In Two Places

Amy Sherlock chairs a discussion between Caroline Achaintre, Aaron Angell, Alison Britton and Richard Slee about their work in clay

Amy Sherlock chairs a discussion between Caroline Achaintre, Aaron Angell, Alison Britton and Richard Slee about their work in clay

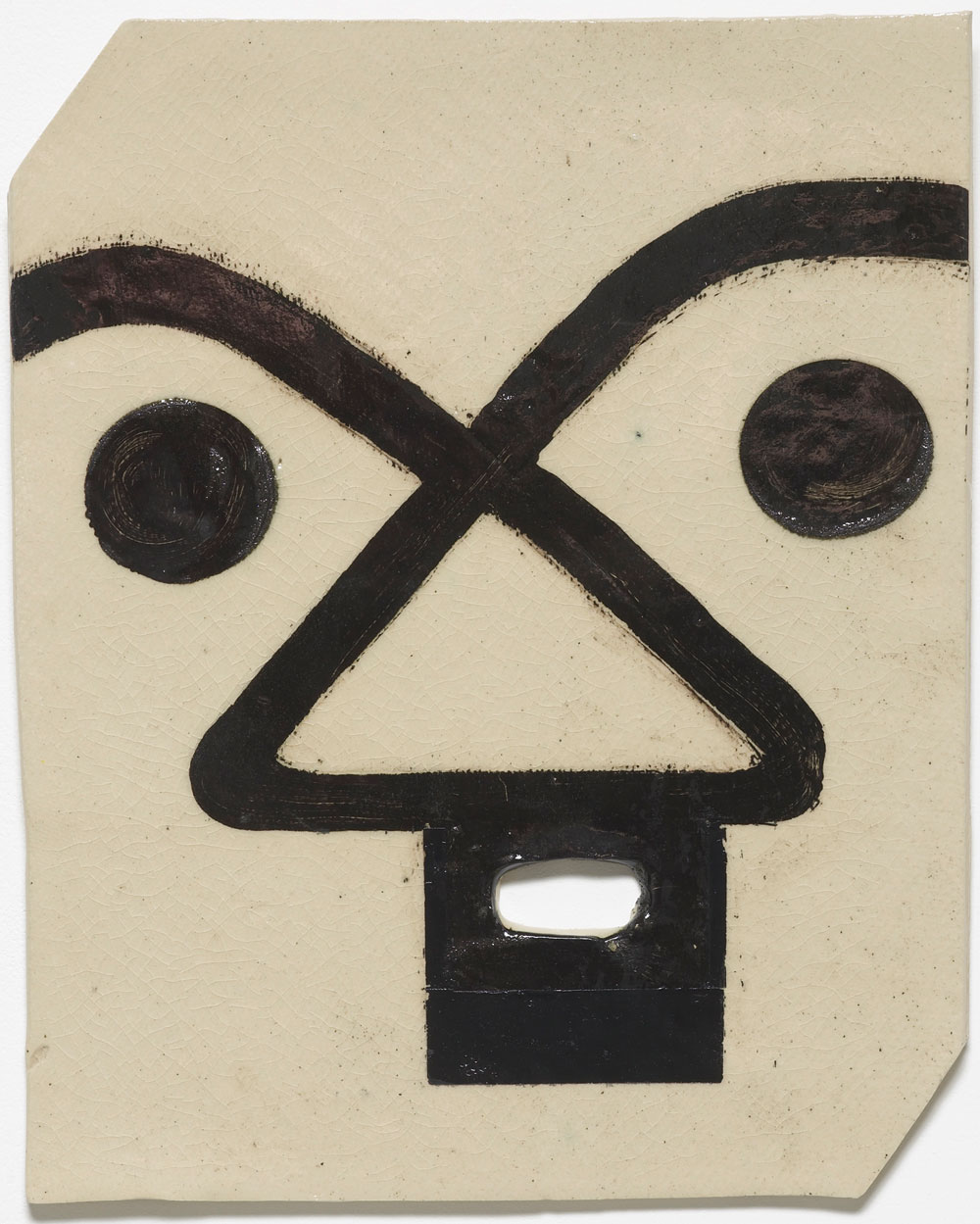

Caroline Achaintre is based in London, UK. Recent solo shows include Arcade, London (2016), Tate Britain, London (2016), and Castello di Rivoli, Turin, Italy (2014–15). Her ceramic and textile works are currently included in the touring British Art Show 8, UK (until 2017), and her solo show at c-o-m-p-o-s-i-t-e, Brussels, Belgium, runs until 28 May. She has work in the group exhibition ‘A Conversation about Ceramics’ at Monica de Cardenas, Milan, Italy, which closes in July, and a solo presentation at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK, which opens that month.

Aaron Angell is based in London, UK. He works primarily with ceramics, producing sculptural tableaux referencing hobbyist cultures, naturalistic forms and the underground hand-built ceramics of Britain from the 1970s and ’80s. This year, he had solo shows at Markus Lüttgen, Cologne, Germany, and at Glasgow Botanic Gardens and Kelvingrove Museum, UK, as part of Glasgow International 2016. His work is currently included in the touring British Art Show 8. He is co-curator of ‘That Continuous Thing’, a major survey of artists and the ceramic studio, which will open at Tate St Ives, UK, in spring 2017. Angell is the founder and director of Troy Town Art Pottery, a ceramic workshop for artists founded in response to dwindling access to ceramics studios in London.

Alison Britton has run a studio in London, UK, and made pots for the past 40 years. She also curates exhibitions and teaches in art schools; since 1984, at the Royal College of Art, London, where she is a senior tutor in ceramics and glass. Her work has been widely shown across the world and Seeing Things, a collection of her writings, was published by Occasional Papers in 2013. Her retrospective exhibition, ‘Content and Form’, runs at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK, until September.

