Sculptors Discuss Sculpture

Ten contemporary sculptors are asked about the ways in which they feel meaning is controlled and conveyed in their work

Ten contemporary sculptors are asked about the ways in which they feel meaning is controlled and conveyed in their work

Although much of your work might initially appear to have abstract elements, it was shaped by a narrative only you are likely to be aware of and is influenced by — and in some cases employs — found objects. To what extent is an understanding of the ‘back-story’ — i.e. the provenance of the ideas, objects or references to the body that might have influenced your work — important in terms of how it is read? Do you feel there is a right or wrong way of reading and understanding your work? To what extent do you like to control the meaning your work generates?

Leonor Antunes

I have used found objects in my work when I needed an element with a certain history, one with an irreplaceable presence. I made an intervention using a particular book that I carefully dismantled page by page. I then sent each page in the post to people I know from different contexts, all of whom are related to each other. I sent the pages from the location where the book was both written and takes place, and at the exact moment when the action begins. This remains exclusively in the field of action and in the relationship between the recipients of the pages; it cannot be reduced to a single object.

I have also been collecting Portuguese/Brazilian gold coins dating from the 18th century – they were minted during the colonization of Brazil. I then erased the image on the coin by melting it. This sculptural gesture is linked to the many ancient Greek bronze statues that have been melted down to recycle the valuable metal in times of war. A great part of its beauty lies in its imponderability.

I often refer to specific communal buildings or houses in my work; however, I never document these places, I only measure them. This process helps me to delineate the work I then make in terms of size, weight, mass and gravity.

I do not think in terms of creating something new, but rather use the past as a source for linking things together. Most of all I am interested in the idea of sculpture per se, which still operates as a very specific medium. The space it generates, between the viewer and the object, and vice versa – but then this is just a beginning …

Reading a work is about spending time with it. I believe both in the possibility of escape and of being present in a moment. I am interested in the materiality of the thing itself and the nature of its materials, how they behave and how they age. I also believe that looking at the work now is a completely different experience to the one it will be in 50 years; the leather will darken and wrinkle, rubber will shrink, metal will tarnish, and so on. One has to take care of it. I believe that the act of making is closely related to the act of caring. By subverting expectations you increase the chance of offering a more direct experience.

Leonor Antunes is a Portuguese artist living in Berlin, Germany. In 2011, she had solo exhibitions at: Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art, Porto, Portugal; Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain; Kunstverein Dusseldorf, Germany; and Museo Experimental El Eco, Mexico City. Her solo show at Marc Foxx, Los Angeles, USA, runs until 13 May, and her solo exhibition at Air de Paris, Paris, France will run from 1 June – 13 July.

Alice Channer

I certainly don’t see my work or any element of it as abstract. I don’t think that anything in the world can be. I’m trying to concentrate or pack as much as I can into it, and what’s important is that certain elements are present; I have no expectation that they will be read or understood in a particular way. I don’t think that art operates like the rest of visual culture, which often courts a particular interpretation in the audience of consumers it desires. Instead, I want to make art works and exhibitions that are beings in their own right, with layers and layers of being absorbed into them, some physical, some mental, some of which are immediate, others less so.

In three recent works, Cold Metal Body, Large Metal Body and Warm Metal Body (all 2012), I stretched massively distorted digital prints of classical drapery beyond the limit of the South London Gallery ceiling. As long as I have done my part of the work well, it doesn’t need to be made explicit that the particular classical sculptures whose clothes I stole are sea nymphs: embodied personifications of water made in hard stone. Because of the way the works are made and encountered, I can feel the changes in state between liquid and solid as I stand in front of them. I come to making art with a faith in the strange power of objects to hold all of this, and more, within themselves.

What I want from art is to feel another person thinking. It’s this kind of relationship with a group of objects in a room, arranged in a particular way and at a certain time, that I’m after.

I hope that my work can be generous because of a very different kind of precision. If there is a kind of meaning I am interested in, it is one that is distributed, shared, continually and often awkwardly renegotiated, and arrived at using both the body and the mind. This is why exhibition making, working with the way in which objects are experienced in real time and place, is crucial for me.

Alice Channer lives and works in London, UK. Her solo exhibition ‘Out of Body’ is at the South London Gallery until 13 May.

Thea Djordjadze

I really can’t tell how important the back-story is, in terms of understanding my work. Even if I begin with a narrative, the process of making a sculpture transforms it into something else. Sometimes a story that was important to me becomes uninteresting, or lost or forgotten (I am really into forgetting), and then a new narrative emerges. I like the possibility that someone with a completely different background to mine will interact with the work.

