

Olesen’s subtle architectural interventions and slipshod sculptures subvert the accepted conventions and spaces of display; their ‘almost-not-there’ presence encourages the double-take as a mode of critical viewing, a means to re-inscribing the homosexual body into these spaces and the historical narratives they promote. Here the boxing-in of the stairs which lead down to the exhibition space, and the placement of a discarded sports sock beneath them, at once conjured and queered the spatial interventions of first-generation Conceptualists such as Vito Acconci, Bruce Nauman and Michael Asher – a decidedly heterosexual milieu which Olesen has previously re-interpreted according to narratives of alternative sexualities in his essay ‘Pre Post: Speaking Backwards’ (2006).

In the past, Olesen has used dumb, appropriated forms as stand-ins for personae. Here, a freestanding two-by-four was deictically transformed, by means of a handwritten inscription, into a proxy for (or a portrait of) the artist’s mother. A similarly fabricated paternal portrait stood, somewhat ruefully, in a nearby corner; split in the middle and supporting a precariously balanced empty chutney jar, these quizzical combines establish a porous, destabilized vernacular shaped by the various psycho-sexual or historical readings we choose to project onto them. I stared for an inordinate amount of time at an empty cardboard Doritos box, which contained the exhibition’s supposed guests of honour (a metal knife and a plastic fork accompanied by a jar of chocolate spread); Olesen encourages us to look for these alternative narratives in everyday objects.

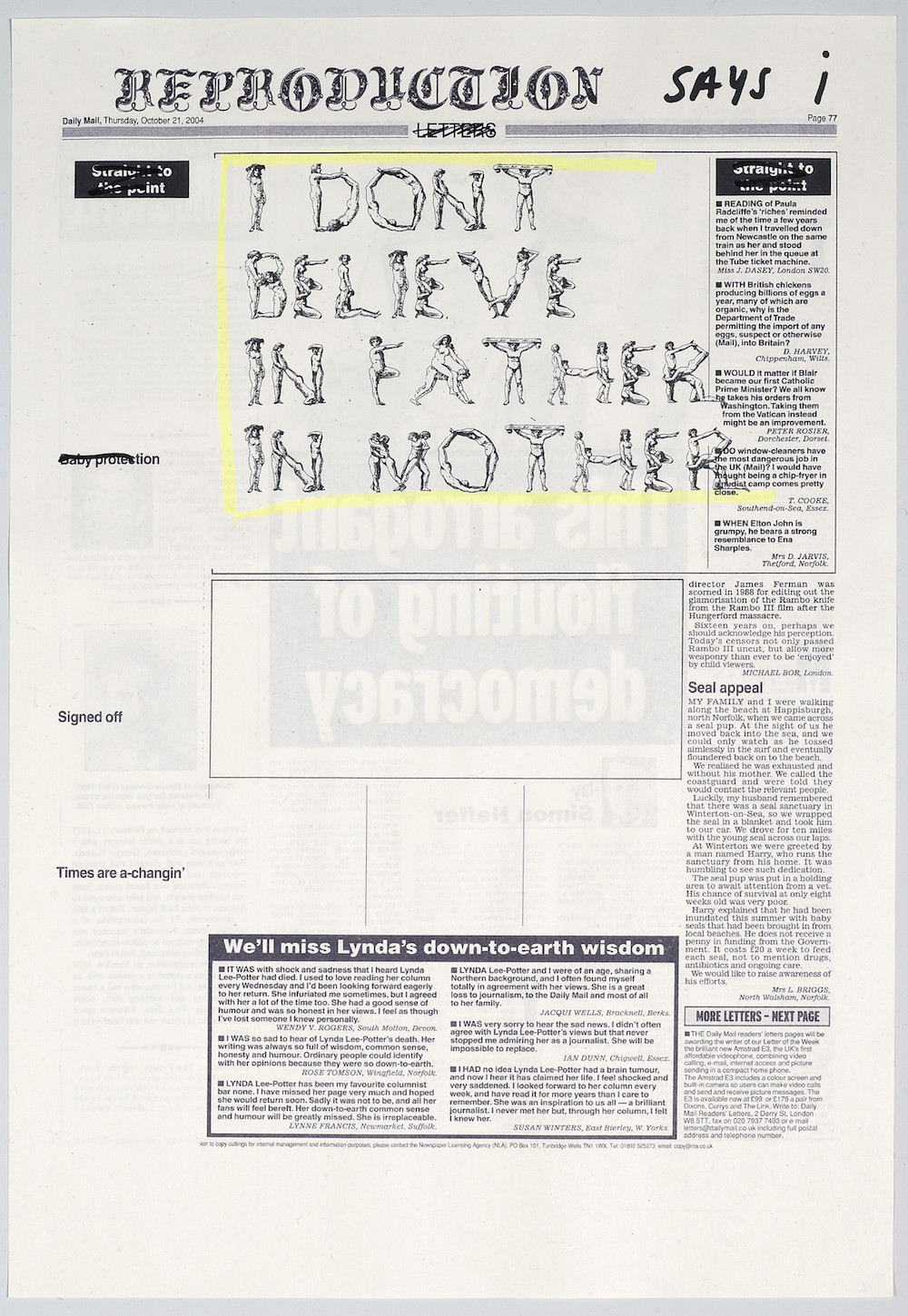

Placed emphatically at the centre of the installation in orderly grids across four tables, the 32-page collage series ‘Papa-mama-Ich’ (Father-mother-I, all works 2009) confronted the attendant parental entourage. Comprising a lengthy poem – disjointed in its appropriation of various quotations – digitally superimposed onto pages taken from the Daily Mail and the Daily Express, it is an elongated farewell to the narrator’s mother and father. Set in various typefaces, the text runs across the surface of the newspaper print, which, according to Olesen, babbles along in the background ‘like an annoying neo-liberal noise that never disappears’. Developing his language of textual intervention – seen in previous projects such as Manipulating Media (2002), in which stories of homosexual sub-cultures were mischievously inserted into the pages of the same right-wing rags, and Anthologie de l’amour sublime (Anthology of Sublime Love, 2003), in which images of sadomasochistic gay sex were spliced into Max Ernst’s La Femme 100 têtes (The Woman with 100 Heads, 1929) – ‘Papa-mama-Ich’ imposes a more evidently intrusive narrative which rejects the nuclear family and the normative relationships enforced by its structure. Sexuality and parricide have long been inextricably entwined bedfellows; here parental disavowal gives rise to an image of a self-producing body, or references to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s ‘Body without Organs’ (‘No Father, No Legs, No Arm No Feet No Eyes No Belly No Thumb No Elbow No Fist No Finger No Buttocks No Hair No Anus’, Olesen’s text rails), that eschews the dualisms of Western culture and sex as a means of production – a rejection cemented in the poem’s closing lines in which Olesen reworks Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine’s ‘Sonnet du trou du cul’ (Sonnet on the Asshole, 1872). Olesen’s shift from reproduction to self-production rejects the so-called natural in favour of a sexuality that is deliriously disruptive.