Richard Slee is based in London, UK. He studied industrial design and then ceramics at Central School of Art and Design, London, graduating in 1970. He gained an MA from the Royal College of Art, London, in 1988. He has taught in art schools both in the UK and abroad, and was course director of ceramics at Camberwell College of Arts, London, from 1995–98. His work is currently on show in the survey ‘CERAMIX from RODIN to SCHÜTTE’, which runs at Cité de la céramique, Sèvres, France, until July, and his solo show, ‘Work and Play’, toured various venues in the UK in 2014–16. His work will be included in upcoming group exhibitions at Dovecot Gallery, Edinburgh, UK (September 2016), and Tate St Ives, UK (spring 2017).

Amy Sherlock Clay is experiencing something of a boom in the art world. For the past four or five years, I have seen an increasing number of artists – particularly young artists – working in the medium, often as one material strand among many in a multi-disciplinary practice. Concurrently, there has been a renewed interest in, and market for, ceramic work by older and historic figures – from Hans Coper and Lucy Rie to ‘California clay’ artists such as Michael and Magdalena Frimkess, John Mason and Peter Voulkos to the Japanese mingei potters Kawai Kanjirō and Hamada Shōji.

I am also an amateur potter and have seen ceramics courses becoming increasingly popular, with studio and kiln space now at a premium in London. You all are artists who work with clay, although with varying degrees of exclusivity and to different ends: why do you think the medium is experiencing this new-found popularity?

Caroline Achaintre I think, in general, people are more interested in process-based work; it’s not so much about ceramics on a conceptual level, but as a method. Clay is one of the easiest mediums to use – at least to begin with – although it can be used in a very elaborate way, too.

AS Alison and Richard: you have both worked with ceramics for your entire careers.

Alison Britton Since I was nine or ten.

AS Over your many years as a tutor at the Royal College of Art, have you seen changes?

AB I teach in the ceramics department, so it’s pretty consistently been people who know they want to work with clay coming through our doors. Ceramics has never gone away, it’s just that general culture rediscovers it from time to time.