The back-story, if there is one, changes or transforms while I work in the space where the piece is going to be shown. I try to move the elements around the gallery until they come to rest in the position that they, or I, want. In the end, the narrative becomes an additional part of the sculpture, in a similar way a title does.

I don’t think there’s a right or wrong way of understanding my work. I have to control so many elements in it and still the unexpected appears and surprises me. I can’t control the meaning my sculpture generates; in fact, I refuse even to try.

Thea Djordjadze lives and works in Berlin, Germany. Her most recent solo shows were at Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo, Japan (2011–12); and The Common Guild, Glasgow, UK (2011). She will have solo exhibitions at Sprüth Magers, London, UK, in September; and Malmö Konsthall, Sweden, in November. Her work will be included in group exhibitions at ACCA, Melbourne, Australia, in August; and Museo Rufino Tamayo, Oaxaca, Mexico in November.

Liz Glynn

My work is dependent upon references that exist in the outside world; I can’t walk into the studio and arbitrarily make a sculpture. As my sources have become more densely layered, borrowing across different epochs from the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead to the recent financial crisis, the possibility of a viewer identifying every detail becomes more remote. Meaning does not rest in recognizing the source, but rather in tracing how it is deployed within a larger framework.

I have grown increasingly interested in the plasticity of historical narrative, and ideas of poetic truth over factual accuracy, such as 19th-century amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann’s desire to prove that the events in Homer’s Iliad actually happened through his excavation of Troy. In my work, ancient reference often functions as an allegorical decoy for contemporary concerns such as irreparable loss and irrational desire.

While historical narrative provides a structure for meaning, any encounter with an object begins with a visceral response. My initial induction into the cultural provenance controversies regarding antiquities was seeing a picture in ArtNews of a fourth-century gold funerary wreath that the Getty Museum had agreed to return to Greece. Without knowing about the controversy, my first reaction was: ‘I want that.’ This desire has a political dimension, for it has frequently justified breeches in the ethical guidelines governing museum acquisitions. The sculptures I make seek to provoke a similarly complex response: pleasure provides a point of entry, complicated by additional intellectual information that must be reconciled with the ineffable.

My work traces dynamic shifts in cultural value, and consequently I am not invested in creating a singular read of an object. Each work is intended to serve as a vessel for conversation, enriched by the viewer’s own knowledge, and contextualized in the present tense.

Liz Glynn lives and works in Los Angeles, USA. Recent projects include ‘Black Box’ as part of the Pacific Standard Time Public Art and Performance Festival, Los Angeles (2012); and ‘Utopia or Oblivion’ as part of Performa 11, New York, USA (2011). Her work will be featured in the Hammer Museum’s ‘Made in la’ biennial, Los Angeles, from 2 June – 2 September.

Charles Long

It’s brilliant timing to entertain this issue of ‘back-story’ and these questions of intentionally placed meanings and unavoidable misreading surrounding the making and viewing of sculpture – and yet also not-so-good timing (terrible, in fact, but I will get to that). This is an enigma I am in the very midst of solving through the creation of new sculptures that have successfully eliminated all content. Sculpture – presently a hair’s breadth away from being everything that has ever existed or can be thought of – has evidently become a yawning gateway for everything that can be expressed. The vastness of this portal can hardly be imagined, but, to give you an idea, consider that everything that has ever existed is linked in a chain end-to-end and eventually connects back to itself forming a giant ‘Super-Thing-Ring’ (str). This colossal opening is large enough to allow everything that can be expressed about those things to pass through, and when they do, each expression instantaneously reverts to a thing that is instantly sucked up as another intermediary link in the expanding str. You can see where this is leading – it’s pretty scary – but we see it happening from undergraduate critiques and all the way up the food chain to works made for benefit auctions.

OK, so why is it bad timing to address this issue? I am writing to you from the lobby of the Hotel de la Paix in Geneva, where the winds are blowing so hard off the lake (around 60 kilometres per hour right now) that the magnificent Jet d’Eau fountain just totally soaked me and fried my laptop as I was waiting for the bus. Now I have to use the computer in the lobby, so I’ll keep it short – it’s crazy in here. Basically, I have a grant to work here at cern using the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in making sculptures that have zero content and we had an accident. I was welding up a form, pretty much like the ones in my recent show at Tanya’s (Bonakdar), and a cryogenic magnet support broke during a pressure test involving one of the lhc’s inner triplet (focusing quadrupole) magnet assemblies, provided by Fermilab. No one was injured thankfully. but, I won’t have that piece ready for the art fair (thanks Fermilab!). I got an explanation from Fermilab director Pier Oddone who excused himself saying: ‘In this case we are dumbfounded that we missed some very simple balance of forces.’ Yeah, tell that to Tanya.

Charles Long lives and works in Los Angeles, USA. His public art work, Pet Sounds, will be installed this summer in Madison Square Park, New York, USA. Long’s solo presentation, ‘Seeing Green’, was presented in conjunction with ‘All of This and Nothing: 6th Hammer Invitational’ at the UCLA Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2011).

Christina Mackie

I don’t consider my work to be abstract; it all comes from my own life, the arc of which is the narrative. It’s a metaphysical space, peopled, full of furniture, personal stories and locations, which I use as a fuel cell to generate new meaning for myself. It works best if I ignore the possibility of the audience; a reverse suspension of disbelief. When I’m working I don’t consider what the reaction to the work might be.

All objects are more or less found; even a sheet of paper is a product. I am interested in what happens to materials after they’ve entered my zone of influence. I like to work in a free space where things can come together. Every idea and object has a history, which describes its provenance and tells you what its doing there. But you don’t need to know the history of an object or a person to have an insight into them, because everything is available at the moment when things are seen. There’s no point trying to tell every little thing because everyone reads things differently. The presence of an observer unavoidably influences the meaning of all objects.

I would like people to feel curious and unbiased when they look at my work, and to make their own associations and references. I prefer the constructive approach over the destructive. I can’t control how meaning is generated, but I can control the conditions that set things in motion. Once the work has entered the consciousness of the viewer, however, what they make of it is entirely out of my control.

Christina Mackie lives and works in London, UK. Her solo exhibition, ‘Painting the Weights’, which was first shown at Chisenhale Gallery, London, earlier this year, will open at Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, Denmark, on 25 May. She will be showing at Catriona Jeffries Gallery in Vancouver, Canada, in September.

Kilian Rüthemann

My work is made with simple gestures, which remain visible in the finished piece and can be traced back through the process of production. I want viewers to re-enact my gestures in their imagination and to feel the joy of, say, breaking glass or smearing Nutella on a slice of bread. I use familiar objects, materials or situations that people might have a sense for. I’m not hiding anything, so the back-story is always present in the work. Occasionally, I use titles to hint at the issues that I’m into, but they don’t have to be followed through to understand the work.

I try to be aware of all the subjects that my works generate; some may be of more interest to others than to myself, but that’s ok. There’s not too much to misunderstand, I think, but I’m always open to suggestions. Sometimes, someone puts my work into words I haven’t thought of, which might give even me a better understanding of it. I usually know what I want from my work and I try to make it visible. If you’re able to see it too, I’m happy. I usually only intervene with directing the meaning of the work – for example through a title – if there’s a real possibility of misinterpretation. I can control precise setting of the work; it’s an offer. I’m always curious to see what follows.

Kilian Rüthemann lives and works in Basel, Switzerland. His work is currently included in ‘Das Unerwartete erwarten’ (To Expect the Unexpected) at Künstlerhaus Bremen, Germany; and David Dale Gallery, Glasgow, UK, which is part of Glasgow International Festival (both until 20 May). His show at Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich, Switzerland, opens 13 December.

Karin Ruggaber

For my recent show at greengrassi, I worked from an image of a Jacquemart clock (Carillon du Mont des Arts) that is on a façade in Brussels. I am fascinated by the clock’s structure. Its strange and fictional figuration portrays the hours as statues of different historic citizens of Brussels in various poses – combining symbols, large numerals and an ornamental sun as the dial. The idea of this clock as an ordering system is interesting to me as it brings together stylized figuration, symbols and a circularity, all of which operate on the same flat mechanical plane. The clock’s attributes became a kind of template when making the reliefs for my show, but none of this is directly visible in the work.

I don’t provide this background information but I don’t withhold it when asked. There are many external references that come into the making of the work. These range from images of cooking and food preparation to architecture – for example, Roma villas or the buildings designed by Rudolf Steiner. This background material is abstracted into an invented materiality and form, which becomes very artificial and removed from direct representation. Occasionally there is a more immediate relationship where the images appear in books that I make, or become part of a show.

For some years I’ve been photographing buildings in a suburb of Istanbul and I have used one of these as the image for my invitation card. Its geographical location on the edge of Europe allows for an experience just outside of the familiar, which is something that I would like to convey in my work. I hope that it can retain a sense of the thinking that goes into it.

Karin Ruggaber lives and works in London, UK. She had a solo show at greengrassi, London, earlier this year and her work was included in British Art Show 7 (2010–11) and ‘Camulodunum’, Firstsite, Colchester, UK (2011–12).

Bojan Šarčević

Recently, astronomers detected signs of life on the moon. However, this ‘life’ wasn’t extraterrestrial but of the more prosaically earthly sort. When we observe the crescent of the moon, we might also notice also a grey part that is not lit directly by the sun’s rays. What illuminates that shady part is the sunlight reflected from the earth, which is loaded with information, taking on the colours of vegetation, clouds and oceans. The light records the signature of molecules in the atmosphere and becomes polarized. These phenomena are analogous to the provenance of artists’ ideas and references and, consequently, their interpreters.

Understanding the provenance of my ideas and sources shouldn’t be a crucial aspect of relating to my work. I try to leave my pieces as open as possible to various interpretations. I don’t search for, or try to impose, a finite meaning on a work as such, although I do expect an assertive clarity and precision in my visual expression. At the same time, it is inevitable that the context, the conditioning and the decisions made during the conception and realization of the art work will provide a framework for its reading. But this framework could be just a starting point for further thinking.

Misinterpretations can arise from inattentive and unimaginative perception, but that doesn’t mean they’re illegitimate. Like astronomers discovering ‘life’ on the moon, this doesn’t make me a proponent of correct interpretation but rather of a binding one, capable of attracting and holding. After all, as in science, it is the work stirring the meaning in its own direction.

Bojan Šarčević is an artist who lives and works in Berlin, Germany, and Paris, France. His solo exhibition, ‘A Curious Contortion in the Method of Progress’, runs until 6 May at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz.

Nicole Wermers

Although my work might appear abstract, it refers to concrete objects, the structures of everyday urban life (the gate-like security devices at shop exits, for instance) and fragments from lifestyle industries, such as magazine pages. I hope that while not all my references are instantly recognizable, most linger as an implied presence.

My work deals less with an actual narrative and more with how one might associate and interact generally with objects. The found object exists only as a starting point; the sculpture itself is a departure. Much of my sculpture exists on the threshold of the functional, indicating that a slight shift in either direction affects the status of objects.

For example, a recent series of sculptures ‘Wasseregale’ (Water-shelves, 2011–12) accesses a Modernist language as appropriated by an architecture of commerce which, once displaced, may seem abstract or formal, recognizable but not useful. What I find extremely interesting is the adaptation of fine-art aesthetics within the overall design of our daily lives and I want people to be aware that I am referring to both art history and to the ways in which it has been appropriated by consumer culture.

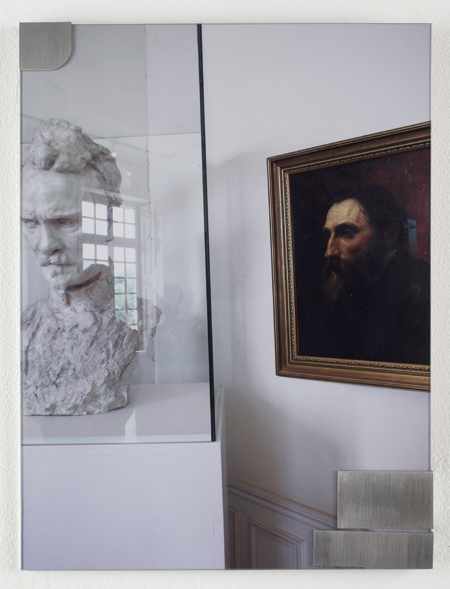

It is only recently that I have referred to something as particular as the Rodin Museum in Paris. Usually, I refer to specific but ubiquitous places and situations. I feel that there should be a level in my sculpture on which a piece just works and allows for a physical and structural reading.

Generally, I prefer the viewer to generate their own moment of realization or understanding of my works. I like to think of meaning as something that allows for some flexibility and that also may change with time. Ideally, I would like people to be aware of my previous work and to read individual pieces within that context. This should be sufficient.

Nicole Wermers is a fellow in residence at the German Academy in Rome, Italy. Her work is included in ‘A wavy line is drawn across the middle of the original plans’ at the Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne, Germany (until 10 June); and ‘Out of Focus’ at the Saatchi Gallery, London, UK (until 22 July). Recent solo shows include ‘Spray’ at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, USA (2012); ‘Hotel Biron’ at Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Dusseldorf, Germany (2011); and ‘Buhuu Suite’ at Herald St, London (2011).