Dealing In History I

An essay by Brigitte Kölle on the crucial but overlooked role of Konrad Fischer and other Rhineland and Benelux gallerists who brought Conceptual art to Europe

An essay by Brigitte Kölle on the crucial but overlooked role of Konrad Fischer and other Rhineland and Benelux gallerists who brought Conceptual art to Europe

‘Dusseldorf is a city without a history that is constantly in need of a new face, a new history, to update itself. Which is why so much gets done here, and why the Dusseldorf scene is so open.’1 This is how Swiss artist André Thomkins described the situation in the capital of the German federal state of North-Rhine Westphalia, where he lived and taught in the 1970s. In the postwar period, the city’s openness, liberalism and tolerance drew many artists from across the country. Dusseldorf’s art academy soon became Germany’s most progressive: around 1960, the staff included Ewald Mataré, Bruno Goller, Georg Meistermann, Gerhard Hoehme, K.O. Götz and, from the summer of 1961, Joseph Beuys, who had studied there himself from 1947 to 1951, and the pull it exerted should not be underestimated. Nor should the special economic situation in the ‘Golden West’, one of the key industrial areas during the ‘Economic Miracle’. This situation fostered both the emergence of a caste of well-heeled, well-informed art collectors in the Rhineland, and the creation of a dense network of cultural institutions (museums, galleries, kunstvereins) that is distinctive and unique to this day.

The art scene of the late 1950s, ’60s and ’70s was marked by an increased demand for networking and exchange driven by the postwar need for information. New artistic networks grew up across national borders. At first, during the 1950s, Paris was the most important point of reference for artists in the Rhineland. This orientation was so strong that Dusseldorf was sometimes called ‘Little Paris’. More than anyone else, it was the highly educated Jewish translator and man of letters Jean-Pierre Wilhelm (1912–68) who, through Galerie 22, which he co-founded with Manfred de la Motte in 1957, familiarized people with the work and ideas of important artists and intellectuals he had met during his time in France and Spain: Wols, Jean Dubuffet, Antoni Tàpies, Pierre Soulages, Hans Hartung, Jean Fautrier. He also translated Spanish and French literature by Guillaume Apollinaire, André Breton and others into German, and introduced the poet Paul Celan to Dusseldorf.

During the 1950s, Wilhelm became an important conduit between French and German cultures, between Paris and Dusseldorf. He introduced the Rhineland not only to the French purveyors of Informel, but also to the American artists Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly, who he presented in the last show at Galerie 22 in May 1960. On his initiative, Henry Moore also visited Dusseldorf. The ‘New Music’ crowd, from the WDR Studio for Electronic Music in Cologne, were regulars at the gallery where, in September 1958, John Cage presented Music Walk, a work for one or more pianos, radios, whistles and water vessels. In addition, Wilhelm also brought happenings to Dusseldorf and organized the NEO DADA in Music concert featuring Nam June Paik on 16 June 1962 at the Düsseldorfer Kammerspiele. His activity as a trans-genre, trans-national communicator played a major role in invigorating the Rhineland art scene of the late 1950s and early ’60s.