Richard Slee Alison is teaching at a postgraduate level where I’m sure there is a consistent demand for specialist ceramic education. However, throughout my career, I’ve seen the collapse of ceramic education in this country and in Europe (though, interestingly, not in America). Basically, from a high point somewhere in the early 1980s, there’s been a gradual decline. There are many reasons for this, I think. A lack of passion, certainly, but also because the facilities in schools closed down, one presumes because of expense, as well as health and safety regulations.

Aaron Angell My secondary school used to offer ceramics as an O-Level, before I was there. The legacy was that we had all these big electric kilns from the 1980s that were still in good nick. I didn’t do any ceramics while I was at school, I should say. But I went back later, when my younger brother was still studying, and asked if I could make work there. It was great: I ate school dinners again for a few months; I loved it!

RS I was head of department at Camberwell College of Art in the 1990s, and you sensed that interest was falling off. At that point, there were 30 undergraduate courses that had ceramics in their title and now I think there are about two.

AS Is that something to be lamented?

RS No, not for me. A lot of my fellow tutors would go on about the loss of skills, the loss of knowledge, but I’m not sure. That knowledge was actually built up very rapidly postwar, from the 1950s. Before that, I think if you went into a college ceramics department, it would be one kind of clay, one man and one dog.

Alison and I went to what was then Central School of Art and Design in the early 1960s. It was a period of enormous expansion in technology and of real investment in art education in the UK – in fact, in higher education more broadly. You could sense the tutors were learning as much as you were at that time; it was an incredibly creative moment, a real community of learning. Sadly – now, I sound like I’m contradicting myself – something went wrong. Personally, I think that had a lot to do with isolation and fashion.

AS Do you mean ceramics becoming isolated from the broader conversations that were going on in art departments from the late 1970s?

RS Yes, probably.

AS Caroline or Aaron: neither of you studied ceramics formally. What were your routes to the medium?

CA About five and a half years ago, I was making work out of paper. Paper has a short life-span in terms of sculpture, so I was looking for a way to solve that and clay seemed like one solution. It might well have been something to do with the zeitgeist but, you know, when you are at the beginning of something, you don’t really think about it.

Virtually all of my work has been domestic in certain ways; it's meant to go inside a room. I call it the drama of the Great Indoors. Richard Slee

AB I’m curious about the Slade [where Angell studied as an undergraduate, between 2007–11] because some of the tutors there have used ceramics a lot – Edward Allington and Bruce McLean, for example. It’s odd that nobody was bringing it in. Surely there would have been tons of clay at the Slade, just for modelling?

AA Exactly – there was a kiln, but it had been half-decommissioned to a lower temperature to burn out moulds.

I’ve been seeing clay used more by recent students: I went back and gave some tutorials a year or two ago and everyone in the sculpture department had some sort of ceramic on their desk. It was intriguing – most people have been using it as a means to an end, a sculptural material like any other, which was the basic gist behind me opening Troy Town Art Pottery: to invite other artists to come and use clay to make something that wasn’t a pot.

RS Thinking about it, sometimes if you take something away for a period, it becomes attractive again. Maybe the disappearance of formalized ceramics was, in some ways, a good thing.

AA There’s always a certain naivety from people at first – including myself, when I started. You can flick through issues of Ceramic Review and see all these lumpy sculptures and think: God, why isn’t everyone doing this? It must be the easiest thing in the world.

I have a slight problem with this idea of clay ‘coming back’. We can talk about fashion, but there are threads all the way through. To answer the question ‘why now?’ – I think there is a certainly a reaction against the kind of fabrication fetish that we have been seeing in a lot of work over recent years.

AS You mean the outsourcing of production?

AA Yes: outsourcing and also losing this one-to-one scale of body to material, which is so inherent to clay. Philosophically, you can treat ceramics as this thing that turned against modernism …

AS Or that modernism turned against, because it was certainly there at the start, with people like William Staite Murray.

