Lights, Camera, Painting

Stefan Hayn’s new film STRAUB and his painterly approach to documentaries

Stefan Hayn’s new film STRAUB and his painterly approach to documentaries

In the summer of 1974, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet made Moses and Aaron, a film based on Arnold Schönberg’s opera of the same name. In keeping with their trademark emphasis on live sound they filmed in an outdoor amphitheatre in Italy. While on set, Huillet kept a journal in which she logged practical, lackaday details: the Eastmancolor 5254 film stock they used for the last time before switching to a new industry standard; the Fisher sound boom that allowed a microphone to be positioned just out of frame (even for long shots); even the problem of finding toilets for the cast after local farmers stopped granting access to their houses.

Huillet’s journal – a translation of which was published by the German magazine Filmkritik in 1975 – is one of the key elements of Stefan Hayn’s film STRAUB (2014), in which excerpts from the journal are read by two female actors in voiceover. The simple title is programmatic: in the European auteur cinema of the postwar era (French New Wave, New German Cinema), the fame of Straub-Huillet (or sometimes just Straub) was second only to that of Jean-Luc Godard and Robert Bresson. You could call the position of Straub-Huillet paradigmatic for the time, characterized by their embrace of the technical possibilities of modernist cinema: using the apparatus at their disposal to take the boundary between reality and medium to the point of Brechtian estrangement. Straub-Huillet films were anti-naturalist by way of their strict technical naturalism. This is underscored by the peculiar lofty tone in their films, which used adapted texts by Friedrich Hölderlin, Franz Kafka or Elio Vittorini, as well as Brecht himself.

For Hayn, a filmmaker and painter, currently on a postgraduate programme at Berlin’s Universität der Künste (UdK), referring to Straub-Huillet is a way of positioning himself as an artist between different media. His previous work took a dialectical approach: Weihnachten? Weihnachten! (Christmas? Christmas!, 2009), for example, is a documentary that focused on Berlin’s multicultural Neukölln district shot in the style of Direct Cinema – a genre similar to cinéma vérité – to explore debates concerning the role of the welfare state and issues of social cohesion. STRAUB, on the other hand, clearly works on a more meta level, Hayn seeks to relate to Straub-Huillet not by trying to emulate them, but through a strategy that switches between mimicry and originality. One aspect that appears imitative is the way he places the reading of Huillet’s journal alongside a second text that is heard in French: passages from L’Espèce humaine (The Human Race, 1947; 1998) in which Robert Antelme recounts his incarceration (and narrow escape from death) at the Gandersheim concentration camp – an outpost of Buchenwald – in 1944.

Existing texts are always a constitutive element of Straub-Huillet’s films. The relationship between image and spoken word is never classically complementary – language clearly has primacy. The result is a special kind of literary adaptation that doesn’t try to meet the standards of a radio play (smooth language, narrative flow) nor of literary cinema (realistic characters, illustrative images).

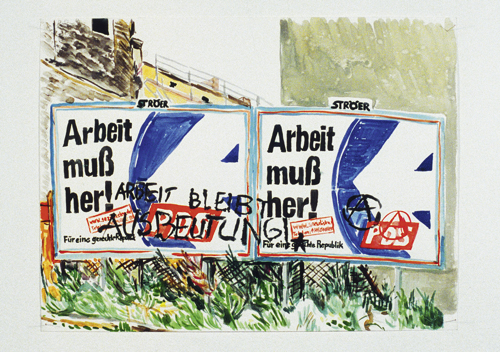

Against this backdrop, in STRAUB Hayn goes one key step further in defining the relationship between image and text, as well as examining his own position within art and film history. Instead of filming outdoors or using pre-existing images to illustrate the texts he draws from, the images in Hayn’s film are comprised of his own large-format oil paintings and drawings. In this way he reverses Straub-Huillet’s procedure: driven by their admiration of Cézanne, they looked for a cinematic form that could be understood as technicized ‘pure seeing’. No footage is used to match Antelme’s texts (apart from a road sign from Gandersheim and a street scene in Paris) nor taken of the Italian locations for Moses and Aaron. Instead Hayn’s visuals are the works he has been making since 2006; by this method STRAUB can also be understood as the continuation of an earlier film, Malerei heute (Painting Today, 2006). This film by Hayn and his longstanding partner Anja-Christin Remmert includes aquarelles of urban spaces and billboards sporting political adverts in Berlin which Hayn began painting in 1998. They represent an incisive shift in documentary practice as watercolours don’t seem well suited to exploring the political messages found during a national election campaign – one which resulted in an SPD/Green party coalition in Germany. But in 2006, when Malerei heute was completed and any high hopes for political modernization in Germany had long since vanished, the scorned figure of the slow painter with his outdated medium seemed particularly apt. STRAUB appears as a second step in reclaiming the possibilities of painting, doing so via the cinema, which replaces the need for a gallery or museum.

One might accuse Hayn of using STRAUB to emancipate himself from an overpowering tradition, presenting himself as an artist coming late to the game (he turns fifty this year). But it would be wrong to understand the result of his work in film – that has dealt with abstracted forms of documentary since his first, Schwulenfilm (Gay Film), in 1989 – as his arrival in painting, even if the step towards large-format oil painting points that way. Even after having seen STRAUB, it remains unclear whether these pictures would be more at home in a gallery or museum context (as in the exhibition at Heidelberger Kunstverein in 2014 where, interestingly, Hayn was shown together with Harun Farocki) or whether they are better positioned within film, a context beyond painting’s own traditions. In any case, one of the film’s most striking scenes hints towards Hayn picking up the history of painting in more than one sense: footage shows him lugging a Jesus torso around, an allusion to Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, and so to a painting tradition whose expressivity pushed figurative realism to its limit. Here we see that unlike many other contemporary filmmakers in the German-speaking world, Hayn is aware of modernism’s own history. Yet equally he takes modernism to its own extremes, not least in the soundtrack (STRAUB features the music of both Schönberg and Paul Hindemith). So Hayn carries tradition like a burden, but, as STRAUB impressively shows, he carries it out into the open.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell

STRAUB will be screened in early April in Berlin (Kino Arsenal & fsk Kino) and in Munich (Werkstattkino).