How Joyce Pensato (1941-2019) Captured the Junky Underbelly of Pop Culture

Gilda Williams pays tribute to the American painter, ‘an artist exalting in unruly triumph’

Gilda Williams pays tribute to the American painter, ‘an artist exalting in unruly triumph’

Painter Joyce Pensato spent most of her life within blocks of the Brooklyn street where she grew up, working in semi-obscurity some decades before the neighbourhood turned remotely hip. Long admired by fellow painters such as Christopher Wool, Pensato only gained wide recognition in the mid-2000s for her dripping portraits of Felix the Cat, Batman and Groucho Marx, all staring wide-eyed and menacing from immense, mostly black-and-white paintings. In Pensato’s hands, Homer Simpson or Daffy Duck seemed to reveal themselves as closeted bipolar sufferers: hostile in one canvas, catatonic in the next. Although her unruly paintings and drawings could initially seem to be the angry scribbles of some gargantuan toddler, closer inspection revealed the sophistication of their making. Encased within the sturdy cartoon-based outlines, her technique shifted seamlessly from the black-on-white mark-making in, say, the downturned line of Donald Duck’s deeply frowning bill (Little Lupe Donald, 2016), to the white-on-black overpainting or erasure that formed the flabby curve of Woody Woodpecker’s middle-aged beer belly (The Face Down, 2008).

‘For the longest time I’d been torn, divided’, Pensato once said. ‘I had two sides of me as an artist, and I was longing to just become one, totally unafraid of who I wanted to be’. Pensato’s autobiographical accounts described an ongoing struggle to reconcile her alleged contradictions: an attraction to the junky underbelly of American popular culture alongside refined painterly skill; a desire to work at tremendous scale alongside a talent for graphics and precise drawing. Perhaps it was her attempts to suppress her own unkempt nature that allowed Pensato to envision the dark secrets of her characters: Lisa Simpson’s latent manic aggression, Mickey Mouse’s unseen fury and frustration.

How out-of-sync the mess-loving Pensato must have felt amidst the perfect-housewife ideals of womanhood that were touted in America during the 1940s and 50s of her youth. Her Sicilian-born father was a kind of outsider artist himself, while her Italian-American mother thought art was like dirt, dragged uninvited into a clean house, as Pensato once said. Her teacher and mentor at the New York Studio School, Joan Mitchell, demanded that her pupils choose between French painters’ airy colour and the Germans’ lightless expressivity. Pensato’s painterly finesse prompted her to choose the French, but she fretted secretly that she might belong in the dirtier German camp. In fact, her art-making adhered to both, and her work developed schizophrenically along parallel lines, producing big abstract landscapes alongside simple charcoal drawings. The last-minute cancellation of a planned show at fabled Lower East Side gallery Fiction/Non Fiction in 1991 left her wounded and directionless.

Pensato credited Parisian gallerist Anne de Villepoix for spotting, in the mid-1990s, the potential for her cartoon-like paintings, which were later collected by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, among others, and in 2012 earned her an Award of Merit Medal for Painting by the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Pensato’s inspiration was drawn from her warehouse-sized collection of toys and knick-knacks: clusters of cross-eyed Cookie Monster dolls; vintage clown masks; broken Sponge Bob egg timers; South Park stuffed collectibles, ad infinitum. Pensato was delighted when her New York gallerist Friedrich Petzel suggested displaying portions of her paint-splattered figurine collection alongside her finished canvases in the 2012 exhibition ‘Batman Returns’, a tactic she repeated in London at her 2014 Lisson Gallery show, ‘Joyceland’, and elsewhere. Pensato seemed to cherish any means that stitched together her seemingly disparate sides.

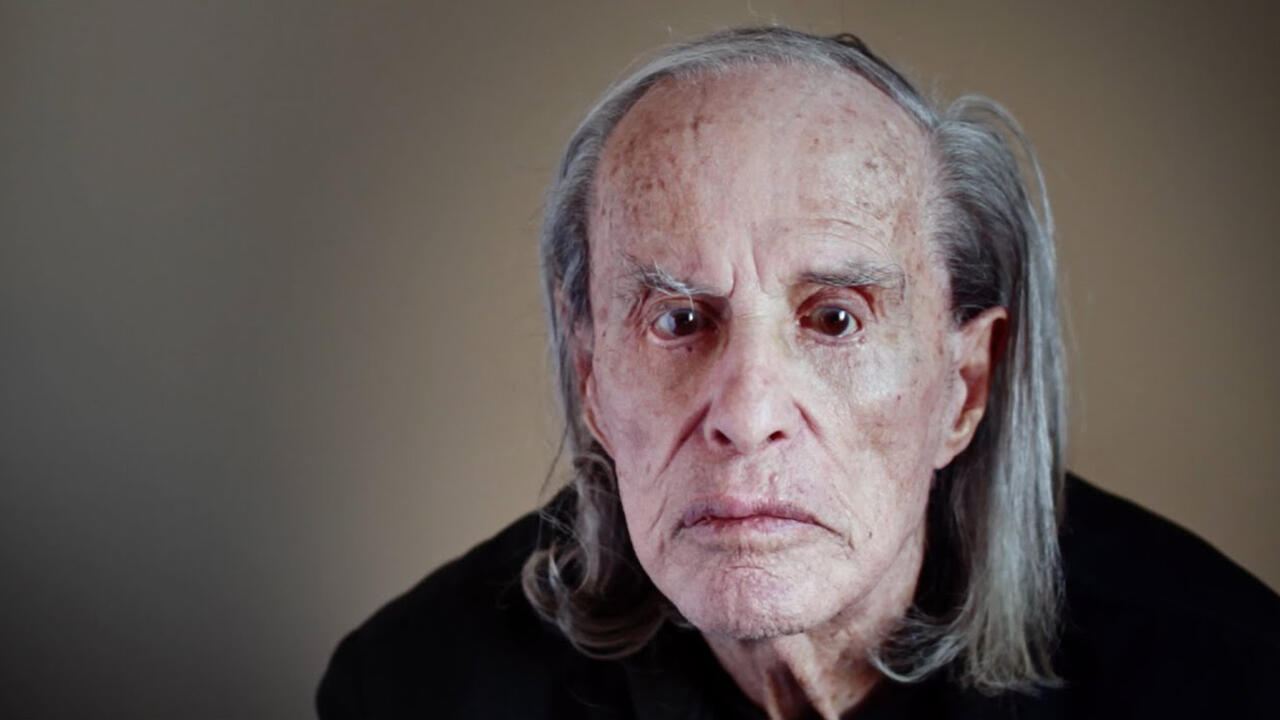

I met Pensato only once, for our ‘In Conversation’ at the South London Gallery last Autumn. I found her warm, uninhibited, sisterly and appreciative. She seemed happy, if surprised, by the packed youthful audience who connected her art to 21st-century practitioners such as KAWS. She openly admitted to the still-new sensation of travelling in comfort, no longer needing to count her pennies after a lifetime of financial struggle. Late photographs of Pensato show her smiling broadly in the unapologetic clutter of her studio, wearing immense reflective sunglasses that Elton John might have rejected as oversized and garish, her voluminous blonde frizz flying in every direction: an artist exalting in unruly triumph, amazed and rejoicing to finally be working and surviving exactly the way she pleased.

Main image: Joyce Pensato. Courtesy: © the artist and Lisson Gallery, London