AA In a technical sense, it was involved deeply with industrialization and mining: different ceramic surfaces require discrete materials and there’s lots of geopolitical stuff surrounding these at a micro level. At the same time, low-fired ceramics can be made in a beach fire and last 5,000 years – it’s as primitive a technology as cooking.

CA But, ceramics was also part of modernism.

AB There is quite a strong lobby of thinking that puts Bernard Leach into the modernist framework. You can argue that he was looking outwards to Eastern models to reinvigorate what was happening in Europe, in a comparable way to Pablo Picasso looking at African artefacts.

AS Alison, you once wrote in an essay that ‘clay, as a material, is prone to metaphor’, which is perhaps why it so easily assumes these different meanings at different points.

I have been thinking about that in relation to Caroline’s work, particularly the ceramic pieces in the recent show at Arcade gallery, which looked almost like snake skins. It ties to what you were saying earlier, Caroline, about using clay to replicate the forms that you were making in paper. Clay is very good at disguising itself as something else, which might be one of the reasons for its appeal.

AB As a substance, it’s formless: it’s a sticky mass, which has, throughout history, been used to imitate jade or bronze or other materials that were more precious. There are lots of historic cases where clay has been used to echo the metal forms – ewers in Chinese art or the fluted silver dishes copied in Moorish Spanish ceramics. Often, the metal pieces have been recycled but the ceramics survive.

AS How does what is going on in ceramics relate to discussions around deskilling, which many people see as one of the lasting legacies of conceptualism on arts education? I was talking to Betty Woodman [for frieze issue 177] and she said something quite interesting: in order to be an artist working with ceramics today, you have to make a disclaimer about not knowing what you are doing, technically speaking.

AB When I first graduated, a lot of conversations I found myself having were about what temperature you fired something at or what you put in glazes. No one wanted talk about what the thing was or why I’d made it. Initially, I was keen to push away anything to do with technique and skill. I thought: ‘We have it but we’re not going to go on about it.’

But now, having gone through close to 40 years of seeing everyone gradually getting less and less skilled generally, I have swivelled around. I do think that skill-lessness is a really worrying phenomenon, as we move forward.

AA The point about talking shop is really interesting. Take Troy Town: normally, I would talk conceptually, for want of a better word, about things with other artists but, in the pottery, it instantly becomes technical.

You wouldn’t walk into a room with a patinated bronze in it and start discussing the process of patination or the history of wax casting. That’s all really interesting, but it doesn’t bear on the object as much as with ceramics, somehow.

AB I think it might bear as much, it’s just the habit is not to talk about it.

AA Perhaps. But I also think it’s because ceramics, in my opinion, is the most complicated sculptural method, once you get down to it.

RS As an educator, I often wished that there was some kind of serum or something I could inject my students with, which would contain all of that technical knowledge. It’s a long apprenticeship, ceramics; you have to go through the pain barrier.

AS Alison, you came out of the ceramics department at Central with this enormous technical skill …

AB It wasn’t enormous.

AS But you had a grounding and a certain level of proficiency. Then, you went to the Royal College to do an MA.

AB My first sense, when I started, was that I had all these skills and no idea what to do with them. For me, it was the other way around: it took a long time to find what it was worth making with my hands.

AA At this moment, ceramics feels like a life sentence for me; I look at it that way.

AS In terms of being committed to developing technically or because you feel you’re being pigeonholed – by people like me?

AA No, I don’t care about that. I mean in terms of my own intentions. You can do ceramics for 50 years and not know what’s going to come out the other end.

AB The uncertainty of it is a huge part of the attraction for me.

AA The kiln is something you submit to.

RS I find that an incredibly romantic notion.

You wouldn't walk into a room with a patinated bronze in it and start discussing the history of wax casting. That's interesting, but it doesn't bear on the object as much as with ceramics, somehow. Aaron Angell

AB You’re much more precise.

RS I want to know what happens; I want to be in control. The accident isn’t always happy.

