Open Letters to Adrian Piper

On the occasion of her MoMA retrospective, six missives to the artist from her peers

On the occasion of her MoMA retrospective, six missives to the artist from her peers

Over her career of more than five decades, the conceptual artist and philosopher Adrian Piper has penned numerous open letters to magazines, editors, critics and others involved in the reception of her art. These statements are politically unforgiving criticisms of her critics: cross-evaluations of the ways in which the artist’s exhibitions and works have been (mis)read. Correctives in the broadest sense, Piper’s missives have included requests to be not referred to in a particular way (Dear Editor, Please don’t call me a –, 2003), unrelentingly circumspect fact-checking (An Open Letter to Donald Kuspit, 1987) or simply observing where others have not (To the Editor of The New York Times, 1990). Key to the artist’s confrontational and participatory forms of art making, these epistolary interventions are works of conceptual art and can be interpreted in the spirit of open debate and public discourse that is central to Piper’s thinking. As she wrote in 1980 about her Four Intruders plus Alarm Systems: ‘My interest is to fully politicize the existing art-world context, to confront you here and now with the presence of certain representative individuals who are alien and unfamiliar to that context in its current form, and to confront you with your defence mechanisms against them.’

Piper’s letters directly call out the patriarchy, misogyny, racism and ignorance that the artist’s non-epistolary works have, in part, addressed and revealed. In our fricative moment, in which individuals fray and flare up against society’s abuses of power on these very terms, Piper’s letters are prescient. They have presaged numerous instances of public-private calls for accountability: Yvonne Rainer’s 2011 letter to Jeffrey Deitch — then director of the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles — about Marina Abramović’s proposed use of young, naked female performers at a gala dinner, for instance; or Hannah Black’s 2017 letter to the Whitney Biennial curators about the inclusion of Dana Schutz’s painting of 14-year-old lynching victim Emmett Till, Open Casket (2016); not to mention the countless institutional disruptions and personal-political retributions of a post-Harvey Weinstein #metoo moment.

‘A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016’, Piper’s current retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, is a homecoming of sorts for the artist, who is now based in Berlin. It is also a call-to-arms: at stake in the artist’s work is the possibility to speak or be called out, to confront and intervene, and for solidarity and friendship to exist in tandem with participation and debate: in short, for the possibility of a ‘confrontation between the self and the other’, as Piper described in A. ~A (1974), her parameters for the work Just Gossip. Chiming with the urgency and spirit of Piper’s invectives for open critical debate, participation and intervention, frieze presents a series of open letters to Adrian Piper from six artists and writers.

I always do this thing at airports where, once my flight has been called, I wait until the boarding queue gets smaller before getting up, hanging about until the very last second. Once again, I’m doing just that: peering above my laptop occasionally to see how far along people are and who has crossed the line into the area from where you can’t turn back. Yet, on this occasion, I am so engrossed in reading that the line of passengers before me shrinks and shrinks until it disappears but, still, I persist in reading. Something about what I am experiencing matters more than the flight, matters more than where I am expected to be. I race through this last sentence: ‘So, no matter what I do or do not do about my racial identity, someone is bound to feel uncomfortable. But I have resolved it is no longer going to be me.’ I am reading your text ‘Passing for White, Passing for Black’ (1991). Predictably, when, laptop folded hastily underarm, I present myself to the attendant who’s been eyeing me disquietingly, the gate is closed.

It would so happen that, on my way back from that flight, or some flight shortly thereafter, I’d present my Italian passport to the guard at the airport and he would take an unusual amount of time looking at it, inspecting the photo page with unwarranted diligence. When, having lifted his eyes from the passport, he asks me where I was born, I’m struck raw. He spends more time leafing through the empty pages and says: ‘Your name, your name threw me off.’ I think of these two incidents, unrelated, and I think of being ambiguous, of being not-quite, of being a light-skinned Arab, an Italian whose last name is threatening, who can’t quite speak either language. I think of how you brilliantly describe that position of slow banishment from both camps, from all camps to which we unwittingly belong. Author and civil-rights activist James Baldwin once said: ‘Identity would seem to be the garment with which one covers the nakedness of the self: in which case, it is best that the garment is loose, a little like the robes of the desert, through which robes one’s nakedness can always be felt and, sometimes, discerned.’ I wear your words between that robe and my body, like an armour.

