Space Man

Annette Leddy explores how the late Fluxus member Robert Watts sought to bring the universe into the home

Annette Leddy explores how the late Fluxus member Robert Watts sought to bring the universe into the home

In the late 1970s, Robert Watts wrote the following advertisement to be placed in the classified section of an unspecified newspaper:

Wanted. One used space ship in good condition to accommodate 6 persons. Prefer maintenance-free craft with good electronics suitable for interstellar flight. Phone (215) 588–2721 after 6 pm.1

It might be seen as a characteristic attempt to create a small, amusing disruption in the infrastructure, like the erotic stamps Watts printed and occasionally used to send mail through the US Postal Service, or the hundreds of offset-printed etchings of dollar bills on which he altered the image of George Washington to suggest senility. However, this advert also signals a change in Watts’s practice: the moment he turned toward Conceptual work about outer space. At the same time, he retained what had been a primary interest of his since the early 1960s: objects of the home. In effect, in the 1970s he began to interpolate the universe into the home.

Watts – American sculptor and media artist, who died in 1988 at the age of 65 – is known primarily as a member of Fluxus. However, he also had an art practice and reputation quite distinct from Fluxus, and it is only by looking at the work’s evolution over three decades that one can grasp the artist’s achievement and his vision, some of which is solely accessible through his archive, with its amusing, visionary sketches. The corpus as a whole shows how Watts, who had degrees in both engineering and ancient art history, anticipated artists whose media is furniture and home décor, such as Robert Gober and Andrea Zittel. He also embedded in this work references to pre-Colombian cultures, evoking a comparison between past and present.

Watts’s early work is perhaps best understood as having participated obliquely in the 1960s Cold War design dialogue that began after the detonation of the atomic bomb, and that heightened with the launch of Sputnik in 1957 and the moon landing in 1969. Within these markers of unparalleled seriousness, designers and artists ruminated in different registers on the home for a range of reasons: amplified postwar commodity production; positioning of domestic space, especially the kitchen, as a site of East/West competition; and incipient changes in the traditional family.2

Throughout the 1960s, Watts created art about food, furniture, homewares and gardens. In pieces offered for sale as multiples, he deliberately scrambled his work’s use value and exchange value, as is demonstrated by a 1966 issue of The New York Times Magazine devoted to the home that features work from Herman Miller Studio and other top designers. Pop art and Fluxus pieces appear toward the back in a two-page spread titled ‘They Call it Art’.3 One of these pieces is Messy Desk, by Watts and Peter Moore, which consists of a photograph of disorganized piles and sheets of paper laminated onto a tabletop, which is in sharp contrast to the clean, efficient design on the magazine’s main pages. Like many of the multiples available through Fluxfurniture or Implosions, Inc. – such as Crossed Nude Legs Table Top, Dollar Bill Toilet Paper or Mirror Continuously Undulating – it functions as an ironic, even goofball, commentary on the Cold War commodity world.

Watts is most associated with a series of chromed food that he began in 1962 and that was shown, alongside work by Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg, in the landmark Pop art exhibition ‘The American Supermarket’ (Bianchini Gallery, New York, 1964): bread and butter, eggs, Swiss cheese, cabbage, sandwiches and fruit such as apples, cantaloupe or pears. These foods, along with others rendered in Perspex, felt and laminate, comprised the standard American diet of the 1950s and early ’60s, but it’s only by looking at the written list of objects that this historical menu emerges, because the chrome is otherwise so distracting that the food is altered from the condition of everyday comestible to the enshrined observable.

This de-familiarization enables a series of stunning oppositions with Cold War resonance. Their shine, for example, associates them with cars, rocket ships and money, and at the same time with the spectre of radioactivity. The eggs, in particular, among the earliest of Watts’s chromed food pieces, portend a disastrous future for the human species, recalling discussions of atomic fallout and sterilization of human and animal female eggs. On the other hand, the act of chroming preserves and even elevates them, like museum pieces or artefacts of our own civilization. A fusion of Pop object and Modernist design, they also repudiate both as insufficiently grave.

From the chromed food, Watts moved to laminated photographs of food, to furniture in the shape of food, and then much more extensively to the concept of furniture and homewares inspired by body parts, often photographed, laminated and encased in Perspex blocks. Chest of Moles (Portrait of Pamela) (1965/ 85) is one such work, but drawings suggest that Watts conceived a great many more ‘favourite spot’ pieces, including Side Belly, Tooth, Navel, Arm at Pit, Right, and so on. At least one of these works was imagined on a human scale. In Vulva Room, partitions within a room create a kind of shrine to a wall-sized, illuminated photo of the triangular pubic hair partially obscuring the female sexual organ.

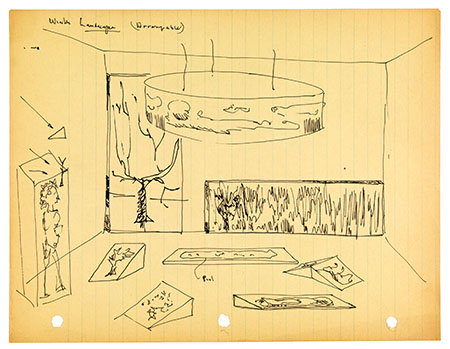

The next series Watts developed integrated natural cycles into the home, including phases of the moon and seasonal shifts. His drawings show that, beginning in 1965, he was thinking about interactive sculptures with titles such as Rearrangeable Landscape or Transformations of Seasons Garden or Winter Landscape (Arrangeable) in which he would photo-laminate and enclose in Perspex plants or other objects from nature, creating large pieces that could be moved around a living room as the owner/participant felt inclined to do. Or he thought of integrating sheets laminated with photos of the sleeper with the interior décor affected by season; on the wall above the bed would be two panels: ‘Cloudy’ and ‘Hazy’.

Of these ideas, Watts produced Three Clouds (1965) in which cubes of approximately one square foot are mounted on pedestals. On one cube are photographs of clouds, on another are photographs of areas of a naked body, while the third is made of semi-opaque white Perspex. A few years later, Watts developed a variation on these works with electronic components that were triggered by natural movements, such as Birthday Reminder (1971), in which the position of the sun triggers an electronic tone as a happy birthday greeting each year, and Cloud Music (1974), in which an electronic sound synthesizer responds musically to the passing of clouds in the sky.

Up to 1974, Watts’s works reveal the effect of his studies in pre-Colombian art; indeed, Benjamin Buchloh has noted that this education was excellent preparation for making art in relation to the object world of capitalism.4 The following passage from Watts’s student essay on Kwakiutl bird masks suggests how this might be so: ‘Kwakiutl society was an ultimate expression of formalized aggression and personal hostilities. [The Kwakiutls’] most valued possession was wealth, not only the wealth inherent in material resources and manufactured goods but, even more, the intangible wealth value attached to songs, dances, crests and ceremonial prerogatives.’5

If we substitute ‘American’ for ‘Kwakiutl’, the passage seems completely consistent with the kind of training Watts would have received from his professors Paul Wingert and Meyer Schapiro as he analyzed the object world of masks, totems and fetishes. The emphasis on component parts in Watts’s work – seemingly a reference to the breaking down of commodities into increasingly smaller parts (i.e. body moles) that can generate increasingly larger profit – certainly was also grounded in such student research, as another passage from the term paper shows: ‘In many masks, the cautious delineation and separation of each design unit, i.e. the eye, pupil, nostril and mouth, each with their smaller subdivisions, suggest a certain formality and sophistication, and indeed, an element of compulsiveness [...] It is as though each small unit of the mask were a unit of wealth and it were necessary to assemble them all to attain a final fortune: the complete mask.’6

In the early 1970s, however, the anthro-pological aspect of Watts’s work emerges much more emphatically, perhaps because the ideas of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Carlos Castaneda were part of the cultural zeitgeist at the time, and mixed in with the technological and cosmological in the work of authors such as Buckminster Fuller and Marshall McLuhan, the serial Whole Earth Catalog (1968–74) and the epic novel The Urantia Book (1955).7 These were materials that Watts absorbed and pondered during a period of attenuation from studio work in the early 1970s. At this time he was also developing the series ‘Phono Records’ (1969–86), which treats the then-everyday object of the record as a mysterious and revered object to be remade in various ancient (twine, brass, wood) or futuristic (Perspex, formica) materials and hung on the wall like a relic.

The key year in Watts’s new approach to his work was, however, 1977 – the same year as nasa’s Viking mission to Mars, an event Watts’s archive shows he followed as intently as he had the moon landing in 1969. That was also the year Stewart Brand’s book Space Colonies was published, and when Charles and Ray Eames made their film Powers of Ten. In 1977, Watts participated in this reframing of earth from the perspective of outer space, taking on a strategy common to sci-fi writers of the decade: to project archaeological evidence of past, non-Western societies onto other locations in the galaxy. He made ‘Space Archaeology’, a series of vitrines approximately the size and dimensions of a shoe box or, in some cases, a flatter box most like the Perspex cover of a turntable. A narrative recounting the discovery of these objects accompanied the project plans:

On June 1974, a remote controlled space scow landed in a field nearby at approx. 5:25am. [The] scow was used to search and collect flotsam from spacecraft as well as artefacts from other planets within a system. The exact purpose is unknown.

This event afforded me a chance to add to my own collection of artefacts from other worlds. Some objects are reminiscent of those from some past time and are considered by authorities to be ‘low craft’. Others are more advanced and are known as ‘high craft’. In most cases the exact civilization is unknown and only by inference can we speculate about these rather peculiar artefacts. In some cases the materials are known to us, but in most instances analysis has failed to detect the properties of the materials.

Bob Watts, 2121,

Alice-Ester Satellite8

In their eerie beauty, the objects inside these vitrines suggest artefacts that have aged in an alien environment, but at the same time, they come from television, or from the integration of space travel fantasy into the culture at large. As always, Watts is concerned with exchange value, and these objects are shiny, golden or silver in tone and finely made, a fusion of technology and Minimalism.

Of all these objects, the most peculiar are those in the ‘Cosmic Credit Card’ series (1983). These cards are irregularly shaped, striated, thin sheets of silver and brown rock imbedded with bits of metal rods cut as rings of various sizes. This artefact of our age, the plastic credit card, has been re-imagined as a beautiful and valuable childhood fetish that shines like money. It is for use, as the accompanying note specifies, ‘a) in the galaxy of your choice; or b) general purpose.’ Appearing in one of the ‘Space Archaeology’ vitrines, the cards were also made in a set of two and of three, in flat hinged wooden boxes like those containing parlour games.

Watts’s artistic inquiries into the home, in his last decade, generally occurred in the garden and the sky.9 He created a series of gardens, ‘like Stonehenge’, aligned with the heavens. Trace Moon Gardens (c.1977), the most developed idea in his garden project plans, involved creating reflective surfaces, whether ponds or mirrors, in linear configurations that would ‘capture’ the moon in its trajectory across the sky. Some plans included an electronic projection from the outdoors to the indoors, where home dwellers could watch the constellations ‘live’ on a movie screen.

The landscapes designed for the home in the 1960s become, in the 1980s, landscapes from another planet that is ours. Of these obscure works, perhaps the most poignant is Mountain That Withdrew From the Trees (1986). An illuminated vitrine, it portrays fir trees being abandoned by the mountain they had been growing on for decades or centuries. Left with only transparent plastic stands to support them, they recall the legions of fir trees sacrificed to Christmas each year. As such, they represent nature’s response to an array of human abuses. In calm retribution, the mountain has given up sustaining their lives.

One of Watts’s last works returned to his archaeological studies. Arrangeable Surface from the Plain of Nazca (1987) refers to the Nazca people, associated in the art historian’s mind with the work of Robert Morris or Robert Smithson, and in the popular imagination with Erich von Daniken’s theories that extra-terrestrials built the Nazca lines as a landing field for their spaceships. Before the appearance of any of this work, however, in 1951 Watts had written a term paper about Nazca pottery, which considers the Nazcas’ obsession with death and the various rituals and totems they developed to protect themselves against it. In Arrangeable Surface ..., Watts combines the movable landscapes of his interior design phase with the parlour games of his later phase, only this piece is a game played by the Nazca gods in which the fate of Watts, who then had lung cancer, was to be played out. At the same time, it is an offering composed of artefacts that are lovely, strange and classifiable – if not entirely interpretable.

This essay is a project of the Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers’ Grant Program. I am indebted to Larry Miller and Sara Seagull, executors of the Watts Estate, for numerous insights and clarifications about the artist and thank them for granting permission to reproduce photographs of Watts’s work and citations from the archive.

1 Robert Watts Papers, 1883–1989, bulk 1940–88, Box 12, folder 19, Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, Accession no. 2006. M. 27

2 Eds. David Crowley and Jane Pavitt, Cold War Modern: Design 1945–1970, V&A Publishing, London, 2008

3 New York Times Sunday Magazine, 26 September 1966, pp. 72–3

4 Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, ‘Cryptic Watts,’ Robert Watts, Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, 1990, p. 7

5 Robert Watts, ‘Kwakiutl Bird Masks’, 1950, pp.1–2, Watts Papers, Box 5, Folder 2

6 Ibid. pp.15–6

7 Interview with Larry Miller and Sara Seagull, 16 July 2009, New York City

8 Watts Papers, Box 12, Folder 28

9 Sid Sachs, Watts Natural, Lafayette College Art Gallery, Easton, Pennsylvania, 1991, p.6

Robert Watts was born in Burlington, Iowa, USA, in 1923 and died in 1988 in Martins Creek, Pennsylvania, USA. His work has recently been included in ‘Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life’ at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery (2011), and University of Michigan Museum of Art (2012), USA; and ‘Thing/Thought: Fluxus Editions, 1962–1978’ at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA (2011). In 2012, his work has been featured in ‘John Cage: A Centennial Exhibition (With Friends)’ at the Carl Solway Gallery, Cincinnati, USA, and will be included in ‘Lost in LA’ at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, USA, in 2013.