Speaking of craft, yesterday I saw a documentary about François Truffaut’s interviews with Alfred Hitchcock in the early 1960s [Kent Jones, Hitchcock/Truffaut, 2015]. They are speaking and Truffaut keeps using the word ‘craft’. There’s no guilt about it – they know it’s necessary: Hitchcock had to have great craft to make great films.

CA Does craft mean skill? I never understand because, for me, in that respect, painting is as ‘crafty’ as anything.

RS It means knowledge of your material as well, and judgement. You can have somebody who is an incredibly precise craftsperson and will make the most mundane work.

AB ‘Crafted to death,’ we used to say.

AS I think there is often a real fear of, or scepticism towards, virtuosity among contemporary artists. Somehow, as Aaron was saying, if you are incredibly technically proficient at something, that becomes the subject of whatever you make.

AB It gets to be mannerist.

CA It can be a distraction; I believe that. I didn’t learn ceramics but I trained as a blacksmith before becoming an artist, so I know that craft can also be an obstacle to what you’re trying to do. I think there’s a morality to craft that can definitely be in the way of the artistic ideal.

AB But only if you let it.

AS Troy Town is, emphatically, an ‘art pottery’. It’s resolutely anti-vessel.

AA Well, that was my line at the start. Generally, the people I work with are not ceramicists so, as a matter of course, they’re making sculpture. The vessel doesn’t come up as often – actually, hardly at all – in other media.

AB Terrible word, too.

AA Vessel?

AS What would you prefer?

AB Pot is a better word. Pot is good.

AS Alison, you’ve stuck with the pot form in various permutations for your entire career and you’re still experimenting with it.

AB Yes, I don’t seem to run out of interest. There’s enough to work with, with that as a given.

AA The idea of the pot as a given?

AB Yes, I do think of the pot as a given; it’s something I have no need to fight.

AS What about you, Richard? You made a decisive break with the vessel form many years ago.

RS I made a deliberate decision not to reference the pot or pottery. I felt that I’d run dry; my commentary on pottery was ironic and the joke had gone. But, then, I can’t deny my roots, which are pottery roots. Virtually all of my work has been domestic in certain ways; it’s meant to go inside a room. I call it the drama of the Great Indoors.

AB It’s still controversial for some artists, isn’t it, the idea of the domestic? It’s slightly boring. I was at a symposium at Yale not long ago, on a panel about an exhibition called ‘The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art’. Some of my American co-panellists were surprised that I was talking about the domestic space, as if it were a strange subject.

CA You mean in a psychological way?

AB Just that I wasn’t only thinking about making a big splash in large institutions.

RS There is a tale about Voulkos doing a demonstration where he was really drunk. His advice was: ‘If you can’t make it good, make it big.’

AS Voulkos’s work is the opposite of domestic. That is perhaps why it was accepted very early on as a legitimate art form: because it was so far removed from tableware. Where do you see your works living when you make them, Alison?

AB In rooms. It’s about scale. People have often asked me why I don’t make the pieces bigger. I have no desire to make them bigger.

Ceramics has never gone away, it's just that general culture rediscovers it from time to time. Alison Britton

AA It’s also difficult.

AB It’s not impossible, but I want to be able to lift them up and move them around.

AS You want to retain that connection with the body?

AB Yes. I’m always making bodies. And there are ways in which you can easily pick my pots up – it’s about physical interaction.

AS Caroline, is there a conversation in your mind between your textile pieces and the ceramics?

CA When I end up showing them together, certainly. Sometimes, the same process or form will find its way into both – a way of folding, for example. To that extent, they influence each other. I like showing them together because there are nice correspondences: the wool is quite an eerie material, shaggy and attractive yet repulsive at the same time; whereas clay, at least as I use it, has a seductiveness.

AB It can be repulsive, too.

CA Absolutely.

AS How did you start working with wool?

