Echoes of Vietnam in the American South

Four artists share how their connections to the Vietnamese diaspora – from New Orleans to Ho Chi Minh City – shape their storytelling

Four artists share how their connections to the Vietnamese diaspora – from New Orleans to Ho Chi Minh City – shape their storytelling

Terence Trouillot How have your personal connections to the Vietnamese diaspora influenced your artistic or professional work?

Christian Ðinh It’s the crux of my work. In 1975, at the end of the American War in Vietnam, my whole family emigrated from Vietnam to Florida, where I was born. I’m a firsthand witness to how the Vietnamese American community has been developing both in Florida and here in New Orleans, where I currently live. This is something I reflect on in my work, aiming to highlight the community and its unique trajectory, which is still evolving almost 50 years after the Fall of Saigon.

Tuâń Andrew Nguyên I’m interested in looking at how colonialism and events such as the Cold War and the American War in Vietnam influenced the movement of people throughout the world – particularly since my own family was directly impacted by one of those migrations.

Arlette Quỳnh-Anh Trâǹ I was born in East Germany – a country that doesn’t exist anymore – and, when I returned to Vietnam as a child with my family, my par- ents decided to migrate from the North to the South. At the time, I was still in primary school, but I can still clearly recall most of my friends emigrating overseas. As a consequence, I’m very interested in the implications of being from the so-called Third World.

From the 1920s, Vietnamese revolutionaries and intellectuals studied abroad, returning influenced by Western, Japanese or American thinking. Key figures like Ho Chi Minh and Ngo Ðinh Nhu travelled extensively before shaping Vietnam’s political landscape. These individuals and their journeys fascinate me. They left with dreams and returned with expanded visions. Their aspirations, whether realized or not, inspire my art and, through my work, I aim to continue their legacy of imagination and vision.

TAN When we think of a diaspora, we often perceive it as singular. Yet, the Vietnamese diaspora – which ultimately began as a consequence of the Cold War, decades before the end of the American War in Vietnam – is one of the most complex.

Tuan Mami Personally, I am not focused on this notion of nationality. I don’t really engage with the political aspects of Vietnam or the Vietnamese diaspora. I’m more interested in working closely with communities. In my series ‘Vietnamese Immigrating Garden’ [2020– ongoing], for instance, I work with and live among Vietnamese immigrants in different locations – Taiwan, Japan, the US, Europe – and each community has a unique perspective on Vietnam and its culture.

When I came to New Orleans to do research for the next instalment of ‘Vietnamese Immigrating Garden’ at Prospect.6, I was worried because my family is from Hanoi. I knew that the New Orleans Vietnamese community was staunchly anti-communist, but I didn’t expect that, within minutes of meeting me, they’d be asking: ‘Are you communist? Are you working for communists?’ It was shocking but I immediately explained that I wasn’t doing political research, I was interested in learning about their lives – how they maintain, adapt and develop their culture in a new environment – to present in my work a perspective that closely echoes their daily reality.

It didn’t take me long to connect with the community, gaining an insider’s perspective and experiencing their warm welcome and protection. Compared to other Vietnamese immigrant communities around the world, the one in New Orleans seems to have retained a remark- ably pure form of Vietnamese culture and created a close-knit structure that offers both economic and spiritual support. Living together in a somewhat isolated area of the city, in the Village de L’Est neighbourhood, they exchange goods and services, maintain traditional practices and re-create their old way of life in a new setting. The New Orleans Vietnamese community has influenced my thinking, showing me how maintaining identity through a new model based on old traditions can be powerful. Most community members here are ‘boat people’, who arrived in the US at a very young age. Yet, they were able to preserve their culture more effectively than in other places I’ve visited.

The New Orleans Vietnamese community has influenced my thinking, showing me how maintaining identity through a new model based on old traditions can be powerful.

Most of the Vietnamese immigrants in New Orleans have undertaken two refugee journeys. More than 90 percent come from North Vietnam and are Christian. When the communists arrived, and French colonizers left the North in 1954, they were forced to flee to South Vietnam. Years later they migrated to the US, starting from 1975. Yet, despite limited childhood memories, their North Vietnamese culture still influences their daily lives, especially in their cuisine. I’m drawn to how these invisible cultural layers persist and merge with new experiences.

