A Cyborg Couture

How cyborg identities have empowered women to challenge societal norms

How cyborg identities have empowered women to challenge societal norms

Over the past year, machine learning and AI technology have seeped fully into fashion consciousness. From emerging brands to luxury fashion houses alike, the fervour for cyborgs and human-machine hybrids has manifested on the runways to such an extent that ‘cyborg couture’ has become the new norm. Models gliding down the runway on a conveyor belt (Dior), transformed into otherworldly creatures with facial prosthetics (Rick Owens), rendered triple-breasted (GCDS), carrying replicas of their own heads (Gucci) or clad in ‘futurewear’ (Marine Serre) are but a few recent examples of this widespread trend.

The brilliant British designer Alexander McQueen was way ahead of the curve, recognizing the cyborg’s liberating potential to unleash desires that would not otherwise be physically feasible, or deemed morally acceptable, long before the rest of the industry caught on. In the iconic finale of McQueen’s Spring/Summer 1999 show, two industrial robotic arms sprayed yellow and black paint on model Shalom Harlow’s white dress as she spun helplessly on a revolving floor. Once the dress was daubed with colour, Harlow walked down the runway dizzily, triumphantly presenting her newly machine-made look.

The cyborg moment in fashion seems an apt, and inevitable, arrival in the current political climate. In the face of Trumpian populism, Brexit, right-wing nationalist rhetoric, climate change, the #MeToo movement and Facebook privacy breaches, our future feels more uncertain than ever. In this context, the post-gender, post-human cyborg presents itself as the perfect means of combatting our dystopian present. Instrumental in popularizing this notion within mainstream culture was Donna Haraway’s seminal 1985 essay ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’, which describes a society where the boundaries between humans, animals and technology are obscured. Cyborgs, monsters and hybrids, unencumbered by gender or societal restrictions, are proposed as a viable apparatus for transcending reality.

Yet, the cyborg concept can be traced back far earlier. Prompted by their experiences during World War I, Dada artists likewise advanced the notion of a ‘new human’ for a utopian society, one networked within newly formed mass communications. It was perhaps Raoul Hausmann’s speech at the group’s first official evening of lectures and readings at Berlin Sezessian on 12 April 1918, during which he referred to human as a hybrid identity of organic and technological, that foregrounded the group’s foray into cyborg representation. Hannah Höch, the group’s sole female member, created photomontages that juxtaposed a fashionable, independent, working ‘new woman’ that emerged during this era with domestic and industrial appliances. For Höch, the photomontage lent itself to social and political commentary, allowing the artist to visualise the public’s curiosity and fear about women’s newly elevated, post-suffrage social status.