CA Again, I didn’t learn formally. For my MA I was making small, intense watercolours that dealt with uncanniness. I wanted to somehow enlarge them and, thinking about how the uncanny and the familiar are related, it struck me that I should use a domestic material. That doesn’t interest me so much anymore – I don’t see the work necessarily as a comment on domesticity.

It’s quite a potent process, tufting: you use an air tool, which shoots wool through the canvas. It’s not like weaving; it’s fairly swift and physical.

AS Do you feel, like Aaron, that ceramics is a life sentence?

CA I’ve been tufting for over ten years and I’ve never thought: ‘That’s it, I’m going to stay with wool now.’ A friend has just given me an old kiln because he’s moving to the US and I’m building a shed in my garden to put it in, which is a commitment. It’s a journey and, at the moment, it’s going well, but I can’t say if it’s for life.

AS Aaron, do you envisage Troy Town becoming self-sustaining? Or do you consider it to be a core part of your practice?

AA I’m trying to get to a point where I am spending less time there. Troy Town is moving and expanding in May, so I think there will be some changes. It feels as though the initial stage of the experiment is over. When we first started, I was working with five artists a month, which was insane. Now, I work with two artists a month, if that, and it will become less regular, which will maybe allow a bit more time for research.

AS Are you reskilling through the back door, as it were, in the absence of ceramics departments in colleges and schools?

AA I don’t have the skills, or the people skills, to teach. There are three things I tell people on the first day: don’t go more than an inch thick anywhere; don’t make any contained spaces because the piece will explode; and put your work under the fan for a while, or leave it until the next day, to harden up. That, and how you slip two pieces of clay together to make a join. It’s half a day’s worth of teaching.

CA When I was there, it impressed me that you were just left to yourself to begin with but, if you wanted to know particular things, you could ask. I think that’s much better: to work it out as you go.

AS There’s a famous quote from Hans Coper, which I’m sure Alison probably knows off by heart, because it’s often mentioned …

AB The only thing he ever wrote!

AS … from the exhibition catalogue of his Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition in 1969. He says: ‘Practising a craft with ambiguous reference to purpose and function, one has occasion to face absurdity. More than anything, somewhat like a demented piano-tuner, one is trying to approximate a phantom pitch.’ It struck me as an apt way of describing …

AA … trying to make something that’s somehow between two worlds.

AB I think he’s talking about what happens if you put function aside; what, then, are you hanging onto?

AA I think if you’re making something out of clay that isn’t visually fitting, which doesn’t formally reference functional things, you don’t need to answer that question. My favourite ceramics in the world are anatomical Etruscan votives that were made between 200 BCE and 200 CE. These were mass-produced sculptural ceramics and, of course, they did have a functional value in their society, but they’re not vessels, they’re not pots, and somehow you can’t fit them into that conversation.

AB I think Coper had a notion of all different kinds of function.

AS Certainly, but I do think ceramics, at this moment in time, is in two places: there is a revival in artists using it sculpturally and, at the same time, there are communal craft pottery studios opening – places like Turned Earth in Hackney or the Ceramics Studio Co-op in New Cross – where people are making and selling functional ceramics. I think that’s part of the same mentality as craft beer and farmers’ markets: it’s linked to a certain ethics and politics of production and consumption.

RS The Granby Workshop [a social enterprise set up by Assemble as part of their Turner Prize-winning Granby Four Streets project in Liverpool] is an interesting example: lovely people with lovely intentions, I’m sure, but their actual products are dreadful.

AA I thought you would have liked them; it’s all brooms with carrots for handles and things like that.

RS They’re not well-designed and, actually, in craft terms, they’re dreadful because they don’t work: the materials are wrong.

AB I’d like to say one more thing: craft occupies an unstable position in the spectrum of art design and I don’t think it has ever, since it was the normal way of producing everything, had a fixed place. It can be an absolute taboo at some points and, currently, it’s very appealing, but it’s always being redefined and always on the move. If you tried to put an edge around it, a defined border between art, craft and design, then you’d be stuck, I think. The discipline would die.