Adelita Husni-Bey

According to 23andMe.com, I am 39.9 percent West African-descended. The results of my genetic testing arrived two years ago by email, the details of my life organized into tidy pastel graphs and charts. They revealed many things I already knew – that I am predisposed to crave bitter flavours, for instance, and to be a light sleeper – and others that I didn’t, such as my being five percent Swedish-descended. I have spent most of my three and a half decades dutifully adhering to the ‘one-drop’ rule – that rigid plantation custom of hypodescent, arriving at an essentialized racial identity without much friction – despite suspecting deep down what my test results made plain: the majority of my ancestry is ‘Broadly Northern European’.

As the son of a driven, high-achieving, teak-toned ‘black’ father from Galveston, Texas, and an unusually unprejudiced blonde mother from San Diego, California, I somehow didn’t think much about the tenuousness of my own racial classification until I married a Frenchwoman, moved to Paris and became the father of a hilarious, towheaded, blue-eyed child. Like you, I left the US for Europe (slightly earlier, in 2011) and – in the great tradition of Josephine Baker, James Baldwin and countless nameless GIs – found the wiggle room to make my life outside of America’s stifling racial binary. I had always understood that – in addition to the attributes we project – our ancestry conditions the image of ourselves that society reflects back. Growing up, despite the presence of my ‘white’ mother, living with my father effectively certified me as ‘black’. What I did not understand is that our offspring have the capacity to reach back and reshape us. I suppose this is why some Jews say it’s not whether your grandparents were Jews that makes you Jewish, it’s your grandchildren that seal the deal. The birth of my alabaster-complexioned, though 19.95 percent West African-descended, daughter four years ago, shattered whatever racial ignorance – or, paradoxically, innocence – I had left in me. I have been trying to write my way through these circumstances ever since.

Which is why my belated discovery of your work came as such a revelation. In ‘Passing for White, Passing for Black’, you write: ‘I’ve learned that there is no “right” way of managing the issue of my racial identity, no way that will not offend or alienate someone, because my designated racial identity itself exposes the very concept of racial classification as the offensive and irrational instrument of racism it is.’ This is an insight I have intuited but that I suspect my daughter will inhabit as you describe. The trick of race, though most perceptible at the margins, is a trick against all of us. A pie chart cannot tell me who I am – or anyone else, for that matter.

I realize now that you beat me to it by a few years, but I want you to know that I have also retired from what the writer Stanley Crouch described most aptly as ‘the all-American skin game’. Maybe, just maybe, if there are more of us out there willing to do the same, we will at last arrive at the point where we can finally face each other – and ourselves.

With my sincerest thanks for signalling the way ahead,

Thomas Chatterton Williams

After you critiqued my work, I stopped making art for two years. We were in Switzerland at a summer academy. You were a visiting artist; I was young and amongst other ‘emerging artists’. I was privileged to show you a series of mobile-phone jammers I had made for an exhibition there. You said that I had not considered the safety of the audience in jamming their communication signals.

Later that night, while at dinner, you went out of your way to speak with me again about the work. Perhaps you could sense that I was in crisis and, at that moment, you told me that you appreciated the subversive nature of the work. You reiterated, however, that you felt that it did not take responsibility for its own activity. After I recovered, I asked you if I could publish ‘Sadhana as a Tapas’ and ‘Brahmacharya, Vairagya, Kaivalya’ in an issue of Veneer Magazine, the publication I edit. In the latter text you write:

One of the great revelations I experienced upon becoming a brahmacharin in 1985 was how much easier this practice in turn made the practice of vairagya: the gradual process of letting go of the many entanglements that bind us to the world of name, form and suffering. I don’t claim that it became easy, just easier. Before, I obsessed constantly about things, situations, people, relationships and objectives that did not develop in accordance with my plans. I also expended an enormous amount of energy in actively man-aging, guiding and trying to control them accordingly. Since, of course, none of these states of affairs were, in fact, under my control, their fulfillment or frustration of my plans, desires and managerial manipulations caused constant psychological and emotional turbulence that my sadhana just barely contained. (Veneer Magazine, 5/18, 2009, pp. 149–150)

At the time, I was struggling to understand the maintenance of my own health holistically. Comprehending how your yoga practice fit into the context of your life, writing and art also put into relief questions that I had about health interfacing more broadly with institutions. I also asked to publish this spreadsheet (above) that you made. I have spent countless hours looking at this document over the years. It has helped me answer my own questions about why you agreed to let me republish your work in the first place. I cherish your production of that spreadsheet. I think that the decisions you make in your work are brave. I help manage a small art library and your books are the ones that consistently go missing or are returned late. I consider your website to be a very important place. I share your texts with students more than those of any other artist.

Thank you,

Aaron Flint Jamison

Once there was a black man who lived with his wife and child on a meadow under a hard, blue sky. The meadow was endless, stretching far beyond the horizon. No trees. No mountains. No buildings. No humans. Beneath the meadow, just below the skin, was a machine that cognated every word, waft and thing in the world.

One day, like every other day, the black man was tilling his garden. His brow was covered in sweat. Reflected on the surface of the droplets many times over was the image of his child walking slightly behind him dropping seeds into the furrows. Almost immediately, birds swooped down out of the blue – almost as soon as the seeds left the child’s hand – gobbling each and every seed as well as bits of flesh leaving small drops of angry red behind. The man and child continued as if oblivious but they conjured each lost seed each swooping thief each wound bereft each poisoned droplet – the coming hurry of winter. They could hear the machine grinding beneath them. Sometimes loud sometimes imperceptible sometimes like flowing water sometimes the space between two atoms some-times a thin mechanical sob. The sun expired against the blue. The black man and child gathered their tools and trudged home. As they walked, it began to snow. Large grey flakes like dryer lint. This meant it was time to talk. The father began:‘Tell me the story.’

‘Everything is in service to everything else but some things –’

‘Rebel.’

‘The meadow believes it cognates, what if not?’

‘And so –?’

The lint fell. The child continued:

‘What what if a bird say a whole flock of birds a whole knot of birds were to eat seed after seed then flying back into the blue causing the white causing the white causing a a a grave to fall down upon the entire earth, what what what then?’

‘And so –?’

Out of the squall of falling dust a mirage. They were surrounded on all sides. Hemmed in by a band of large scruffy hares bristling with great pretty eyes and wearing colourful pleated jackets. The black man stiffened, hiding the child between his strong thighs, he lunged he lunged too late too little too late. For the child. Too late. For already a cottontail was disappearing down into a burrow deep beneath the meadow cry cry cry blood with child in tow.

For several days, the wife waited carving this story into the surface of the kitchen table with the fingernail of one hand. She and the table were silhouetted against the horizon. On seeing the black man come trudging, she walked toward him. On seeing the absent space beside him she threw herself onto his chest over and over and over again. For one hundred million years the black man and his wife were inconsolable until one day in 1968 they began to receive bits of correspondence that always began: ‘I am fine,’ and ended: ‘Adrian Martha Stewart Piper’.

Pope.L

Kameelah Janan Rasheed

When I received the invitation from frieze to write an open letter to you, timed to coincide with your exhibition at MoMA, I was thrilled. I may have accepted a fool’s errand: attempting to pay homage to you utilizing a format that you have employed incisively and powerfully for years. Your Dear Editor, Please don’t call me a – (2003) and To the Editor of Art in America (2001) are brilliant uses of the open letter as a radical conceptual form. They make me worry that I may appear as an accomplished but clueless guitarist attempting to honour Jimi Hendrix by playing for him. But I have accepted the task.

In taking it up, I instantly ran into some of the problems you have critiqued in your open letters. The invitation to write stated, in part: ‘We would like to invite you to contribute an open letter to Adrian Piper as part of this series, which will run as a single feature in the magazine. The letter might comment on an aspect of Piper’s work – black identity, passing, resistance, protest, photography, performance, exclusion/inclusion from disciplines, for instance – in any way you like.’

The phrasing of this request tends to misidentify your concerns and your approach in just the way that you have critiqued. It framed the way I was intended to consider your art and it undermines understanding the radical nature of your work. A term like ‘black identity’ cannot encompass what it means to bring the Rodney King beating and the response of George H.W. Bush into the art world as you did in 1992. Nor does ‘passing’ encompass calling people out for racist comments made in your presence. It doesn’t encompass challenging the entire concept of race and your relentless pointing out that in America miscegenation is the norm.

Furthermore, the listing of prompts omits gender. In The Mythic Being (1973) you walked the streets apparently as a male. The speech bubbles in the collages that you made of this work raise complex issues of male power, gender, sexuality, racism and public space: ‘Get out of my way, asshole.’ ‘Say it like you mean it, baby cakes.’ They are particularly relevant today. In an era when women are vigorously resisting sexual harassment and rape, I want the readers of this letter to view and think about gender as an important area of your work to address. The invitation named you as a conceptual artist. But listing photography and performance as media – not to mention the list format overall, in suggesting how to write about your work – serves to separate a cohesive practice. You are a conceptual artist even if you deploy a variety of formal strategies to achieve your artistic aims.

