The Alchemist

Hot metals and cool minimalism: the transformative processes of Raphael Hefti

Hot metals and cool minimalism: the transformative processes of Raphael Hefti

Mercury, magnesium, aluminium, titanium, brass, bronze, iron, copper, silver, gold: there is a richness of history and allegory imbued in the metals of the world. We like to tell our story – via myth, or scientific narratives – through metals because we understand them through their utilization and transformation by our desiring bodies, through our great and ungreat civilizations, by those hotly named metallurgists: consider the Bronze Age, the Iron Age, the Ancient Greeks’s blacksmith-god Hephaestus, the Telchines and Dactyls. Yet the depth of language and narrative (process, in other words) that surrounds metals and their technological and poetic employment is usually at odds with the apparent simplicity and discrete autonomy of their oft-manifested forms – as tools. (So deft and pointed that word.) Raphael Hefti’s strangely singular, subtle body of work – in which he grapples with the properties and processes of manufacturing (metal as well as glass and mineral) – likewise resides on the shifting plates of this paradox. His crush on protean industrial material processes, which he delicately perverts with an inventor’s recklessness, seems to belie the strangely refined aesthetic qualities of his resulting works; his sculptures and photograms can appear too beautiful and expressive by far to fit in with his more manically exacting scientific methodologies. If a certain aesthetics of form – coolly minimal, expertly attractive – is not Hefti’s goal, it remains the material fact by which his audience can trace back (or be led astray by) the story of the making.

This story of the Swiss artist’s practice – developed chiefly in the two cities in which he lives and operates, London and Zürich – is an inherently social one (an overused term, yet useful). While industrial processes are supposedly in the game of bettering society, furthering a luxury of living, Hefti’s manipulation of these processes, the seeming unusefulness of the material products he creates, is a bait-and-switch. The pleasure in deviating procedures and skilled communities is very much his endgame: the pleasure he takes in working with industrial technicians and digressing from their careful procedures, and the pleasure he takes in presenting them to an art audience as traces or repositories of this methodology – as art objects of circulation and reception, neither fetishized nor duly cast off. In the contemporary art world we speak easily of labour, of industry, of material, but most of us seldom actually go there. Hefti does, though. One rarely finds him alone in a room, neither the room of his own skills and procedures – he is often in factories across Europe, learning from technicians – nor alone in his studios, which are dependably filled with friends, peers and assistants (for whom he regularly cooks, another kind of transformative process).

But back to metal and mineral. Consider his exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary in the UK last year, which brought together recent series, each an experiment with material processes taken too far, delivered in almost outrageously elegant, essentialist form. Three enormous abstract photograms, each cut into three strips, hung from the ceiling, the photo paper curling slightly just above the floor. Bursts of pink, purple, pale violet, the photogram’s ‘image’ a kind of abstraction that we often describe as celestial – comets burning out, say, or black holes framed by stars. (Note here we reach for a metaphor to describe the very event being ‘photographed’: spores burned into another material, photo paper, as an image.) For this Lycopodium (2014) series, the photograms were made in pitch dark as Hefti lit the flammable moss spores of the titular powder – regularly used in fireworks and explosives, as well as for the coating of pharmaceuticals – over entire rolls of colour photosensitive paper. Lycopodium in particular strikes a nearly perfect history for Hefti to draw from: in the early 19th century, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce used the powder to fuel the first internal combustion engine; later he invented photography (View from the Window at Le Gras, from 1826, is his). But Hefti’s Lycopodium images also suggest something else: a collusion of postwar gestural colour field painting and recent abstract photography, aesthetic registers well understood by a contemporary art audience. Part of the strangeness of the artist’s work lies in this: our familiarity with the (high art, creative) aesthetic forms he creates, and our unfamiliarity with the (quotidian, industrial) material processes he uses to achieve them.

Near the photograms was another series of works entited Etched totem (2014). Plates of cast aluminium, copper and zinc that Hefti ‘macro etched’ – a process of etching and polishing – revealing each metal’s singular make-up of crystals. Taking in the small plates’ material abstraction, I remembered that lycopodium powder was used in physics experiments to make sound waves and electrostatic charge visible for observation and measurement. Likewise here Hefti made visible the usually invisible crystals that compose the metal. Still, what was it we were seeing exactly? He has described it as manipulating the sculpture from the inside out, from its very materiality. Was this a story of fabrication estranged from use? Or a series of metal plates in a museum reminiscent of postwar Spanish and American abstract sculpture in all its torpor, pathos and machismo? The series of objects held these circling narratives (of transnational postwar industry, mass production, art and ideology) without quite offering them to you. This vagueness is troubling, irreducible, but might also be transformative.

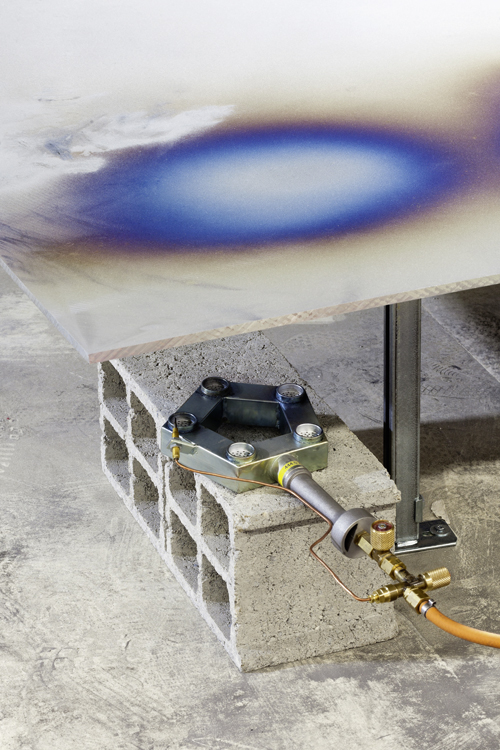

More lucid are series such as the terminally gorgeous Luxar-coated glass panels of Subtraction as Addition (2012–14), which suggest reductionist versions of Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass (1915–23) created by overdoing the industrial formula for creating transparent glass and iridescent as oil slicks. So too a set of 150 one-metre-long poles of attenuated aluminium, copper, steel and titanium, screwed or welded together in lengths of six, with various strange and beautiful colourings occasioned by being heated to extremely high temperatures at various points along their slim length. Titled in a kind of deadpan approximation of the minimalism it suggested, Various threaded poles of determinate length potentially altering their determinacy (2014), the work strikes the balance of stylish seriality and industrial materiality that is Hefti’s calling card, but it also just works, beautifully. Still, the artist, who studied engineering in Switzerland before receiving his MFA from the Slade School of Fine Art, London, in 2011, works in less temperate registers too. Consider the car he accidentally blew up years ago during an Alpine experiment, for which he put on a terror watch list by the Swiss authorities, or the more carefully orchestrated explosions at SALTS, Basel, and Ancient & Modern, London, in 2013, when he filled the galleries with mountains of sand, donned protective clothing and a facemask, then melted steel to liquid, allowing it to run down the dunes like lava in front of flushed audiences, shaping it as it went: formed material loosened, then formed again.

This able movement between the outsized gesture and the intimate, local one can also be located in the artist’s permanent roof installation of coated glass panels commissioned by Fondation Vincent van Gogh, in Arles, in 2014, which turns the glass atrium below into a kind of kaleidoscopic cinema of dappled coloured light, as well as in his show at RaebervonStenglin, in Zürich, the same year, in which he situated approximately 30 tonnes of aluminium in its saleable format (huge blocks spray-painted with relevant technical and commercial information) in the gallery centre, priced at its exact value as raw material on the global marketplace. As in this last work, Hefti’s interest is in making evident and observable the processes – industrial, material, economic, commercial, aesthetic – on which our lives are predicated. More mysterious is the contest between material and form, process and use value, which seems to drive his practice forward. If his kind of minimalism does not simply privilege the object or the material but the material procedure itself, it’s this intervention of subjectivity and sociality – released from the responsibility of inherent objectives, to either material or humankind – that places his work on its firmest, strangest, most experimental ground.