Scenes of the New Jim Crow

In a survey at Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans, photographs by Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick capture life within the US prison industrial complex

In a survey at Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans, photographs by Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick capture life within the US prison industrial complex

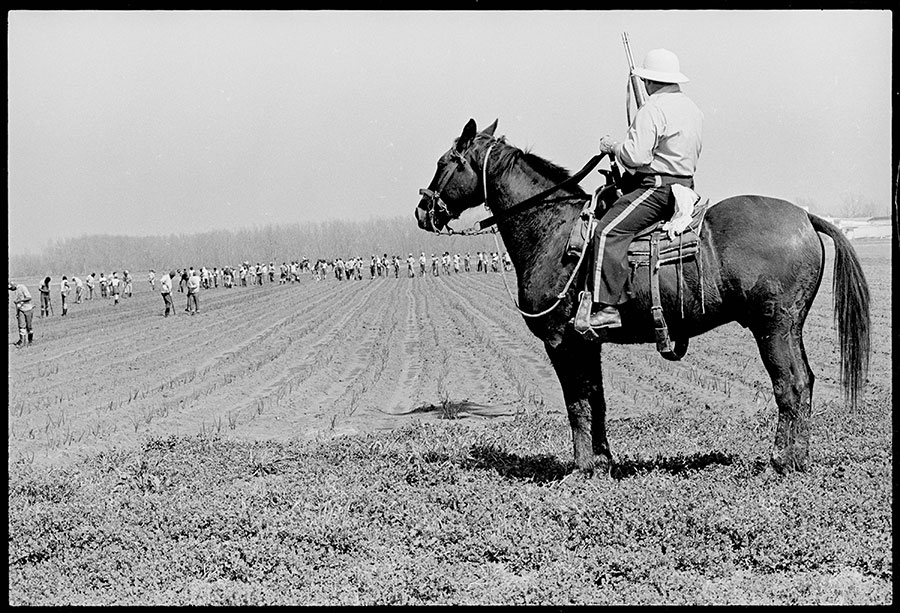

We’re in a field of neatly tilled rows, baking under the afternoon sun. In the photograph – a grainy black and white snapshot – the horizon line, slightly askew, is marked first by a row of trees, and then by a long trail of workers, hoes in hand. Too small to fully make out, their skin is dark, their jumpsuits brilliant in the daylight. In the foreground, a rider on horseback looms large in a Pith helmet and khakis with his rifle cocked at the ready. We could be on a slave plantation in the years before the American Civil War, but Keith Calhoun captured the scene in 1980, when he first started visiting the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola with his partner in art and life, Chandra McCormick.

Calhoun and McCormick – or Keith and Chandra, as their subjects know them – grew up together in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans, a historically black neighbourhood bordered by levees. Calhoun taught McCormick how to use a camera and develop film more than 40 years ago; since then they’ve been capturing rich tableaux of New Orleans, from its brass bands and jazz funerals to its dockhands and line cooks. They almost always shoot as a pair, offering advice or criticism, pointing out interesting scenes, making subjects feel comfortable in front of the camera. Though their joint CV is long, their inclusion in ‘All the World’s Futures’, curated by Okwui Enwezor for the 2015 Venice Biennale, led to a busy past few years – culminating in a survey at Art + Practice, Los Angeles in December 2018 and another at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans (CACNO), which closes 10 February.