I am wary of adding to the litany of inaccurate writing about your art – which you have gone to great lengths to correct. Selective miscategorizations of your practice are at the heart of a limiting misunder-standing of your work. It’s not just that individuals get aspects of what you do wrong. Collectively, publications and writers with even the best of intent often don’t do the work to really engage your art. It is difficult to have one short letter or even a collection of letters address the range of your practice and its importance to me. What would it take to give readers that ability to explore the breadth of your ideas? Whom do you admire? Whose ideas do you value (other than David Hume, Immanuel Kant and John Rawls)? Whom would you have liked to write you an open letter? Given all of this, I hope you will consider the following:

Please keep demanding to be thought of as an artist.

Please keep demanding to be thought of as a philosopher.

Please keep demanding to have yoga thought of as part of your practice. (Even if I don’t understand this and personally sometimes unintentionally deny this to you.)

Please keep demanding to be addressed on your own terms.

Please keep demanding that critics actually look at your art.

Please keep demanding that critics put your work in an art-historical context.

Please keep demanding that critics write about your actual work.

Please keep making art that makes people uncomfortable because of their racism.

Please keep making art that makes people uncomfortable because of their patriarchy.

Please keep showing art that makes people uncomfortable because of their racism.

Please keep showing art that makes people uncomfortable because of their patriarchy.

Please keep working on a variety of ideas.

Please stay complex.

I look forward to seeing your MoMA show. I hope that it provides a good overview of your practice.

And I hope that critics and editors seriously engage your work when writing about it.

Best regards,

Dread Scott

P.S. I understand that you have ‘retired from being “black”’. At a time when I and other artists tend to affirm our Blackness and give ourselves permission to speak about it, your statement is characteristically challenging. I look forward to how this affects your work, if at all, and to seeing/reading/hearing more of your thinking on this.

Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965 - 2016, runs at MoMA, New York, until 22 July.

This article appears in the print edition of frieze, May 2018, issue 195, with the title Going Postal.

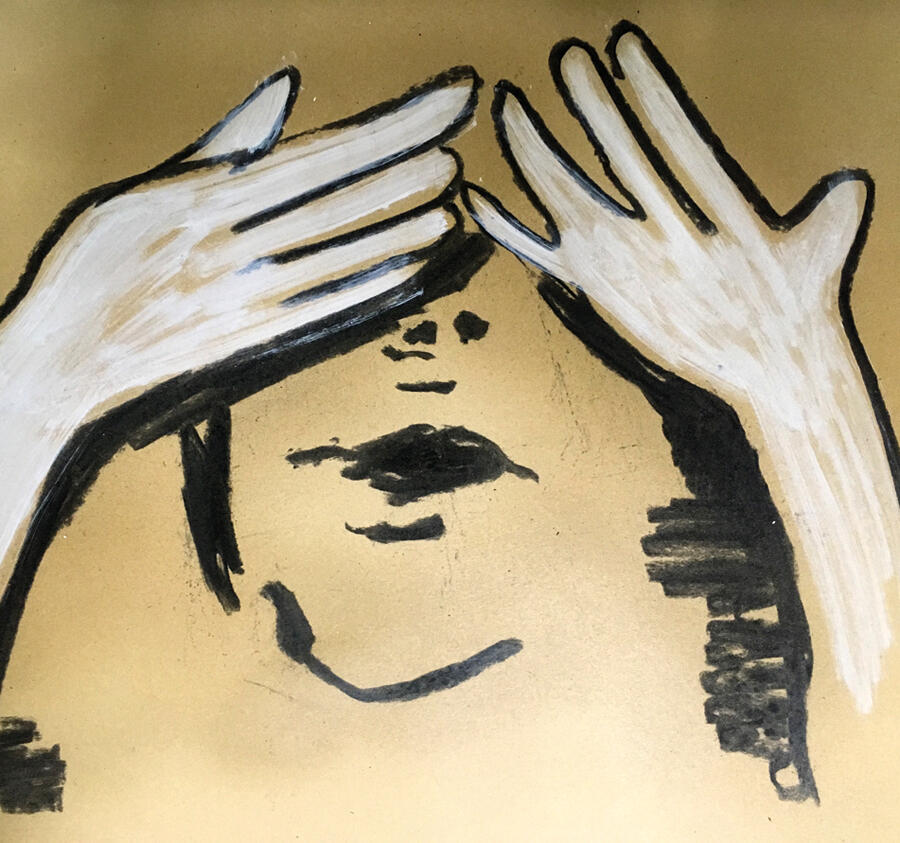

Main image: Adelita Husni-Bey, Untitled- Letter to Adrian (version II), (detail), 21 cm x 29 cm, pen, ink and gouache on paper