Portfolio: Aaron Angell

With his current solo show on at GoMA in Glasgow, the artist shares a selection of influential images

With his current solo show on at GoMA in Glasgow, the artist shares a selection of influential images

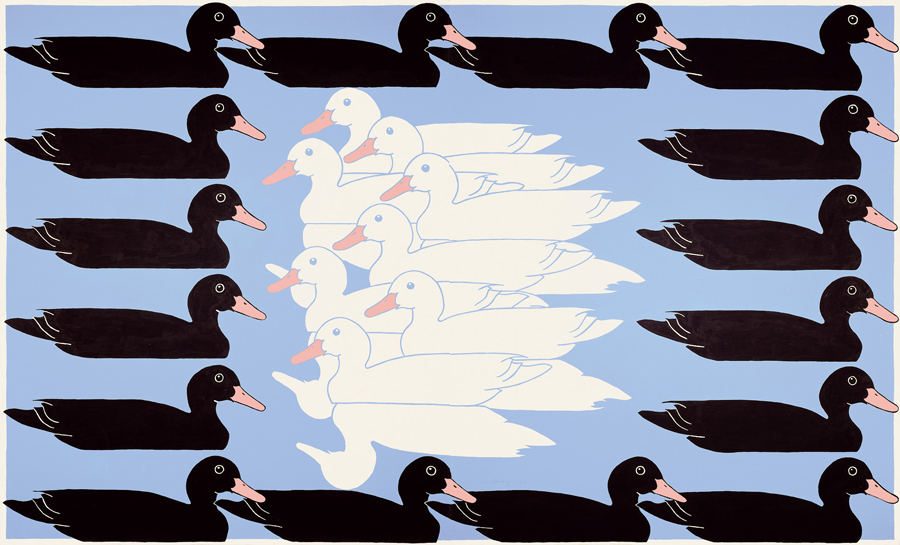

John Wesley : Untitled (ducks)

There is a germ of an idea in this image but it’s really about the oddness of vision versus reality. John Wesley is probably my favourite living image-maker. When you see his works in real life, texturally-, ‘painterly’-speaking, there’s almost nothing there – not even the fetishistic flatness of mechanically produced pop. It is as if they lose something on microscopic examination which only serves to further their importance as perfect, whole, irreducible images. This is my favourite painting of his. Like many of his images it is a magic piece of composition within the quasi-religious bounds of a premodern hierarchical perspective. I recently read Leonard Goldstein’s The Social and Cultural Roots of Linear Perspective (1988) and I am interested in the fact that images depicting linear projection sprung from and contributed to the understanding of the political and mechanical systems of which people were part, whereas their precursors – hierarchical projection, vertical projection, simple maps, calligraphy etc. – were more about depicting a moveable system of spiritual or social values. A distant church is larger on the plain than a mill in the foreground, if the former is psychically heavier than the latter.

Nigel Coates, Model for ‘The Wall’, Tokyo

This is on permanent display at the V&A in London. It is a model for a (realized) facade for a shopping centre in Tokyo. Nigel Coates designed it to look like a Roman wall which is permanently under construction. I like it because it seems to me to question the idea of the activation of buildings; whether this lies with the end users or its inhabitants, or with the people who are making the building, at the point(s) of making it. Picture the great ‘Dom’ of Cologne under construction: writhing with pulleys, people, painters, plasterers exploring the building haptically as they make it. All of them sweating and swearing in knots so entangled they can hardly be expressed. Contrasted with the finished structure, just this big dead thing like a head full of air, impossible to clean, unable to be properly touched, underactivated.

Pelecyphora aselliformis

I think about non-human minds a lot but especially those of plants, which are long, diffuse minds spread out over time, soil, wind, and the bodies, minds and mechanisms of other animals. This plant is Pelecyphora aselliformis from my own collection. It is a rare high-altitude cactus which is extremely slow growing. It has evolved to look like it is permanently swarming with woodlice possibly as a signal to attract pollinators.

Thomas Guest, Grave group from a surface interment at Winterslow

This amateur effort from sometime-archaeologist Thomas Guest recognizes the spiritual importance of the objects it displays in a way that is both romantic and scientific. It centres on a random selection of grave goods found in a barrow in Wiltshire in the south-west of England, placing them large as a planet at the centre of the composition. It seems to acknowledge that the truth of an inhabited terrain is often found poetically by digging, scouring, exploring its grammar, rather than by a Godlike depiction of its entirety.

‘Iron mallet’ teabowl, Japan

This teabowl or Yunomi is a really good example of this kind of recurring, hypertrophied form of rustication which is common in Japanese ceramics from this period. They are some of the earliest works I think to exploit irony, even via the slightly silly metaphorical names that were given to them like ‘Iron Mallet’, ‘Discarding Avarice’, etc. This one is trimmed with an extremely deep-set foot, making it look like a little hovering stone. It is glazed with a classic iron-rich Temmoku glaze but has been pulled from the kiln at a high temperature, causing it to cool very quickly. Gesturally this is similar to a blacksmith quenching a sword. this process is called seto-guro or ‘extraction black’. It’s sort of the only way to get this really nice but subtle black orange-peel effect. I like the hidden labour and knowledge that is behind the slightest but most exquisite of gestures in ceramics. It is almost a private language.

Aaron Angell's current solo exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA), Glasgow runs until 18 March 2018.

Main image: John Wesley, Untitled (Ducks), 1983 acrylic on paper, 90 x 150 cm. Courtesy: Fredericks & Freiser, New York and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles