Three Summer Shows

Pilar Corrias, Maria Stenfors & Max Wigram Gallery, London, UK

Pilar Corrias, Maria Stenfors & Max Wigram Gallery, London, UK

Group shows are an effectively elastic form – they can propose, critique or arrange; they can act as a portrait of the tastes or trends of a moment, whilst still, in some small part, acting as a form of conceptual self-portrait of their curator. The artist-assembled show more openly defers to this sense of autobiography: the artist’s research, their way of thinking, working and looking at the world. A notable number of London’s commercial galleries gave themselves over to artists’ choices this summer – from Dan Coopey’s ‘A Merman I Should Turn To Be’ at Laura Bartlett, to ‘World Music’ curated by Steve Bishop and Richard Sides at Carlos/Ishikawa, and Will Benedict’s ‘Nuclear War: What’s in it for you?’ at Vilma Gold. Perhaps symptomatic, given the personalities hovering over the works, many of this summer’s shows offered parallel, sceptical musings on presence.

At Maria Stenfors, we were anticipated before we even arrived. ‘Welcome!’, was heard cheerily reverberating around the gallery. The host was an eager man, his head in close-up on a monitor, his face slightly scuffed as if he’d been sleeping rough for a day or two. His grinning salutation quickly gives way as his face slumps. ‘I’m sorry’, he solemnly whispers. Suddenly he’s bright eyed again, giving another fervent ‘Welcome!’ repeating the two expressions ad infinitum. Alan Currall’s videos – the aforementioned Welcome and Apologies (2012) at one end and a similarly looped Congratulations and Goodbye (2012) at the other – bookended the four-man show, ‘Ideas in Things’, curated by artist Dean Hughes. The characters in the videos stare out at us, as if we were mirrors in which particular modes of human interaction were being rehearsed. This sense of slightly glassy-eyed detachment from convention permeated the show – in Juan Cruz’s jigsawed canvases made up of reconfigured navy blue trouser and jacket bits (Suit 1 and Suit 2, both 2013), and David Blackaller’s geometric arrangements of painted wood, which hung sparsely about the place like mini railway semaphores. In the video Picture Object Performance Series (2008–09), Siân Robinson Davies gives a silent desktop demonstration of the slippages between types of representation. Making a sequence of collages from magazine clippings and props like a pear and a light bulb, non sequiturs become landscapes and playful visual puns. At one point, Davies holds up an image of a helicopter in one hand and a small toy one in the other. She rotates each so that we see them from above; both the toy’s propeller and the photograph appear, of course, as only a flat line. With ‘Ideas in Things’, Hughes seems to gently prod a double-bind: no matter how hard we try to depict something directly, it always slips away, morphs into something else. The show is pleasurably pessimistic; the ideas in these things remain latent, and if their communication is at all possible, it can only be as an improvised translation, making what we can of the outburst of a stranger encountered on the street.

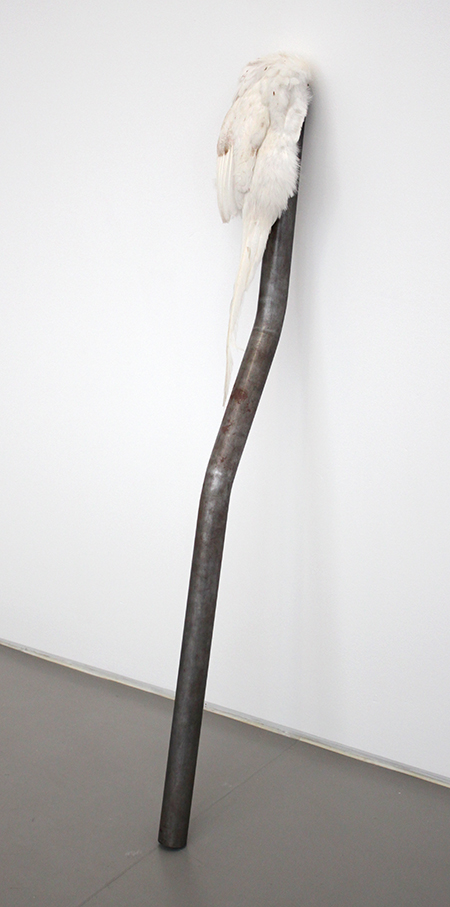

Things were more literally concrete at ‘Ice Fishing’, a four-artist group show at Max Wigram put together by new director Darren Flook. The gallery felt like a neglected storage room in a hardware store, with a stack of bricks and bits of wood leaning against the wall next to Charles Harlan’s Concrete (2014), seven stacked lumps of the material that have been left to harden in the sacks in which the constituent powder comes. ‘Ice Fishing’ prioritized arrangement as an artistic activity – from Virginia Overton’s Untitled (silver) (2013), a set of mirrored, semi-circular strips positioned at regular intervals along one wall, to the dark humour of Michael E. Smith’s Sleep (2013) in which a flaccid chicken hangs with its head stuck in an upright car exhaust pipe. The oblong canvas of McArthur Binion’s DNA Study: Circle (2014) is a dense black shape until, from up close, we can just about make the words: ‘How many children were born dead?’ The American artist’s seemingly minimal images are thick layers of smudged crayon over documents such as his Mississippi birth certificate or, in Stelluca: V (2011), the logo of a company bearing the outdated racist stereotype of a black ‘mammy’ character. The bleak landscape suggested by the show’s title implies a world in which things are as they appear but, as Binion’s work attests, all objects are marked by their accruing histories, which they carry with them, however reluctantly.

‘Phantom Limbs’ at Pilar Corrias, by contrast, attempted to entirely bypass matter itself. Including work by eight mostly young artists, the show felt like the gallery’s attempt to weigh in on the ‘digital issues’ facing us at the moment, with ‘things’ replaced by their 3D-rendered or HD counterparts. Ian Cheng’s CEO & Ceong (study 1) (2014) is an endlessly running digital animation, depicting a snow-covered tundra landscape filled with llama-like animals and almost human stick figures. They wander, stumble and morph in an angular, unfinished digital purgatory. For an exhibition about missing appendages, ‘Phantom Limbs’ was fairly heavy-handed in its treatment of ‘the digital’ – as exemplified by Antoine Catala’s :) (2014), a 3D-printed emoticon mounted on motorized bars that limped around the gallery. The exhibition was salvaged by one of the oldest works on show, Ken Okiishi’s live action film, E.lliotT:. Children of the New Age (2004), in which affectless teens enact a suburban life filled with wrong-looking ‘imperial un-meatloaf’, cross-dressing, psychological testing and zombification. Everything here feels like a swipe or quote from somewhere else, whether E.T. or urban legends. Okiishi’s video suggests that the transformations (and attendant sense of leaving something – perhaps ourselves – behind) that the digitial era has made us so anxious about have been happening through books, films and oral history for some time already. Rachel Rose’s short video Palisades in Palisades (2014) nimbly plays on these issues, deliberately presenting us with stand-ins and feints. In one scene, we see a digital 3D animation of a deer being shot through the heart and follow the perspective of the bullet, as if into the animal’s flesh. Once inside the heart, the camera pulls out to reveal it to be an orange plastic bag. Though ‘Phantom Limbs’ tries to formulate new thoughts that might come from a world of ‘post-things’, it remains caught in a tired, almost tit-for-tat exchange between the physical and the digital. But, as Rose suggests, it’s the wild, unpredictable and exhilarating associations and transformations between things in any form that will shape that world.