Another Story of Art

What happens when images float free from the text they illustrate?

What happens when images float free from the text they illustrate?

An updated version of E.H. Gombrich’s classic, The Story of Art, has been floating around for a while. That’s not surprising. The publisher, Phaidon, has been reviving The Story of Art since its debut in 1950 (to date, there have been 16 editions and 39 reprints). The most striking feature of this latest edition, from 2006, is the book’s size, which has been reduced from the familiar, large-format paperback to a portable pocket-book. Reducing the size forced Phaidon to make a bold change in the layout: separating the text from the illustrations, which are now grouped together in the latter half of the book. For the first time, the story of art is being told by words without the pictures that animate them.

But the real novelty is revealed by Phaidon publisher Richard Schlagman, who worked closely on earlier editions with Gombrich himself. Since the great art historian passed away in 2001, Schlagman penned the preface for the pocket edition. In it, he reminds the reader about a peculiarity in Gombrich’s initial presentation; his subtle attempt, perhaps, to challenge the traditional subordination of illustrations to text in art-historical studies. ‘The text itself remains identical to that of the 16th edition and all of the images illustrated there are included here,’ writes Schlagman. ‘Only the very astute reader may notice that the small illustration “sign-offs” that the author used previously at the end of each chapter, but did not refer to in his story, are missing from this edition, as in this layout they would have served no purpose.’

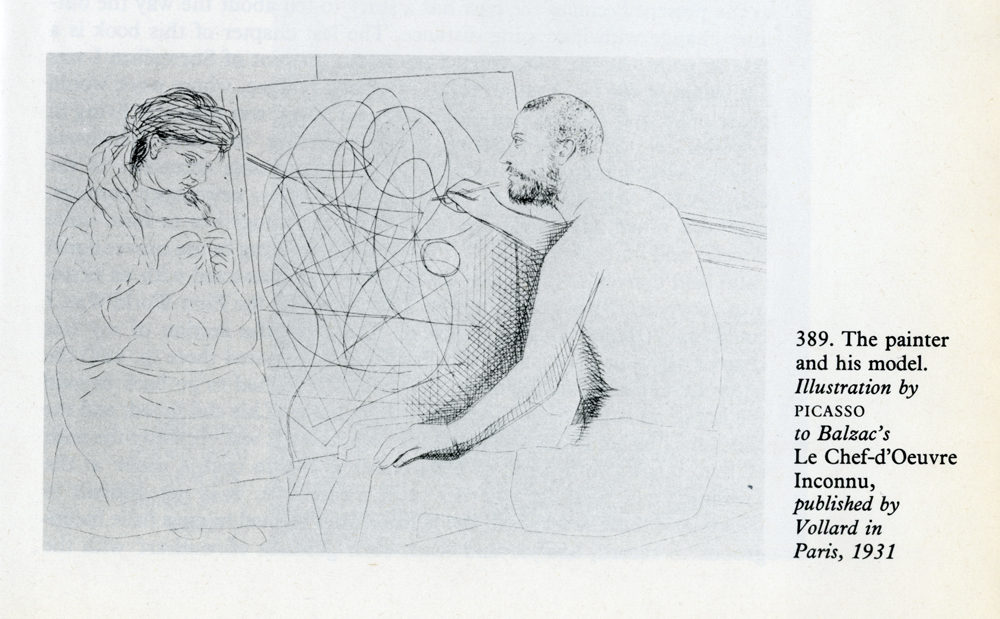

I would like to count myself among the ‘very astute’, but, alas, I was only astute enough to read the preface and would not have otherwise noticed the missing pictures. Far from announcing a defect, Schlagman’s note about the lacunae underscores a parallel story of art that Gombrich chose to tell with illustrations alone, almost as a series of visual footnotes to the written narrative. In his first preface from 1950, Gombrich explains their presence and purpose: ‘As a tailpiece to each chapter, I have chosen a characteristic representation of the artist’s life and world from the period concerned. These pictures form an independent little series illustrating the changing social position of the artist and his public. Even where their artistic merit is not very high, these pictorial documents may help us to build up, in our minds, a concrete picture of the surroundings in which the art of the past sprang to life.’

Looking through an older edition, I must say that the tailpieces tell a great story on their own while anticipating sociological studies that would be written by later art historians. The majority of the pictures – muted, apart from a caption – show artisans and artists at work, alone or with others. There’s a busy Greek sculptor’s workshop, including a foundry, depicted on an antique bowl; a Florentine print from 1465 shows a pair painting frescos on a building façade; painters study foreshortening, as depicted in an Albrecht Dürer woodcut from 1525. There are even parties, like the one taking place in an artists’ pub in 17th-century Rome.

The only sour note comes in the opening chapter on prehistoric and primitive art: a black and white photograph shows an Australian aborigine drawing on a rock, suggesting that native peoples do not live in the present. Throughout, there’s not much of an audience, apart from a few kings inspecting works in progress. More people – a public for art – start to appear only in the early 18th century: connoisseurs, followed by royal patrons, academy members and then Salon visitors.

Why did Gombrich leave the tailpieces out of his text? A master storyteller for both adults and children, Gombrich wouldn’t have lacked the skills to integrate yet another thread into his narrative. A clue seems to lie in his insistence that the tailpieces could help us ‘build up, in our minds, a concrete picture’ of the historical surroundings behind the production of art. Readers could not be told the origin of art in each period but had to imagine its emergence in their minds with the aid of pictures – much as children who cannot yet read must rely on pictures to understand a fairy tale. Indeed, a tailpiece is not only the end of a story but also a decorative design at the close of a chapter – the kind one finds in illuminated manuscripts and children’s books. While Gombrich wrote the book with teenagers in mind, his tailpieces stoked the imagination and transported all readers, whatever their age, to a more inventive mode of reading while reminding us that art books are essentially picture books for adults.

With this approach, Gombrich liberated images from the tutelage of the text. His tailpieces are not illustrations but a prototype for the photo-essay. He also comes close to novelists like Leonid Tsypkin and W.G. Sebald, who used images in an oblique, evocative manner. As cinema proved, and jpeg-laden blogs have confirmed, an image alone can drive a narrative. Ultimately, the moral of the story of art may well be that images say more when they speak for themselves.