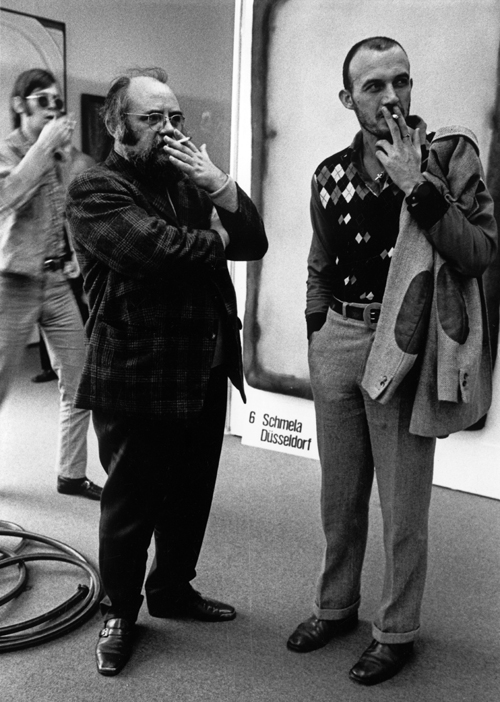

Just four weeks after the opening of Galerie 22, another influential Dusseldorf gallery started business at Hunsrückenstrase 16-18, Galerie Schmela. Its founder and director Alfred Schmela (1918–80) was a well-known Dusseldorf character, a temperamental man who liked to deliver his concise, unerring judgements on art in a local dialect. In his first, tiny gallery space in Dusseldorf’s old town, Schmela made history: in May 1957, during the opening exhibition of monochrome pictures by the then unknown 29-year-old Yves Klein, insults were written on the gallery window and the critical response ranged from bafflement to rejection. There followed debuts by Dusseldorf-based ZERO artists (Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, Günther Uecker), as well as the first European solo shows by the American artists Sam Francis, Robert Indiana, Gordon Matta-Clark, Robert Morris, Kenneth Noland, George Segal and Richard Tuttle. Schmela’s infallible feel for good art, his ‘nose’ – referred to by some as his ‘trunk’ – finally led him to Joseph Beuys, whose first solo show he presented in 1965. In the decades that followed, Beuys was to become Dusseldorf’s most important and most disputed artist. His teaching at the academy and his international reputation rubbed off on the city to no small extent.

Although Wilhelm and Schmela could not have been more different in terms of character, temperament and rhetorical skills, with their feel for art and their talent for creating cross-border networks they each performed a great service to contemporary art around 1960: Wilhelm represented strong links to western Europe, especially Paris, while Schmela focused on American art and experimental exhibition formats.

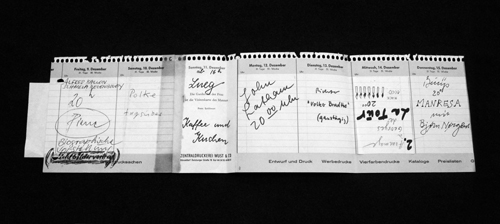

In 1967, ten years after the founding of Galerie 22 and Galerie Schmela, Konrad Fischer (1939–96) opened a small exhibition space in the immediate vicinity of the academy and the artists’ bar Creamcheese designed by Uecker, Lutz Mommartz and Ferdinand Kriwet. The space was in fact a passage for cars from the street to a back courtyard, but Fischer installed French windows at either end, creating a simple, functional space for art. Prior to this, Fischer had been an artist himself. He studied with Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke and Manfred Kuttner at the Dusseldorf Art Academy and had several successful exhibitions. Under the name Konrad Lueg, he had his first solo show at Galerie Schmela in July 1964. And it was Schmela who later recognized and fostered the young Fischer’s talent as a gallerist. Like the inaugural Yves Klein show at Galerie Schmela, the first exhibition at Ausstellungen bei Konrad Fischer (‘exhibitions at Konrad Fischer’s’: he always avoided the term ‘gallery’) was programmatic: in October 1967, Carl Andre presented his floor sculpture 5 × 20 Altstadt Rectangle made of 100 steel tiles, over which baffled visitors walked while searching the empty gallery walls for the art.

Andre came over from New York specially for the show in 1967. Inviting artists to come and make new works in situ (rather than having the finished work transported to the gallery) was a totally new approach – and one which, in spite of its apparent simplicity, would have notable consequences. On the one hand, it encouraged and enabled a type of art that responds sensitively and specifically to the site where it is to be presented, and on the other the presence of the artist created opportunities for exchange and networking with the local art scene. Since the cheapest transatlantic flight at the time called for a minimum stay of three weeks, there was plenty of time for the visiting artist to produce additional works, to travel, to visit exhibitions, and to mix with fellow artists, curators and collectors. For the international artists shown by Fischer at his legendary space in Dusseldorf, Belgium and Holland in particular became popular destinations for excursions. The Amsterdam-based artist Jan Dibbets remembers: ‘[…] Many artists travelled on to Amsterdam from Dusseldorf to to visit museums. Especially the Stedelijk Museum under Edy de Wilde, who started collecting Minimal and Conceptual art at the time’.2

