Postcard from Barcelona

Protests against housing inequality, tourism and a colonialist past have been roiling across the Catalan capital

Protests against housing inequality, tourism and a colonialist past have been roiling across the Catalan capital

In the Terminal 1 baggage reclaim area of Barcelona-El Prat Airport, synthetic tones drift over slowly unspooling chords, stretching out the dreamy mood of post-flight proceduralism. Nearly four decades after releasing the seminal Music for Airports, Brian Eno’s impeccable sound design graces the physical infrastructure of Barcelona’s booming tourist economy, welcoming visitors with the inviting textures of his most recent project, Reflections.

Eno’s trademark sounds seep further into the city’s core by way of the contemporary arts centre Arts Santa Mònica which currently hosts his retrospective ‘Lightforms / Soundforms’ exhibition. Along with older work like his iconic generative installation 77 Million Paintings (2006), it features a piece specifically created for the centre’s Cloister Max Cahner called New Space Music (2017). Beneath a grid of blue and green lights, visitors are immersed in a pool of undulating pads as the space’s deep natural reverb blends stray notes into slowly decaying harmonies. The heatwave smothering Barcelona makes it virtually impossible not to sink into the sofas, but the stillness inside the cloister contrasts with the movement outside.

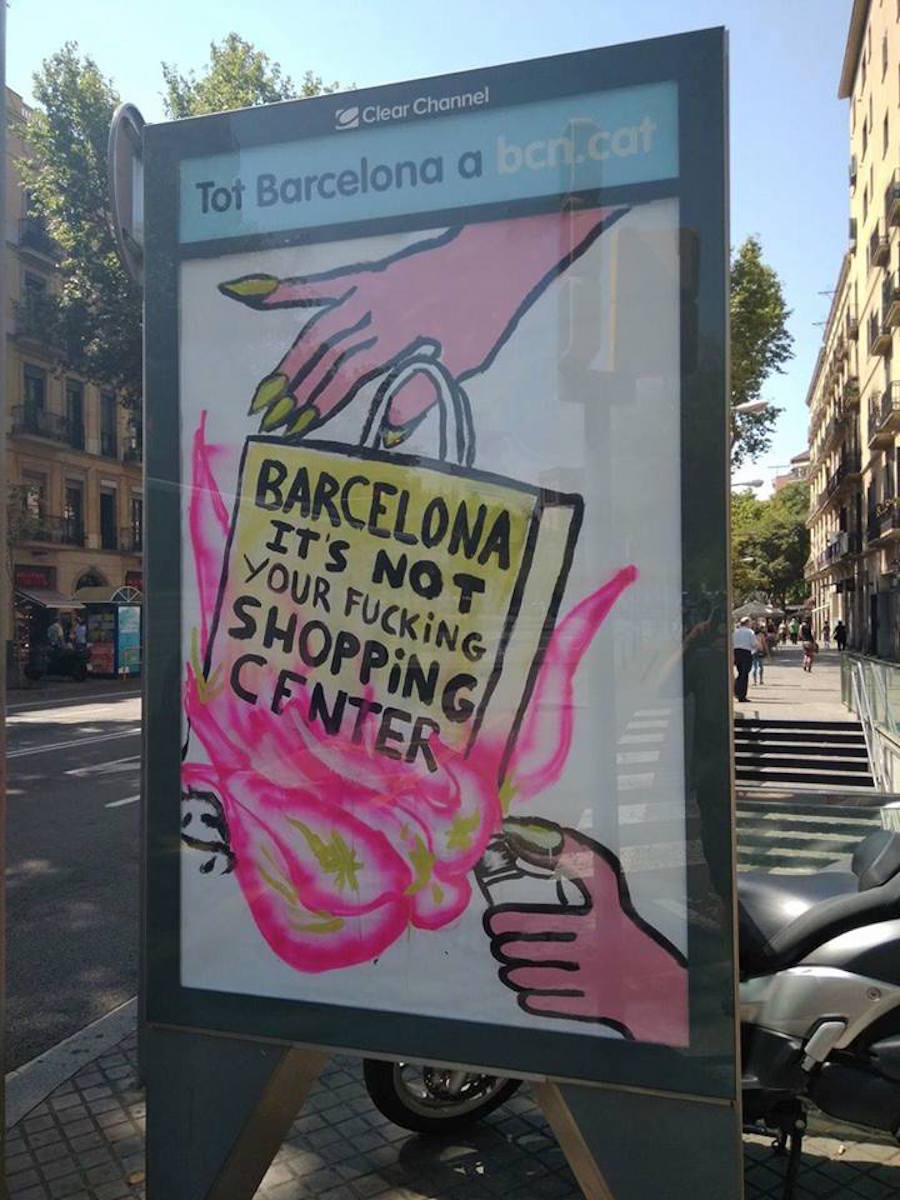

Meanwhile, on a billboard near the Plaça Universitat metro station, hot pink flames engulf a bright yellow shopping bag. Hanging from a crudely painted hand spiked with long, yellow fingernails, the bag is adorned with a declaration in English: ‘Barcelona. It’s not your fucking shopping center.’

For city councilman Alfred Bosch, the advertisement was just one more example of radical leftist mayor Ada Colau’s anti-tourism agenda. Shortly after seeing the image on Twitter, Bosch reprimanded city hall for allowing it to be displayed in a space granted by the municipality. The Catalan digital daily El Nacional then published an article about the advertisement under a headline that accused Colau’s government of promoting ‘violence against commerce’.

