The Bellwether Biennial

The evolution of the Whitney Biennial, an American institution

The evolution of the Whitney Biennial, an American institution

The 2017 edition opening weeks after the dawning of the new Trump era of American politics, the significance of the Whitney Biennial as a barometer of America’s culture may be more than ever. Founded in 1931 by the artist Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney as a grass roots initiative to support and show her fellow American artists, the museum flagship’s exhibition refused to adhere to the conservative, hierarchical exhibiting rules of the contemporary academy, instead presenting new work, by young artists, in an open, un-juried selection of work chosen by the artists themselves. The three curators responsible for the first Whitney Annual in 1932 (it would only become a Biennial in 1973) were themselves artists, and two of them went on to become the directors of the museum. This early grounding of its identity in the figure of the artist has been critical in shaping the Whitney’s continual re- assessment of what constitutes American art; Vanderbilt Whitney’s artist-centric, risk-taking approach has remained at the core of both the museum’s mission and the Biennial’s.

The willingness to take a chance on untested artists and ideas has allowed the exhibition to respond to the moment, year after year. Over time, the Biennial’s status as a recurring event has embedded that “rapid response” sensibility in the museum’s DNA as well. As such, the exhibition has a unique place in the pantheon of Biennials: a bellwether of the museum’s own internal evolution as well as that of the American artistic climate.

After the Second World War, then young Jackson Pollock’s debut in the 1946 Biennial, one devoted to primarily abstract work, was a key signal of this ability to rapidly respond to shifts in American modernism. When the art market began to gather strength at the beginning of the 1980s, the Biennial took on a more thematic structure and the museum’s curatorial staff began to work on some editions with outside curators. Loose themes like figuration, painting, or the East Village brought new young artists such as Jeff Koons, Julian Schnabel, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Christopher Wool into the Whitney’s fold. A film and video program, conceived to reflect the larger themes of each edition, continued to build a parallel momentum.

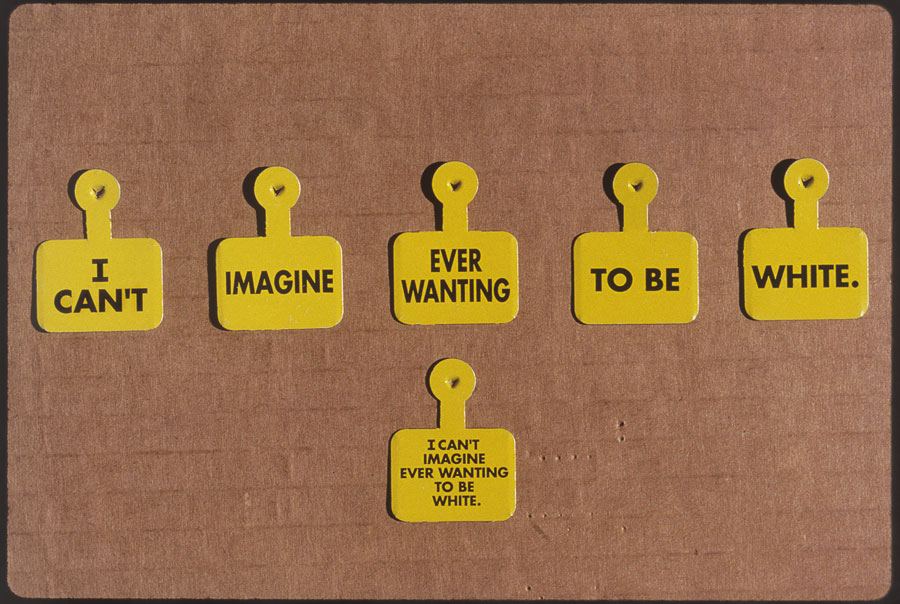

By the start of the 1990s, the pressing problems facing America following the end of the Reagan presidency coincided with a new polemical emphasis in curatorial practice worldwide. Acutely felt by the artistic community in New York, these issues were addressed rst in the 1991 and then the 1993 Biennials. In its attempt to confront poverty, racism, sexual identity, AIDS, the Gulf War and police violence, as well as e orts to include more women and more racial diversity, the 1993 Biennial in particular acted as a lightning rod for critics. By riling the old guard, the Biennial pointed to a new, more critical curatorial practice, in which the strongly argued positions and ideas of individual curators play an increasingly important role.

While the Biennial has rarely followed a formula – the 2006 one included nearly 300 artists, for example, while the 2008 and 2010 editions each included fewer than half that – as each subsequent Biennial progressed, timeliness has been a constant. The events of the day – whether September 11th, the Iraq War, Guantanamo Bay, Hurricane Katrina, the global economic crisis or Occupy – and related thinking about queer voices, racism, digital technologies, the internet and collectivity, have all in turn been mapped onto editions of the Whitney Biennial, directly or indirectly. In the 2006 Biennial, for example, during the height of the Iraq War, artists Mark di Suvero and Rirkrit Tiravanija re-constructed the 1967 Peace Tower created by artists in Los Angeles to protest the Vietnam War, with over a hundred invited artists contributing specially made panels. But relevance doesn’t always mean direct political commentary. Equally strikingly, for the 2012 Biennial, the entire fourth oor of the museum was turned into a space for a series of changing programs of dance, music and performance, foregrounding live, inter-disciplinary work within the museum for the first time.

Because the relationship between the Biennial and its host institution has long been symbiotic, these developments leave a permanent legacy in the Whitney. In order to support artists at the start of their careers, and to represent developments in American art at the moment they occur, the Museum has since the Biennial’s inception purchased works from each edition for its permanent collection. This commitment to young artists and new ideas enhances the Biennial as a platform, but also means that the museum’s collection today bene ts not only from early career works by significant artists, but work in dance, lm, expanded cinema and sound, which are less present in comparable institutions’ holdings.

The 2017 Biennial, curated by Whitney curator Christopher Y. Lew and independent curator Mia Locks, is the first in the Whitney’s new building, and the largest to date, occupying not only two full exhibition oors, but also the fifth floor terrace, the John R. Eckel, Jr. Foundation Gallery and the Hess Family Theater. The first Biennial in twenty years to open around the time of an election, the exhibition reflects the uncertainty of the turbulent current moment; the racially diverse group of 2017’s participating artists, of which nearly half are women, in their practices address urgent questions about personal identity, collaboration, immigration, place, and the impact of economics on both the institution and on artists.

Thinking back to its earliest days, it was two years after first Whitney Annual, in 1934, that Vanderbilt Whitney and Juliana Force (the museum’s first Director), organized the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. By presenting a group of recent acquisitions from the Whitney’s newly established permanent collection, they asserted young American artists’ place in an international dialogue – at the very same moment that nationalist forces elsewhere in the globe were moving in the opposite direction. At the beginning of a new, uncertain era of American history, the 2017 Biennial offers the chance to make another statement about what, and who, America is, and where it stands in the world.