More generally, there was much interaction at the time with artists based in the Benelux countries (Dibbets, Stanley Brouwn, Lawrence Weiner, Marcel Broodthaers) and with Belgian and Dutch collectors who were enthusiastic about the emerging Minimal and Conceptual art, especially Martin and Mia Visser from Bergeijk in the Netherlands, Herman and Nicole Daled from Brussels, and Anton and Annick Herbert from Ghent. Friendly contacts were established with like-minded galleries like Art & Project in Amsterdam and above all with Anny de Deckers and Bernd Lohaus’s Wide White Space in Antwerp. And because they represented some of the same artists, Fischer and de Decker (joined in certain cases by Heiner Friedrich from Munich) would sometimes share artists’ travel costs or the production costs for works. As far as institutions were concerned, the nearby Kaiser Wilhelm Museum and Haus Lange in Krefeld and Städtisches Museum in Mönchengladbach were popular destinations. Their ambitious directors, Paul Wember and Johannes Cladders respectively, often presented the first museum shows of American or European avant-garde artists: Klein, Christo, Jean Tinguely and Richard Long all had their first solo museum shows in Krefeld, and Beuys, Andre, Bernd and Hilla Becher, and Hanne Darboven (as well as many others) had theirs in Mönchengladbach.

The museums in Belgium and the Netherlands also excelled with major exhibitions at the end of the 1960s: in March 1968, Haags Gemeentemuseum opened the first big group show of Minimal Art with Andre, Ronald Bladen, Dan Flavin, Robert Grosvenor, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, Tony Smith, Robert Smithson and Michael Steiner. Under the title Minimal Art, the show toured in 1969 to Kunsthalle Dusseldorf and Akademie der Künste in Berlin. And on 15 March 1969, the group show Op Losse Schroeven: Situaties en Cryptostructuren (Square Pegs in Round Holes: Structures and Cryptostructures), curated by Wim Beeren, opened at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, before travelling to the Folkwang Museum in Essen under the title Verborgene Strukturen (Hidden Structures). A week later, the legendary exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, curated by Harald Szeemann, opened at Kunsthalle Bern with many of the same artists, later travelling to Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld and to the ICA in London. In an interview, Bruce Nauman (whose first European solo show in 1968 was at Fischer’s space, where he continued to show work regularly) remembered the lively exhibition scene at the time that offered young artists many options: ‘There were all those interesting curators in Europe that were doing all these group shows. So we all got a lot of exposure, more so than in the States. No one was doing this kind of stuff in the States.’3

Although he was a commercial dealer, Fischer also promoted and organized shows by avant-garde artists at public art institutions: in October 1969, he worked with Rolf Wedewer on the first major survey of Conceptual art, at Museum Schloss Morsbroich in Leverkusen, under the title Konzeption – Conception; in March 1972, working with Zdenek Felix, he organized the Konzeptkunst (Concept Art) show at Kunstmuseum Basel; and in 1972, together with Klaus Honnef, he curated a section of Szeemann’s documenta 5. A particular stir was generated by a loose series of exhibitions under the title Prospect at Kunsthalle Dusseldorf between 1968 and 1976 initiated and organized by Fischer and Hans Strelow with the stated aim of offering a ‘preview of the art in avant-garde galleries’. Each exhibition had a different focus, like the 1971 show dedicated exclusively to the media of photography, slides, film and video under the title Prospect 71 Projection (the first of its kind anywhere in the world) or the last show in the series, in 1976, which tried, under the title Prospect /Retrospect: Europa 1946–1976, to present Europe’s galleries as pillars of the avant-garde by looking back at key European exhibitions from the past two decades.

The Prospect series was interesting not only because of its avant-garde credentials and its unconventional, shifting focus, but also because of its position between the art market and institutional activities. With its clearly international profile (Prospect 68 featured 16 galleries from eight countries, including just one from Germany) Prospect must be understood as a response to Cologne’s Kunstmarkt, founded in 1967. It was not until 1971 that this fair organized by the ‘Society of Progressive German Art Dealers’ allowed non-German galleries to participate, as a way of protecting the German market from unwanted foreign competition for the attention of German collectors. At the same time, the subtitle given to the Prospect series – ‘an international preview of the art in avant-garde galleries’ – expressed the stated aims of presenting avant-garde art movements in an exhibition situation, of bringing international art to Dusseldorf, and of showing German art in an international context. These had also been the basic ideas that led to the founding of Ausstellungen bei Konrad Fischer. Unmistakably and irreversibly, the desire for exchange and international networking within a growing art world blazed a path for itself.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell

1 André Thomkins (undated), quoted from Helga Meister, Die Kunstszene Düsseldorf (Recklinghausen: Verlag Aurel Bongers, 1979), p. 7

2 From an interview with the author, in: Brigitte Kölle (ed.), okey dokey Konrad Fischer (Cologne: Walther König, 2007), p. 162

3 From an interview with the author, ibid., p. 187