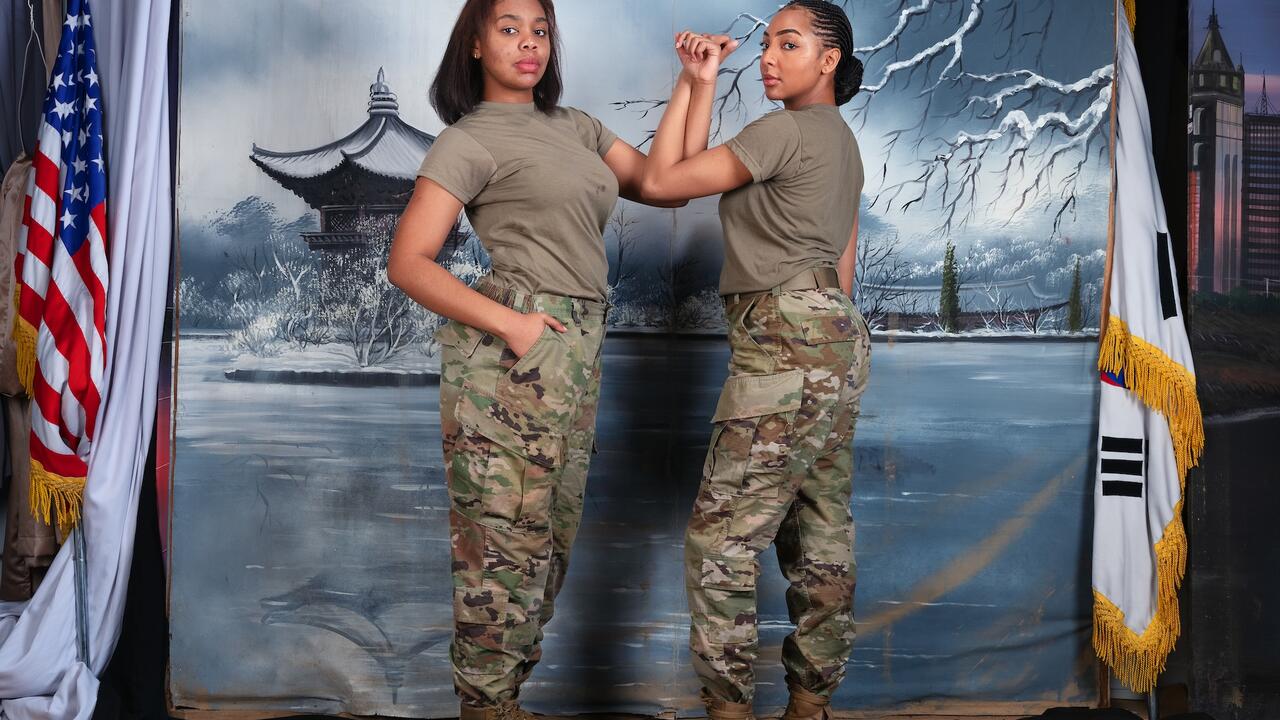

Likewise embracing the cyborg identity as a mechanism for protest and social criticism, the work of artist Lee Bul (b. 1964) is rooted in her experience of growing up in South Korea during the 1960s and ’70s. While this period was marked by rapid industrialization, economic growth and modernization, it was also an era of oppressive military dictatorship under president Park Chung-hee, in which the patriarchal ideologies stemming from the country’s Confucian heritage were – and still are – very much prevalent.

Lee’s iconic series ‘Cyborg’(1997–2011) and ‘Monster’(1998–2011) – which draw closely on Haraway’s explicit, post-humanist definition of cyborg as the ‘other’– evolved from her earlier performance works. In Abortion (1989), for instance, the artist’s naked bondaged body was hung upside down from the ceiling while she recounted, and re-created, the pain of her own abortion – a procedure that remains illegal in South Korea until last month. For Sorry for suffering – You think I’m a puppy on a picnic? (1990), Lee roamed the streets of Seoul and Tokyo for 12 days in a multi-limbed monster suit, much to the alarm and consternation of onlookers. With the distinction between its external limbs and internal organs blurred, this uncategorizable ‘soft sculpture’ body suit appeared human yet monstrous, familiar yet uncanny, affording the artist a liberty not ordinarily bestowed upon her female Asian body. Lee’s works succeed in openly challenging the social and cultural conditions of her home country by embracing the post-gender, monstrous, cybernated body. It was also the only viable entity onto which to project and realize her utopian longings and fantasies.

Japanese artist Mariko Mori, a peer of Lee’s, has also explored cyborg identity; in her early works, she adopted it as a means of addressing outdated notions of femininity in her home country while exposing the complications arising from the convergence of traditional Japanese culture and religion with modern technology and global consumerism. In Tea Ceremony (1994), for instance, Mori dons both a conventional work uniform and a silver cap with pointed ears to serve traditional Japanese tea to passing businessmen on the city streets. Similarly, Play with Me (1994) shows Mori standing outside a gaming store in a hybrid anime/robot costume. By aligning herself to the shop’s inanimate plastic figurines and video-game characters, the artist questions and subverts the submissive role a woman is traditionally expected to adopt in Japan; the separation between cyborg and woman becomes indistinct– they are one and the same.

Artists like Höch, Lee and Mori perhaps laid the groundwork for the recent upsurge in cyborg fashion by being one of the early pioneers in galvanizing the cyborg’s potentials. The cyborg identity has provided a platform from which to openly criticize the reality of being a woman in a patriarchal society and to actively champion women’s new status in the modern era for these artists. And in 2019, the post-human, cybernated body of the cyborg is more relevant, and more needed, than ever before. The cyborg and its utopian fluidity and possibilities posit the most suitable regalia for rising above the dystopia.

Main Image: Mariko Mori, Tea Ceremony I, 1994. Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York and SCAI the Bathhouse, Tokyo