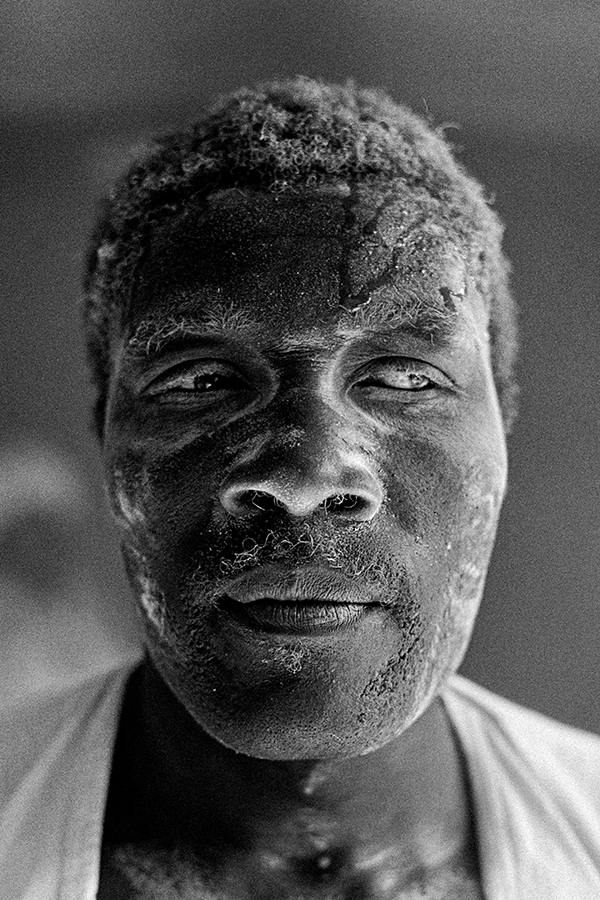

‘Labor Studies’ at CACNO focusses on Calhoun and McCormick’s many photographs of workers: intimate portraits of maids and cane cutters hang alongside snapshots of dockworkers collecting pay-checks or packing bags of sugar. (Most are untitled and undated: the artists’ archive is vast and disorganized.) Candid or carefully composed, neat or smeared with sweat, their subjects are always dignified. The artists’ proximity is plain to see – many of the images depict friends or neighbours – and distinguishes their work from documentary photography that traffics in archetypes. The stories on display are individual, even if together they form a raw and searing portrait of Black life in America.

That sense of intimacy stuns in Calhoun and McCormick’s most famous series, ‘Slavery: The Prison Industrial Complex’ (1980-ongoing), captured within the walls and fenced-in fields of Angola Prison. There is no joy to the labour in these scenes, but a sense of bearing witness to a crime. For those old enough to remember the halcyon days of the Black Panther Party, or those who grew up in the South, mention of Angola brings chills. With 6,300 prisoners on 18,000 acres, it is the largest maximum-security prison in the United States. Named for the former plantation whose land it occupies, which in turn was named for the land from which the ‘most profitable’ of its enslaved labourers were kidnapped, Angola is a chilling symbol of what legal scholar Michelle Alexander has called ‘the New Jim Crow’: a system of mass incarceration that strips mostly black prisoners of their rights and forces them to work on prison farms and factories for little or no pay. Of course, this system isn’t new at all, but a vestige of the slavery the ‘Jim Crow’ laws were crafted to replace: the 13th amendment to the US Constitution, passed in 1865, outlawed slavery ‘except as punishment for crime’. Government-sanctioned slavery means punishment for profit, a prison industrial complex with in-built racial bias and little economic incentive to reform itself.

Calhoun and McCormick’s Angola photographs capture many aspects of life at the penitentiary. Inmates till fields and pick cotton in the presence of armed guards; they pose behind bars, march down rows of barbed-wire fencing. Many images document the Angola Prison Rodeo, in which stripe-suited prisoners compete to tame bucking bulls for an audience of largely white tourists – a brutal reprisal of Roman gladiator contests. (Tickets for the The Wildest Show in the South, as a 1999 Academy Award-nominated documentary called it, go for as little as $20 – the proceeds of which fund religious educational programs.) One photograph shows a crowd of black inmates, wearing stripes, sitting in a kind of ‘bull pen’ as if awaiting their turn for slaughter.

Decades of access have meant that Calhoun and McCormick are often their subjects’ only link to the outside world. That has included many political prisoners – former Black Panther Party members, convicted on often specious charges – among them the Angola 3, who were sentenced together to the longest terms of solitary confinement in US history. (The last to be freed, Albert Woodfox, left Angola only in 2017, after 43 years in ‘the hole’.) If the artists bring information in, they also carry it out with them, and education remains a central priority of their practice. In 2007, the two founded the L9 Center for the Arts in their Lower Ninth Ward studio, where they give regular photography classes to neighbourhood children and encourage them to document their lives. ‘If you teach a kid that their life can be the subject of art,’ McCormick told me, ‘they begin to see that their life has value.’

When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005, the Lower Ninth levee ruptured, flooding the ward. News helicopter footage showed rooftops barely visible above the muddy brown water. Nearly 2,000 people died; some simply never returned. Today, there are empty lots throughout the neighbourhood where houses were destroyed by the storm or abandoned and razed by developers. Many of Calhoun and McCormick’s negatives, stored at L9CA, were ruined by the floodwaters, but the artists have chosen to see this as a blessing in disguise: what they did salvage and develop has been corroded, flecked like aging daguerreotypes, their borders stained bloody red and cool cyan.

It is a rare art that gives all and takes nothing in return. Such is the work of Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick, who have spent four decades documenting Southern Louisiana block by block and cell by cell. Their only demand is reform for a system that values Black lives less than others – one that fails to recognize the beauty plainly obvious in their photographs.

‘Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick: Labor Studies’ is on view at Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans until 10 February.

Main image: Keith Calhoun, Angola Prison, Men Going to Work, 1980, photograph. Courtesy: the artist