Of course, the municipal government had nothing to do with the advertisement. The Art Attax Bcn collective had slipped the poster into the display, as they did all over the city throughout June to kick off Barcelona’s tourist season. ‘They have accused our posters of being fake and violent,’ the collective states in an intervention titled #InvasionDelEspacioUrbano. ‘But aren’t all advertisements?’

Tourism and culture have been at the centre of public debate since Ada Colau’s Barcelona En Comú platform won the municipal elections in 2015. The summer prior to the vote was marked by intense protests against illegal tourist apartments in the Barceloneta neighbourhood. Several of the candidates on the En Comú ticket were prominent members of the neighbourhood associations that supported those protests and subsequently incorporated their demands into the campaign. Within a few short months of her mandate, Colau’s firm stance against the excesses of companies like Airbnb had become the subject of reports by the Guardian and The New York Times.

But the sharing economy’s impact on tourist apartments and the local housing market is just one part of the story. As sociologist Kevin Fox Gotham shows in Authentic New Orleans: Tourism, Culture and Race in the Big Easy (NYU Press, 2007), the displacement at the heart of protesters’ demands has less to do with the consumption preferences of individual tourists and more to do with how flows of capital in the real estate market shape urban policy in major tourist destinations. This was the major point driven home by former UN Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing Raquel Rolnik in her recent public lecture ‘Cities in the Hands of Global Finance’, given at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB). At several points, Rolnik made specific reference to the city’s expanding rent bubble and the struggles of the local housing movement.

Organized by the CCCB and the Barcelona Initiative for Technological Sovereignty, Rolnik’s talk was part of a year-long lecture series on technology, sovereignty and globalization curated by Evgeny Morozov. The timing of it could not have been more fortuitous. Two days after the lecture, protesters converged at the Plaça Universitat. From there, over 3,000 people wandered through the Sant Antoni, Poble Sec and Raval neighbourhoods, where rent rose by over 15% between 2016 and 2017. A portion of the route was led by a group of Sant Antoni residents, who marched through the streets in the sublime funereal style of a Spanish Holy Week procession, some holding papier-mâché vultures on sticks, others carrying a detailed model of a long-dormant, historic market: the Mercat de Sant Antoni. Stuttering snare drums punctuated the breathy vowels of an outraged saeta which spelled out a litany of property-related injustices.

The march was organized by the Barcelona No Està En Venda (‘Barcelona Is Not For Sale’) platform, which brought together several neighbourhood and community organizations as well as a recently formed Tenants’ Union. Along the way, they stopped at several housing blocks that had either been abandoned for years or were involved in major disputes between developers and tenants. Marches such as these, in which alternative and suppressed histories are plotted out against an otherwise anonymous urban backdrop, are a staple of Barcelona’s repertoire of collective action. In a city where, as Chris Ealham recounts in Anarchism and the City: Revolution and Counter-revolution in Barcelona 1898-1937 (AK Press, 2010), governments have repeatedly tried to bury the fact that a major part of the social fabric has emerged from several serious attempts at anarchist self-management, memory is an incendiary thing.

The local history of colonial violence is even more taboo. In his exhibition ‘Y tú, ¿por qué eres negro?’ (‘And you? Why are you black?’), photographer Rubén H. Bermúdez confronts viewers at the CaixaFórum center by surrounding them with images of anti-blackness in popular media and juxtaposing them with personal photographs. Stitched together with subdued, minimalist text, Bermúdez’s emotive storytelling builds a queasiness that stays in your chest long after you’ve left the space.

Barcelona’s built environment compounds that discomfort. In 2015, Peruvian-born artist Daniela Ortiz led a march pointing out the city’s monuments to colonialism which concluded at the end of the iconic Ramblas, where Christopher Columbus stands atop a massive column pointing outwards, as indigenous people kneel beneath him. And earlier this month, several of the collectives who had organized that march gathered at a monument to former slave trader Antonio López y López to rename the plaza bearing his name. As an alternative, they proposed the name of Idrissa Diallo, a young man from Conakry, Guinea, who died in Barcelona’s immigrant detention centre under highly questionable circumstances in January 2012.

Calls to take down the monument to López y López are not merely fringe demands. In May, Colau’s city hall announced that they would indeed be taking down the monument, just as they’ve been working to remove the remaining symbols of General Francisco Franco’s dictatorship from public space. As has happened with many of their gestures regarding historical memory or cultural programming, they have been accused by opposition parties of reviving a culture war.

But if taking down monuments to slave traders and fascists is the revival of a culture war, what do we call imprisoning artists for their tweets and lyrics? Recently, the Majorcan rapper Valtonyc was sentenced to three and a half years in prison for insulting the King of Spain and promoting terrorism in his songs. He is not alone. Cesar Strawberry, of the popular Spanish rap-metal band Def Con Dos, is also facing jail time for his tweets. So is Cassandra Vera, a 21-year-old writer known for her dark sense of humour. All of these sentences were enabled by the so-called Gag Law, which took effect in 2015.

To confront this censorship, the No Callarem (‘We Will Not Be Silenced’) platform organized a free, all-ages music festival on the weekend before Primavera Sound was scheduled to officially inaugurate tourist season. Under a blazing afternoon sun, thousands gathered in neighbouring Badalona at the Parc del Gran Sol de Llefià. After a ramshackle set of poetry and heavy psych played like free jazz, the event’s organizers stepped onstage to lead the crowd in a massive act of self-incrimination. One by one, they read the tweets and lyrics for which Valtonyc, Cesar Strawberry and Cassandra Vera had been sentenced. Nearly 4,000 people matched them word-for-word, making the phrases theirs. We are all guilty now.

Main Image: Pages from Daniela Ortiz, The ABC of Racist Europe, 2017. Courtesy the artist