Thomas Kilpper

The new Tate Modern sends gleaming signals of wealth across the river Thames. But as you walk towards Orbit House, an abandoned 60s warehouse only a few blocks away, second-wave Modernity rapidly gives way to a fractured jumble of old buildings. Sooty brick houses, dented garage doors and new, cheap, office shoeboxes all come together in a confused mish-mash of railway bridges and dark side streets. Orbit House is waiting to be pulled down to make way for an office complex already gilded with the image boost that the new museum has brought to the area. Its facade of glass and blue panels was obviously once pretty impressive. Now it looks weary, as if every breath of energy has been exhaled; a ghost house.

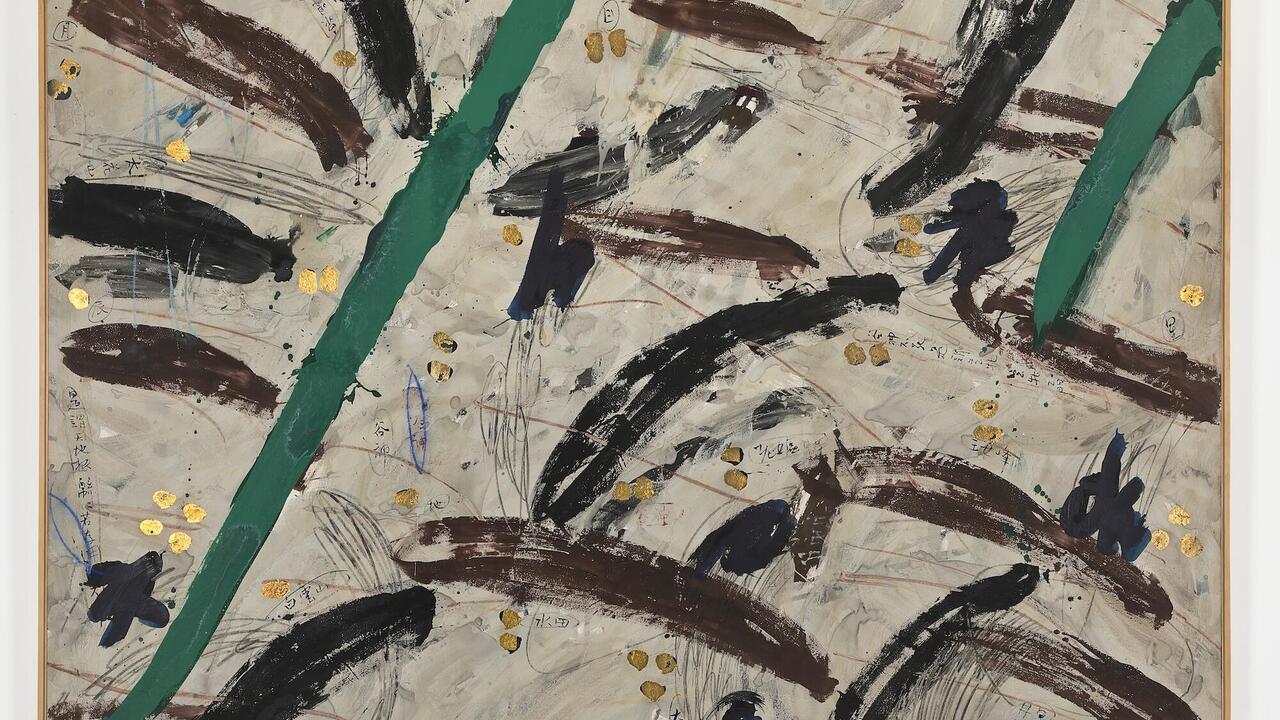

Orbit House actually has a sort of ghost: a lively German who goes by the name of Thomas Kilpper. On the building's eleventh floor, the lights are on. Although it's odd to discover a herringbone pattern parquet floor in such a place, it's even odder to discover that it has been covered in carvings. Made with a small chainsaw, more tattooed than hacked, they link an array of familiar faces from Hitchcock to Hitler. You walk on them as if you are walking on a beach looking for flotsam, nudging them with the tip of your foot, timid and concentrated.

Kilpper initially chose the building for formal reasons: he had been searching for a large wooden floor in a condemned building to create a vast wooden relief (as he has done previously with a US army basketball hall near Frankfurt). But Orbit House is more than a random site - it's as if an old-fashioned printing process short-circuited with Warhol's 15 Most Wanted Men (1963) and Jörg Immendorff's neo-Expressionist Café Deutschland (1983).

Orbit House was not only the temporary home of the Oriental Department of the British Library (the proud owner of the world's oldest dated wood engraving: a Chinese image of Buddha from 868 AD that includes the symbol that, reversed, became the Nazi's Swastika), but also, until the mid-80s, a secret printing press for the Ministry of Defence. It was built on the ruins of an old Protestant church that became a boxing ring in 1910 and attracted audiences in their thousands. For years it was used occasionally for church services, or productions of Shakespeare's plays. Hitchcock shot some scenes in it, and a performance of Richard Wagner's Ring Cycle (1851-74) was planned before the Germans bombed it in 1940. The site's history may seem to be a random succession of disconnected occurrences, yet the closer you examine it - which is what Kilpper has done - the more it seems to embody a strange historical conspiracy.

Kilpper attempted to (literally) fill in the blanks with his exploration of what Britain has meant to him during his artistic and political coming of age in the 70s and 80s: the convoluted history of war, colonialism and religion reflected in images of Navy brides flashing their breasts to departing sailors during the Falklands war, or of the IRA's Bobby Sands on his hunger strike, for example. Sometimes Kilpper's images reflect his personal cosmology, as when friends appear amongst his pantheon of historical figures, either because he quite simply likes them or, as in his carving of Madonna, because they have some relationship to London.

The artist's blurred focus mocks official histories and reclaims them as personal ones. As the Tate Modern's neighbourhood awaits final cosmetic surgery to erase its war-wounds, Kilpper, like a mapping termite, won't let the past be buried.