Die 80er & "Geniale Dilletanten"

Städelmuseum & Haus der Kunst

Städelmuseum & Haus der Kunst

As the pre-1989 era seems to recede behind a curtain, an Iron Curtain even, two recent exhibitions have brought the period back into view. The 80s. Figurative Painting in West Germany at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum was devoted exclusively to works on canvas, while ‘Geniale Dilletanten’ (Brilliant Dilletantes) – Subculture in Germany in the 1980s at Haus der Kunst focused on the underground music scene, supplemented by selected artworks. Together, they created a picture and milieu study of a battlefield over which grass has long since grown, now a stomping ground for veterans telling how it ‘really’ was. But what was it like really?

The Städel show, curated by Martin Engler, director of the museum’s contemporary art collection, included around 90 works by 22 male and 5 female painters (a better gender balance than was usually achieved in group shows at the time, when Baselitz’s recent claim that ‘women don’t paint so well’ would have blended inconspicuously into the pervasive testosterone-fuelled prattle). For someone (like me) who wasn’t there at the time (too young, too uninformed, or both), entering the show felt like walking into a party, and the brash entrée was followed by various further high points. This is not a comment on the quality of all the work on show: the exhibition certainly had its share of mediocre work. And of rubbish. But it’s not often that one has the chance to see such a broad range of competing currents, live and in colour, including obscurities and failures (the last opportunity was in 2003 with Obsessive Malerei at Museum für Neue Kunst in Karlsruhe, with a smaller number of artists, all men). This made it possible to understand both those who were enthusiastic at the time (Rainald Goetz about Albert Oehlen!) and those who were profoundly annoyed (Benjamin Buchloh about everyone!), faced with painting that either ‘spontaneously’ celebrated the moment, or formulated a quick-witted response to the moment – while trying to join the poker game of art market hype using bluff and derision.

The brash opening was a room full of portraits. In Werner Büttner’s Selbstbildnis im Kino onanierend (Self-portrait masturbating at the cinema, 1980), the artist shows himself in crude, washed-out grey tones with an imbecilic stare, his mouth half open, sitting in a cinema seat, his pastel-pink member half concealed in a yellow popcorn bag, the index and middle fingers of his right hand tentatively holding its tip. The myth of spontaneous painterly intensity, with all its eroticism and heroism, is expertly deflated here by the awkwardness and embarrassment of an ‘adult’ cinema. The linking of eroticism and heroism is also behind Luciano Castelli’s Berlin Nite (1979) – this time as queer celebration. He and his shaved-headed friend, the artist Salomé, pose as twin satyrs whose pale torsos and heads, rendered with classic expressive strokes, glowing proudly in white and pink, surrounded by a smoky backdrop of spray-painted lines and brushstrokes in black. In Walter Dahn’s Selbst doppelt (Self twice, 1982), on the other hand, the head is duplicated as two rectangular boxes with triangular noses and tired eyes, both cleaved from the top by a hastily scribbled axe, alongside a vertical slogan in yellow letters: ‘Löscht mit Blut das brennende Wissen’ (Extinguish burning knowledge with blood).

Three main currents are already emerging here. First, Büttner and the ‘Hetzler Boys’ (the scene centred on gallerist Max Hetzler), primarily Albert Oehlen and Martin Kippenberger, who constantly picked at the scabs of painterly self-assertion in West Germany’s post-war bourgeois milieu, both ridiculing it and redrawing it for their own use. By contrast, as part of the scene centred on the artist-run Galerie am Moritzplatz in Berlin, Castelli und Salomé displayed and celebrated a transgressive homosexual lifestyle that was still very much taboo at the time, even in art. Dahn, on the other hand, as part of the ‘Mülheimer Freiheit’ group (named after the address of their Cologne studio) developed a kind of ‘Pop Brut’ combining iconic simplification with exuberant use of slogans.

These three lines – quick-witted mockery, self-assertion, simplistic pop – ran through the exhibition, both the hits and the misses. And they didn’t always match the lines dividing the milieus that competed for prestige, then as now, mainly between and within the cities of Hamburg, Cologne, Düsseldorf and Berlin. As Walter Grasskamp writes in the catalogue, a certain ‘historiographical confusion’ still reigns even today ‘because seemingly authentic accounts of what happened are mixed with local legends and partisan reports.’ Correspondingly, many of the period’s key protagonists are still reluctant to be ‘framed’ within specific historical contexts. But such geographical and historical categories are constructs that help to outline precisely such tensions. In any case, with hindsight it is clear that Kippenberger had the best sense of humour, that Oehlen later became a far better painter, and that Helmut Middendorf’s and Elvira Bach’s celebrations of cool nightlife characters in fast, garish strokes still look like murals for a then-trendy neon café. In his work, Salomé, however, goes beyond such mere self-celebration, with a sense of radical openness including the possibility of precarious self-harming. In a joint work painted with Castelli entitled KaDeWe (1981), the life-size bodies of the two artists hang on hooks like half pigs at the Berlin luxury department store of the title. The political dimension here is the way the grotesqueness of society is performed with the artist’s own body. The same applies to Bettina Semmer’s Kuh (Cow, 1983) in which a female Minotaur with a naïve look in its eye holds Eve’s apple in its hand, side by side with an exact copy of itself; this doubling reveals misogyny (linking of cow and Eve motif) as a reproduction of the cliché. Another great painting is Semmer’s Olympia (Deutsche Katastrophen Serie) (1985), based on a photograph of one of the terrorists involved in the attack on the Israeli Olympic team in Munich in 1972. The face with its stocking mask and dark skull-like eyeholes is framed by brutalist concrete balconies, and overlaid with semi-transparent patches of pale brown paint.