TT Christian and Tuâń Andrew: you both work in sculpture, adapting or alluding to objects that are loaded with meaning – from wartime artillery shells and bombs to Vietnamese nail salon mannequins. Are there parti- cular aspects of the Vietnamese American diasporic experience that you find especially compelling or challenging to convey?

I'm a firsthand witness to how the Vietnamese American community has been developing both in Florida and here in New Orleans.

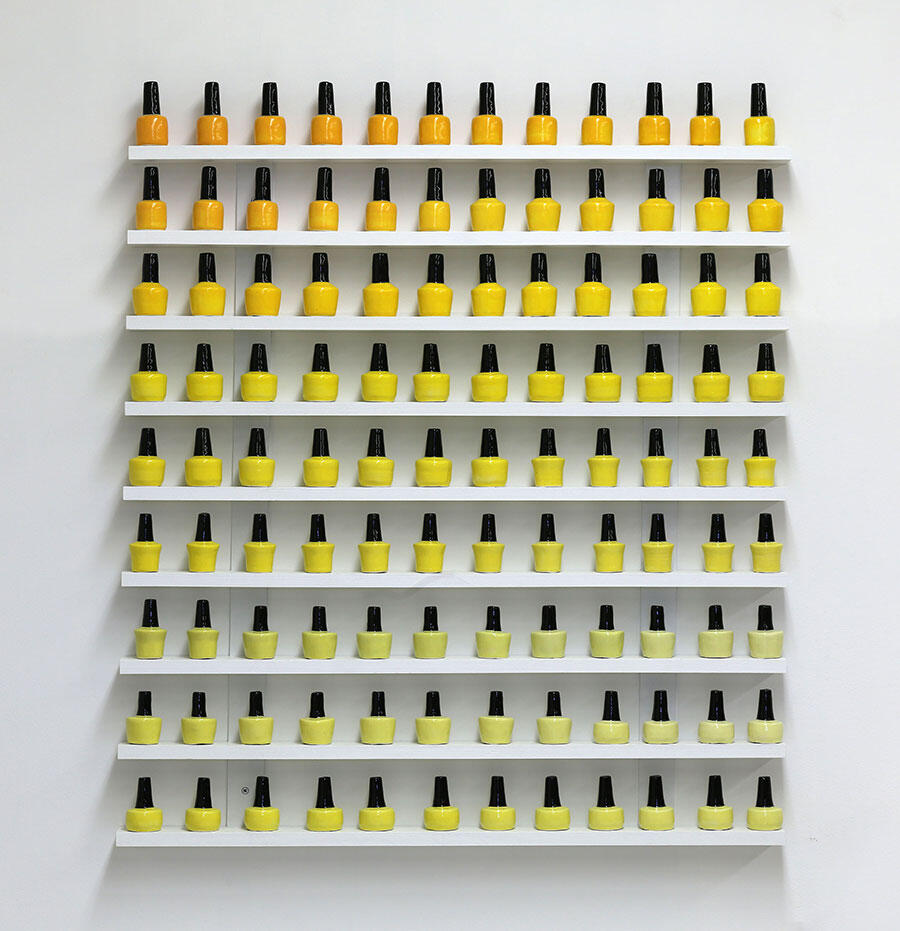

CD My work focuses on items significant to the Vietnamese American community. I take familiar images and place them in contexts that alter their mean- ing, making them universally relatable. For instance, in my series ‘Nail Salon’ [2020–ongoing], I use recognizable items, like plastic mannequin hands, overlaying them with a mixture of Vietnamese, American and French cultural elements. From the very start in the late 1970s, a large reason Vietnamese refugees found nail salons accessible to have a career in was because of the minimal English-speaking requirements. The work environment was adaptable to the language barriers that the refugees dealt with, and still is five decades later. I saw the plastic mannequin hands as something more than a mundane object, but a tool used for communication. I wanted to elevate the importance of the object and the role it plays for the nail salon workers by casting them in porcelain. I was interested in the history of the porcelain trade, referring to ceramic goods (dishware, pottery, sculptures) stemming from China and southeast Asia. I wanted to relate these qualities of value, beauty and preciousness to these porcelain hands. My sculptures aim to create a universal language, highlighting the Vietnamese community’s integral role in American society – having a tremendous impact on what is now a multi-billion-dollar industry in the nail salon business. Though often overlooked in the media, the Vietnamese American experience has become a fluid part of the US, particularly in the South.

TAN I was born in Vietnam but landed in the US at a very young age. Even then, I started to understand the importance of objects in relation to the stories that were being circulated within our community. This was particularly true of photographs, which were very rare in my family: I don’t have any photos of myself as a child. So, I think my approach to artmaking really stems from this curiosity about the relationship between object and narrative. I’ve been working with unexploded ordinances from across Vietnam, making sculptures and mobiles from old bombs and artillery. But I’ve also been looking at the objects people made in refugee camps after the end of the American War in Vietnam, like the one on the island of Pulau Bidong in Malaysia, or Batu Malang in Indonesia, which was a major processing centre for refugees. I’m fascinated by the imagination people imbued into these humble objects, which were made out of whatever they could find, while they were in this transitional period of statelessness between their native country and wherever they might be rehomed.

TT Arlette, as an artist who wears many other hats – writer, researcher, curator – how do you navigate the inter- section of Vietnamese identity with Southern American culture? How does your work, which is focused on world-building and the idea of Third World utopias, fit within the context of the American South?

AQAT I’ve noticed a lot of similarities in my experiences of these different regions. Being in the American South is like standing at a crossroads: you have this opportunity to explore numerous avenues of influence. My first encounter with the idea of the American South was during my teens. I was looking at Cajun cuisine in Louisiana and I thought: ‘What? French food in America, with a hint of Caribbean?’ It tasted very familiar, similar to the cuisine of South Vietnam. More than 1,000 years ago, long before the borders of Vietnam were established, early civilizations in the region traded with Greeks, Romans, Chinese and Indians. There are traces of aesthetic influences from Roman and Greek civilizations in Vietnam, such as decorative patterns in jewellery and object designs. I think this idea of being ‘remixed’ and constantly challenging one’s identity is, similarly, a condition of being in the Global South.

TT As artists, do you feel that your work contributes to cultural preservation or community survival?

CD A lot of my work revolves around this idea of community and I’m always looking at how to concretize the things I’ve learned into my practice. That’s why my most recent body of work, the ‘Nail Salon’ series, is entirely comprised of ceramics. By crystallizing the Vietnamese American experience into this medium, I’m creating a time capsule – a ceramic archive – that preserves experiences for future generations to unpack and understand.

AQAT Survival, I believe, intertwines with the desire to be remembered and understood. This theme is central to my video, The Curator Ghost [2024], for Prospect.6, which is a fictionalized story inspired by the life of Nghiem Tham – a Vietnamese curator who organized the exhibi- tion ‘Art and Archaeology of Vietnam: Asian Crossroads of Culture’ at the Smithsonian in 1960. This touring show was South Vietnam’s inaugural cultural presentation on the global stage and, in contrast to previous colonial contexts, marked the first instance in which the country exerted control over its international representation.

Being in the American South is like standing at a crossroads: you have this opportunity to explore numerous avenues of influence.

In 1975, Nghiem Tham sent his family abroad but opted himself to stay in Vietnam. His journey – initially from North to South, followed by a period spent studying overseas and, ultimately, his return to Vietnam – demonstrated his resilience. In creating the film, I focused on capturing the specific accent of those from North Vietnam who migrated South in 1954. This attention to linguistic detail resonates with the Vietnamese diaspora’s desire to retain their cultural identity, as seen in communities like the one in New Orleans. Tragically, Nghiem Tham was later murdered in 1979 for resisting historical revisionism, in a heartbreaking example of how Vietnamese identity has been preserved through personal sacrifice.

TAN This concept of a division between North and South is something that many Vietnamese people still can’t overcome. There was a mass movement of people from the North who were persecuted for being Catholic or because they were landowners, and so on and so forth. But there was also Tâp Kế t – the movement from South to North of people who believed in and fought for communism. Because the political ideologies of that split were so strong, they persist to this day. Many people in the New Orleans community, especially in New Orleans East, are from the North originally. But their accent is an older northern accent, pre-1954. So, when Tuan Mami went to meet them and spoke Vietnamese with the Hanoian accent he had learned from his parents, he was easily identifiable as not being descended from those who emigrated in 1954. It’s very interesting.

AQAT That is something I was also very conscious of when making The Curator Ghost: only a Vietnamese audience would recognize that subtle distinction in accent.

