Pandora's Box

Rediscovering Jo Bondy through her assemblages, box works, and ceramics from the 1960s to 1970s

Rediscovering Jo Bondy through her assemblages, box works, and ceramics from the 1960s to 1970s

In her 2010 Artnews article, ‘Where Are the Great Women Pop Artists?’, Kim Levin explored the divergent, gender-dependent nature of the movement: ‘Pop art in the hands and minds of women artists is intricately linked to the rise of feminist art, political and sociological art […] pop art in the hands of male artists was cartoony, exaggerated […] Involved with male sexuality, it had to violate something […] fast foods, fast babes [… whereas] Women’s Pop-related art had its own intentions […] Usually it opposed or dissected the male gaze.’ Levin’s argument – emphasized by its nod to Linda Nochlin’s infamous and important 1971 essay, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ – can be seen to embody the concerns of feminist or revisionist art histories, and the rediscovery and reassessment of excluded and forgotten women artists. Jo Bondy is one of these. Born in England in 1937, Bondy’s parents were refugees from Nazi Germany. She studied at St Albans School of Art, north of London, in the late 1950s and spent much of her life as an art teacher. Bondy died in 2015, and her collection was inherited by one of her former students – Stephen Rothholz. In collaboration with England & Co gallery, a body of work from the 1960–70s was exhibited during the first week of November in a temporary project space in Bloomsbury.

Bondy’s assemblage sculptures, box-works, and ceramics explore gender, sex and representation in various guises. It can be productively read through Levin’s appraisal of a critical, female-driven pop art, and in tandem with the European lineage of Pauline Boty, Kiki Kogelnik, and Evelyne Axell. This tongue-in-cheek approach to pop is perfectly exemplified by Boty’s final painting, Bum (1966), in which a women’s naked bottom is framed by a cartoon-like proscenium arch. The relationship between the box-form, found objects, and the human body in Bondy’s work could also be aligned with other international artists such Marisol and Dorothy Iannone, or even Nicola L’s Little TV woman: ‘I Am the Last Woman Object’ (1969), in which the artist imagined the female body as a functional domestic object: a cabinet. In Bondy’s drawings, breasts and buttocks abound – often coquettishly disguised as hearts, or peaches. In others, landscapes or tree branches fade into the shape of vulvas, evoking the sensual, erotic sketches of Judy Chicago. However, Bondy’s representations often drew on bawdy humour. The mannequin’s sheer pink knickers in Torso Box (1970) are stuffed with shredded pictures of men, escaping the seams like pubic hair. In her Violin case sketches from 1978, male and female bodies are delineated within the cases. In Violin case I, there is a deliberate play on the notion of a male ‘fiddler’, his arm poised ready to ‘play’ the female-bodied violin. However, the image of man ‘playing’ woman is disconcerting too, underlining the latent feeling of misogyny and female objectification that permeates much of Bondy’s work.

Looking further back into the history of art, there are also clear parallels between Bondy’s deployment of voyeurism and iconography of fetishism with surrealism and the avant-garde. Joseph Cornell, one of the most renowned box-assemblage artists, was heavily influenced by surrealism. ‘To watch a group of museum-goers gathered around a series of Cornell boxes is to observe public voyeurism,’ wrote Mary Ann Caws in 1993. ‘They have that same guilty look of pleasure as those who draw themselves up to the holes in the door of Marcel Duchamp’s Given (Étant donnés).’ Bondy’s boxes are exhibited with their doors shut; the surprise element of opening them becomes an essential part of their function. This guilty voyeurism is key to Bondy’s Wunder Box (1977). Opening the French doors (complete with doily-like curtains) reveals the exterior of a house and, through another window, a man and woman can be viewed engaged in coitus. While the majority of the man’s face and body is depicted, the woman’s identity is limited to stomach, thighs and genitals, almost perfectly replicating Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde (1866).

One of Surrealism’s enduring influences on women artists was the interrogation of fetishistic spectatorship, particularly the subversion of the image of the objectified female body as ‘Other’. Academic Susan Sulieman has referred to this technique as a form of ‘double allegiance’, serving to undermine and destabilise misogynistic visualizing practises rather than reinforce them. Bondy’s Hunter’s Box (1976) is the most overtly brutal. The box itself appears to converge the structure of a grandfather clock with the head of hobby horse. When the tower door is opened, it reveals a naked, blood stained female body in the recess, strung up like a hunted fox, with the fox’s brush affixed to the inside door. In an astute, visually evocative critique, fox hunting is equated with socially sanctioned violence against women.

Bondy’s large box-works are very theatrical, akin to stage sets. The attention to detail and the development of fabulist narratives is apparent in rich and fecund works like Untitled (Spider’s Web) (1969) and Drinking Water (1970s). Spider’s Web brings to mind André Masson’s 1937 Surrealist mannequin: Head in a Cage, the woman’s figure framed by its entrapment. It is interesting to also think about Masson’s sculpture in relation to the feminist art coming out of the United States in the 1970s. In Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s infamous Womanhouse (1972), a female mannequin appears held hostage by the ‘Linen Closet’. In Europe in the late 1970s, artists like Birgit Jürgenssen and Helen Chadwick photographed themselves wearing kitchen appliances they had built, such as stoves, fridges, and washing machines. Bondy’s female bodies, too, are often fragmented, either disembodied heads or headless mannequin torsos. Mirrored glass, netting and cut out panels are favoured materials and techniques, both reflecting and distorting reality. In Untitled box on a romantic theme (1977), a mermaid figure lies frozen under a sheet of transparent blue plastic. These works can be read through the use of symbolism in fairy tales, or even the spiritual image of Mother Nature. In the smaller assemblages, toadstools, snakes, flora and fauna recur. The evident relationship between Bondy’s work and the symbiotic lineage of surrealism and pop, combined with the politics of second-wave feminism and artistic practice, is a testament to the importance of her work within British art history. Marginalized for decades, Pandora’s box has finally been opened. Let’s keep it that way.

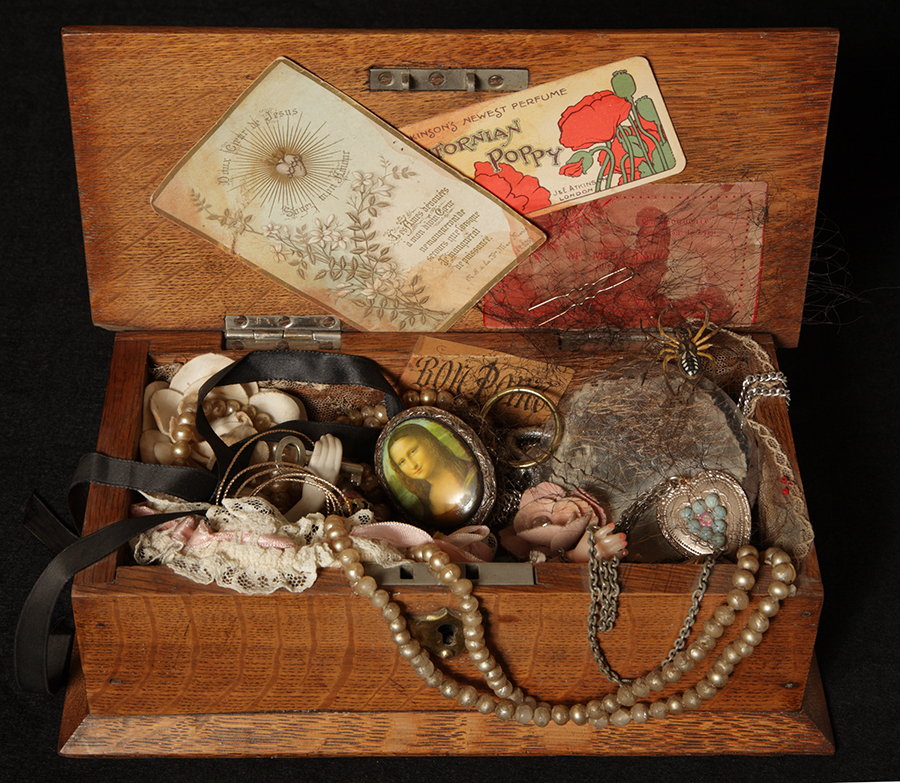

Main image: Jo Bondy, Wunder Box (detail), 1977, mixed media box construction. Courtesy: England & Co, London