What We Can Learn from Okwui Enwezor’s Post-Colonial Ethics

In style as well as substance, the late curator embodied a politics of inclusivity

In style as well as substance, the late curator embodied a politics of inclusivity

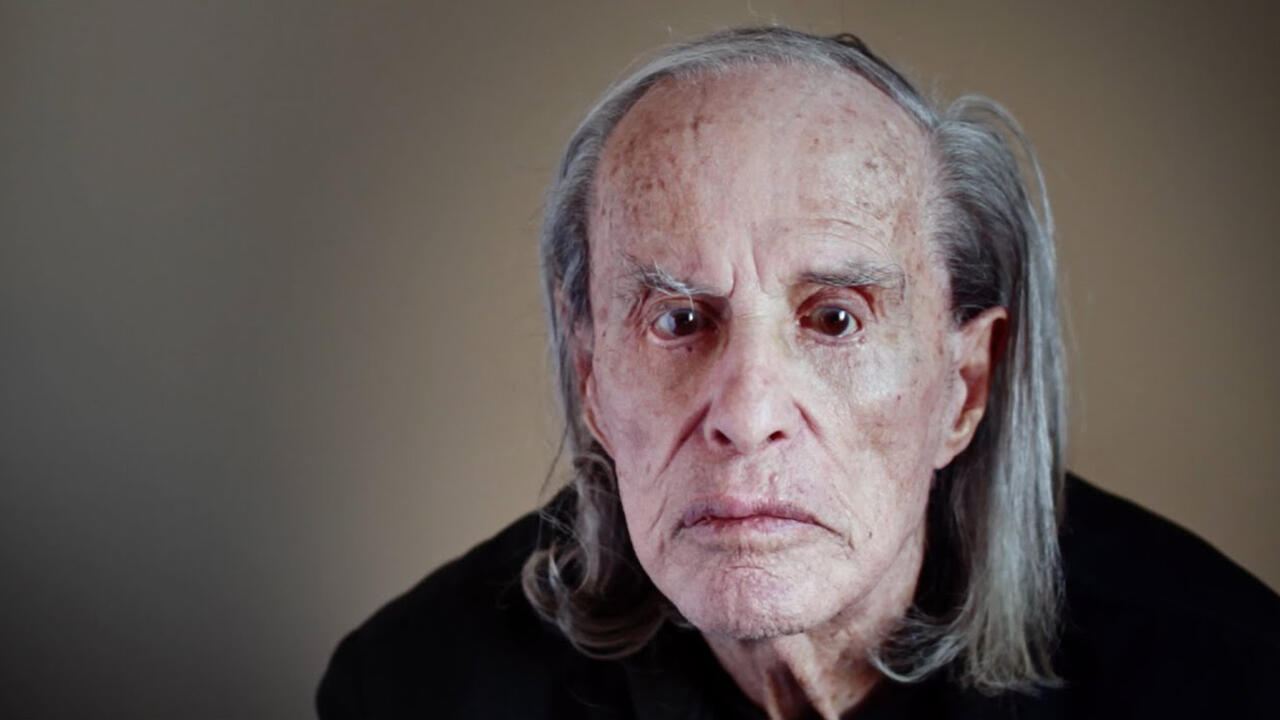

Lesser known among Okwui Enwezor’s many superlative skills and talents was his ability to gauge someone’s clothing size by eye. A handful of his fortunate friends and colleagues received elegant, timeless and unsolicited articles of clothing from him that fit perfectly. Already known as a dapper man and true aesthete, Okwui’s secret skill required the ability to see beyond the wrappings of coats and clothes, to the underlying structure and form of a body.

As it was with clothes, so it was with art. Many museological and art-historical narratives have been thrown into crisis over the past several decades, but Okwui’s post-colonial critique discounted the superficial need for a few new ones. What we need, in his estimation, is a restructuring of our conceptions of history and culture. Where some championed taste, he championed concepts; where others championed inclusivity, he championed alternative criteria. He will forever be appreciated for the way he and others midwived African art into the canon of contemporary art history, long dominated by European and American practices. When it hasn’t been completely disregarded, Africa has been exoticized and tokenized by Western institutions blind to alternate perspectives of time, history, aesthetics and belonging. In Okwui’s vision of the post-colonial, we must move beyond mere inclusion, expanding the matrix of culture and identity beyond any single line of thought.

Generous and gracious to the end, Okwui recently greeted dozens of people in hospital, despite the pain and fatigue he was experiencing. Our final conversation was about the social aspects of post-colonialism and its manifestation around the world. His conception of the post-colonial, he told me, was always broader than the breakdown of cultural and political imperialism. He always imagined it to encompass the many concurrent social movements of the mid- to late 20th century that chafed at naturalized hierarchies – the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, LGBTQI+ advocacy, environmentalism – and allowed for more social, political and psychic liberties than had been possible for prior generations.

For Okwui, post-colonialism was an ethical position. He envisioned a world which condemns violence and the policing of others’ voices and bodies. This is as much about the way we produce art histories as it is about the way we function in our societies. I hope we all learn to live up to his standards.

This article appeared in frieze issue 203 with the headline ‘Okwui Enwezor 1963-2019’