TM This notion of cultural preservation is also present in my own work, but it exists more in the form of fantastical thinking. For instance, one old man in New Orleans told me that he had left his home in Vietnam when he was five or six years old and never returned. But, when I asked him where he’d go if he had the chance to go back, he immediately said the place he was born. So, I asked him: how would you find it? And he responded: ‘I believe I could find it easily.’

TT How does generational trauma manifest in your storytelling?

TAN I’m more interested in how storytelling can be used to fill gaps, enabling us to embark on a journey of healing. That’s where, for me, the potential of storytelling becomes really powerful. I relate a lot to what Arlette is saying about speculative narratives and the possibilities that exist within them to go beyond the stories that we see as defining us and to find, instead, alternative narratives that can redefine us – or help us redefine ourselves – as whole beings. Because, of course, the whole point of the colonial project was to fracture us, to make us ‘unwhole’ and subhuman.

The number of people displaced globally over the last century or so is mind-blowing. The 20th century truly was the era of the refugee. Anywhere you go now, you will come across people with a migration story, and that has helped me find entry points into numerous conversations and collaborations across various projects, throughout different geographies and histories. What you come to discover is that, ultimately, these histories are very similar because they all emerged from that same beast of a thing: the colonial, capitalist, extractivist machine that has brought us to where we are now.

TT Tuâń Andrew, your exhibition earlier this year at Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona featured the video The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon [2022], in which a young Vietnamese woman creates art from artillery shells while addressing her mother’s trauma. Exploring healing and intergenerational communica- tion, the work connects to Tuan Mami’s observations about speculative storytelling, or what theorist Saidiya Hartman, in her essay ‘Venus in Two Acts’ [2008], terms ‘critical fabulation’. I find this concept fascinating, particularly for immigrant communities emerging from colonialism. Rebuilding narratives from erasure through research and speculation is compelling.

The whole point of the colonial project was to fracture us, to make us ‘unwhole’ and subhuman.

TAN We think of memory as a space that needs to be addressed for any constructive process of healing to begin, but we also have to remember that forgetting has been used very effectively as a form of survival. And that’s what PTSD is: the different forms of distress and amnesia that stem from these moments of trauma. There were communities of Cambodian women who suddenly went blind in the 1980s, for instance, during the violent regime of the Khmer Rouge. Known as ‘functional blind- ness’, it was a self-preservation mechanism because they simply couldn’t bear to see the horrors anymore.

One question that The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon raises is: why do we feel displaced if we haven’t ourselves experienced migration? The film’s narrative shows the protagonist having a radical breakthrough in terms of her relationship to her mother’s trauma and the intergenerational trauma that she’s having to deal with.

TM I agree with Tuâń Andrew that both strategies are useful – essential, even – for survival. However, they also intertwine with one another. For instance, there’s an 85-year-old man in New Orleans who still has strong memories of his journey. On my last day there, someone gave me the chance to interview him. He lives alone in a big house, which is quite tough for him. By the end of our talk, he was almost in tears. He said that, for many years, he had tried to forget and not talk about history. But, on that particular day, he felt thankful that someone came to listen to his story. He told me that, as his generation passes away, he felt his story should be recorded and recounted for future generations. Now, as Prospect.6 launches, I’m not only excited to see the works we have made, but also to reflect upon how we can contribute to different generations and to show history not as a grand narrative, but through individual stories.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 247 with the headline ‘Humble Objects’

Christian Việt Ðinh is included ‘Prospect 6: The Future is Present, The Harbinger is Home’ is on view at The Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans from 2 November – 2 February 2025

Tuan Mami is included ‘Prospect 6: The Future is Present, The Harbinger is Home’ is on view at Xavier University of Louisiana Art Gallery, New Orleans from 2 November – 2 February 2025

Tuan Andrew Nguyen is included ‘Prospect 6: The Future is Present, The Harbinger is Home’ is on view at New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA) Sydney and Walda Besthoff Sculpture Garden Sculpture Pavilion, New Orleans from 2 November – 2 February 2025

Arlette Quỳnh-Anh Trần is included ‘Prospect 6: The Future is Present, The Harbinger is Home’ is on view at Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University Woldenberg Art Center, New Orleans from 2 November – 2 February 2025

Main image: Arlette Quỳnh-Anh Trâǹ, The Curator Ghost (detail), 2024, video still. Courtesy: the artist and Prospect.6