Eau de Cologne

A round-up of five gallery shows in Cologne

A round-up of five gallery shows in Cologne

Dominikus Müller Painting, more than any other artistic medium, is talked about in a way that always has a touch of the flowery synaesthesic language fond to sommeliers and perfumers. This must derive from the medium’s high level of technical formality and the refinement that stems from its noble history. A bold red with notes of apricot; fine brushstrokes set against a roughly applied ground …

Kito Nedo The midnight-blue depths of the surface, the muddy blackness in the finish, and so on. You must be referring to the two gallery exhibitions in Cologne, concurrent with Art Cologne, that took up the theme of fragrance, explicitly and implicitly: Perfume, the group exhibition curated by Elena Brugnano at Jan Kaps, and When You Dance With The Devil, the Anna Virnich solo show at DREI. Both exhibitions operated within a field of ‘expanded’ painting that is minimalist-abstract yet sometimes murky.

DM That tension was precisely where Perfume positioned itself. In 91-A-2 (2014), Agnes Lux applied graphite and copper to numerous postcards and stuck them together into a geometric panel; Lydia Gifford placed two messily painted and tilted boards on the floor of the space (Furrow, 2013) and Amy Feldman emphasizes the frame with jauntily painted borders (Hello Tableau, 2013), bearing the work’s titled self-referentiality.

KN All of this conveyed an overall stylistic impression of understatement and wit – to continue with the fragrance metaphors, not wearing any terribly cloying perfume, thankfully. But Virnich went a step further. She ‘painted’ with patched-together pieces of lamb’s leather (Leather Oh Heather, 2014), treated silk with grease and patchouli (Untitled, #15, 2014) and sewed leaf-like fabric structures onto three elongated canvas objects for Traurige Tropen (2014).

DM Not a paintbrush was used. The viewer also saw a video showing burning potpourri. Also displayed in the exhibition was a petri dish with painterly smears left behind from the rising smoke. A perfume bottle rested on a small ledge. All that was really left of painting here was a scent trail, a ‘note’ of the medium. Paint and canvas were used only metaphorically, ‘belonging to the medium’ was only claimed through the format of the panel painting. This is, of course, only one – possibly the most contemporary – way of addressing painting as a medium: less ‘post-painterly’ and more ‘post-painting’.

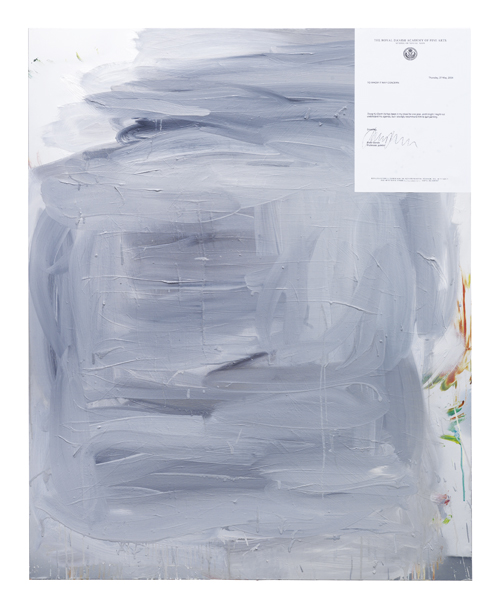

KN Fear of Reflection, Peter Bonde’s exhibition at Natalia Hug, was much more ‘painterly’ in the traditional sense – but, as the title indicates, it also revolved around the theme of self-reflection. Bonde used a surface of mirror foil then smeared paint on it in an impressively wild painterly style. The exhibition text spoke of ‘mudification’ – Lacan was just around the corner: the mirror stage, the ego-function. For this reason too, this work went beyond the question of painting to make a certain type of (social) reference. Rather than invoking other painters through a particular brushstroke or colour palette, he brought them into the picture through collages of catalogue pages or similar materials, some of them painted over.

100 × 80 cm, Natalia Hug

DM Stephan Jung’s show at Hammelehle and Ahrens offered a genuine contrast to the aforementioned exhibitions and their – however differently formulated – concerns with self-reflection. Rather than self-referentiality, this exhibition was about self-sufficiency. It shows a series of large canvases, each of them 3 × 2.6 metres (all Untitled, 2014), covered with colour grids, colour flows and spirals with photorealistic three-dimensional peaks in the middle. It was a confrontation with control and calculation, with painterly perfection and a peculiar form of emptying – very nearly sublime and conceptual in a classic sense – far ‘purer’ and more distinct than Bonde’s deliberate ‘mudification’ of the social and the formal, or the expansive tendencies of the first exhibitions we mentioned. In the strictest sense, this type of painting does not want to be anything other than painting. It spells itself out radically – that is, a thing solely of canvas and paint – rather than expanding into the great beyond of these parameters.

KN I was more impressed by the group exhibition in the same building, Unfinished Season at Nagel Draxler, curated by Marc LeBlanc. Whereas the Jung exhibition was a closed, even daunting, massif of paintings, at Nagel Draxler you could wander among the ruins of the genre. I particularly liked Amanda Ross-Ho’s oversized artist’s apron (Untitled Apron, 2011), an object that – quite convincingly – addressed the painter’s work in itself.

DM I wasn’t so sure about that apron. Of course, the humour of the work is nice, because it’s so deliberately banal – big apron, big hands; painting in a rough format – but the implied meaning that much and splatters on the artist’s apron is intrinsically painterly is too simplistic in my opinion. What I found more interesting in that exhibition – which included mostly young artists – alongside one of the current ‘masters’ of brushless painting, Stefan Müller – was the way the painterly was pushed towards the graphic in works by Julia Haller and Aaron Garber Maikovska. Garber Maikovska’s energetic black lines against a white ground seemed like sketches (e.g. Humphrey and Kids, 2014), while Haller drew scribbled lines that bound together the two canvases of a dingily gloomy diptych (Untitled, 2014). Drawing is, of course, an art form that plays a rather marginal role in contemporary painting’s drive for expansion.

KN Because drawing traditionally retains the flaws of the preliminary sketch?

DM Yes, if painting is the supreme discipline, then drawing is its humble Sancho Panza – as such it is somehow not capable of providing enough satisfaction to be an adequate counterpart for painting. Ultimately, this makes it quite charming.

Translated by Jane Yager