Apart from Semmer, Andreas Schulze is among the artists in this exhibition whose works have best stood the test of time – as in Ohne Titel (Wachtelbild) (Untitled, Quail Picture, 1983), whose quails, peas and blades of grass, spread across the large-format canvas like lost playthings, make it extremely hard to keep a straight face. In this show, Schulze’s intelligently absurd ‘naiveté’ also proved superior to the demonstrative naiveté of Milan Kunc, who indulged in a kind of late-Picasso, children’s book Pop. Nevertheless, seeing all this work together made it possible to define such preferences for oneself, rather than merely adhering to a preestablished canon.

All of this made clear that what the painters of the early 1980s were trying to set themselves apart from was not (as is often claimed) the supposed hegemony of 1970s academic conceptualism (after all, most of these painters thought conceptually and had undergone academic training). Instead, they were opposed to the discourse of neo-avant-gardist exclusivity that had also been rife within painting (as when, in the early 1970s, Philip Guston was rejected as a traitor for turning to cartoonish figuration); they were thus rebelling against the ideologically cemented purism of genres and styles viewed as mutually exclusive. As in almost any oedipally structured rebellion, however, this purism was repeated in altered form – this time via the policing of milieu borders on the basis of pedigree, and thus actually constituting a regression. But this is easily said today: how, if not via urban milieus setting themselves apart in a regressive, adolescent manner, would it have been possible to generate the necessary energy in the becalmed times of the Cold War, before the ‘multi-polar’ post-1989 world and the advent of digital networking?

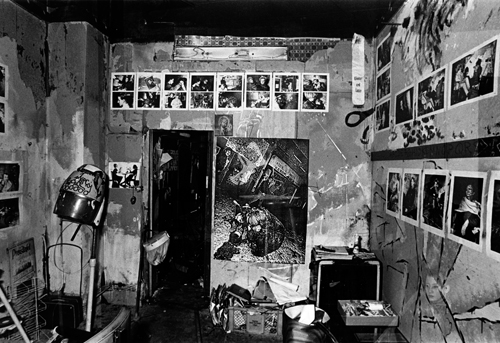

The show at Haus der Kunst showed the other side of the 1980s myth in the form of a selection of key underground bands: Einstürzende Neubauten, D.A.F., Der Plan, Die Tödliche Doris, F.S.K., Palais Schaumburg and Ornament & Verbrechen. (Why not Malaria? An important band, and one consisting entirely of women, who otherwise featured here only as individual members of F.S.K. and Tödliche Doris.) Whereas music was largely omitted in Frankfurt (thankfully, as it is so often used as a crutch to portrait the painters of the period – as if everything could be explained simply in terms of punk and its DIY ethos), the Munich show placed music centre stage. Presented on a large wall each, including pictures and a screen with film material, the selected bands formed the basis for this exhibition organized by the Goethe Institute and curated by Leonard Emmerling and Mathilde Weh. Originally conceived as a media-based show without artworks or artefacts that travelled to cities including Minsk and Novosibirsk, the exhibition makes no secret of its didactic slant, along the lines of ‘letting the world know what was going on back then in West Germany’ (and, to a lesser extent, in East Berlin, thanks to the inclusion of Ornament & Verbrechen). At Haus der Kunst, it was supplemented by a small number of important exhibits, including Bernd Zimmer’s almost life-size rendering in emulsion on canvas of an S-Bahn train (1/10 Sekunde vor der Warschauer Brücke – Stadtbild 3/28, 1978) that once graced the side wall of the legendary Berlin club SO36, for a single night.

More than in Frankfurt, this exhibition acted as a milieu study, especially thanks to photographs which lent an idea of the demeanour and style-consciousness of those involved. Take, for example, Gabi Delgado of D.A.F. sweeping ecstatically across the stage, or the three members of Die Tödliche Doris (Nikolaus Utermöhlen, Käthe Kruse and Wolfgang Müller) grinningly draping themselves around a urinal for an autograph card portrait: Marcel Duchamp, nightlife and a humorous allusion to sexualized pissing – three birds with one stone. From today’s point of view, the activities of Die Tödliche Doris feel especially fresh and timely: as in Sesselgruppe Kleid (dreiteilig) (Chair Group, Dress, actually not made until 1991) in which crosses between a man’s shirt and a woman’s dress are draped over garden chairs, flowing into one another as a cheerful allegory of queerness. In a mischievous Facebook post, Wolfgang Müller (who at the time had been responsible for the deliberately misspelled title ‘Geniale Dilletanten’) recently asked whether this particular work might not deserve to be purchased by a public collection, like the important canvases by painters of the period. Which brings us to the prospect of being ‘co-opted’ by institutions: it always used to be the case that musicians tended to want to go anywhere but the museum (standing for established culture as a whole) – and that artists tended to want access to the museum nevertheless. Ultimately, both have now ended up there. The effect is mixed: in some cases, it signals long-overdue recognition, in others it amounts to a kind of mummification. And that is a fair price to pay for each person who can now no longer ignore or play down the significance of figures like Bettina Semmer or Wolfgang Müller.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell