Get Weird: Justin Fitzpatrick, France-Lise McGurn, Issy Wood and Tom Worsfold

Surreal currents, charged objects and deformed bodies in the work of four emerging British painters

Surreal currents, charged objects and deformed bodies in the work of four emerging British painters

‘Mistrust in the fate of literature, mistrust in the fate of freedom, mistrust in the fate of European humanity.’1 Walter Benjamin’s description of the surrealists in 1929 holds pretty firmly in Britain in 2018. Of course, while each of the intervening 90 years has probably given grounds for some of the same distrust, if not despair, in this moment, every day brings new shocks, more disbelief, a deeper sense that ‘this cannot be real’.

The times, rather, are surreal and thus it feels fitting that the achievements and influence of the surrealists should be especially visible in the UK in the past year: in the reassessment of artists such as Penny Slinger (with the release of a new documentary, Out of the Shadows); in the Royal Academy of Art’s inspired ‘Dalí/Duchamp’ exhibition and in White Cube’s warmly received summer show, ‘Dreamers Awake’. The latter brought together surrealist works by 50 female artists – from historical figures such as Louise Bourgeois, Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning to their contemporary successors including Julie Curtiss, Tomoko Kashiki and Julia Phillips.

What follows is an attempt to chart this strange current through the work of four emerging British artists and see where it runs strong – as well as where it trickles.

‘I warn you, I refuse to be an object.’2

Leonora Carrington

At the private view of ‘Dreamers Awake’, the London-based artist Issy Wood overheard a man and a woman discussing her painting The Consultation (2017). ‘Can you look up Issy Wood’, one asked the other, ‘and find out when she died?’ It’s gratifying, Wood tells me, if someone can’t tell whether her paintings were made in 2010 or 1910. The untimeliness of these works is partly to do with their subdued palette and partly due to their downy, mottled, brushy textures, which recall the paintings of Gwen John and Walter Sickert. A rich softness is also achieved when the artist paints on velvet, as in Back at the V&A (2017): a technique that mingles the rich musk of old tapestry with the whiff of boot-sale kitsch. Yet, contemporary life is present, too: as in The Call (2017), acrylic nails and mobile phones abound in Wood’s paintings.

If something interests her, Wood tells me, she takes a photograph on her phone to use as source material for a painting. The mediated image, the object seen second-hand, is key to her approach: the many luxurious objects she depicts are mostly drawn from old auction catalogues, which Wood treats like textbooks of desire, manuals for mysterious constructions of want. It’s hard not to read the very fine silver tureen that occupies the almost-three-metre-long canvas Study for a Tureen (2017) – included in Wood’s recent Carlos/Ishikawa show, ‘When You I Feel’ (2017) – as a nod to the porcelain example found in Louise Lawler’s photograph Pollock and Tureen, Arranged by Mr and Mrs Burton Tremaine, Connecticut (1984). However, it turns out that Wood’s painting is based on a tureen owned by her grandmother: a woman, the artist says, ‘whose taste I hate but I want to take seriously’. The comment might well apply to another subject of Wood’s scrutiny, the late comedian Joan Rivers, who sold more than a billion dollars-worth of personally branded goods on the home shopping network QVC, funding both a lavish, gaudy lifestyle and no less extravagant plastic surgery. (Rivers’s deep, slanting eyes, like inset slabs of lapis lazuli, haunt the faces of many of Wood’s figures.) That Rivers dealt with personal loss (her husband committed suicide in his early 60s) is something inextricably linked in Wood’s studies, I think, to her accretion of glitz: as if embalming herself in wealth would protect Rivers against further assault. (After meeting the artist, I find a phrase isolated in my notes: ‘tragic luxury’.)

Melancholy is also present when Wood’s images are most overtly surreal (in the sense of the art-historical movement) – namely a loose series that she casually refers to as ‘objects-with-faces’, in which human features sprout on everyday objects: compacts, mirrors or, in the case of A Servant Who’s Not Serving (2016), a Menorah-ish candelabra. Yet, this strange half-life lingers in many of the things that Wood paints: look long enough at the oval indents that rim the Tureen and they, too, begin to resemble creeping fingertips or a row of clamping teeth. Meanwhile, is the closely cropped, chocolate-brown Untitled (Dog) (2017) a real creature frozen in movement or a canine carving? (It is, Wood tells me, also based on an ornament from her grandmother’s house.) Of all these things that seem to be alive, things-that-don’t-look-like-themselves, Wood reserves a particular fascination for the trompe-l’oeil clutch bags of Judith Leiber (like Rivers, a self-made, Jewish woman who survived great trauma), as depicted in Expensive Minaudière (2017), a curled, bejewelled feline clutch with an unnervingly human grin.

While these works recall the enchanted world of Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la bête (Beauty and the Beast, 1946) – in which wall sconces are held by living arms and ornamental figures flick their eyes around a room – the title of Wood’s 2016 picture is, in fact, taken from the 1991 Disney cartoon of the same story, in which an animate candlestick named Lumière laments: ‘Life is so unnerving / For a servant who’s not serving.’ For Wood, the lyric expresses the way inanimate things can seem to exercise an almost animistic aura, a draw, a needful pull – something not uncommon to the experience of addicts, for whom an idle bag, pipe or spoon sometimes simply begs to be used. In this way, for all the uncanny, disruptive, enchanted qualities of her work, I can see why Wood resists the ‘surrealist’ label for its associations with myth and fantasy; the things she paints come not from fairytale but from a fiercely personal place – they function less as productions of free imagination than as vessels for real, sometimes desperate states of psychic intensity. Tragic luxury, indeed.

‘I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.’3

Frida Kahlo

The idea that looking at something might be a different experience from looking at something you want animates the work of another former Royal Academy student, Tom Worsfold, who describes ‘seeing another man in the street and imagining his body sort of dissecting him’, as an origin point in his practice. There is something of the postmortem about Apparition (2016), the work which gave its title to Worsfold’s 2017 exhibition (also at Carlos/Ishikawa), in which three bodily extremities – a nose, an arm, a leg – jut from a tub of aspic-green liquid. The parts do not obviously belong together, while a plug-like form attached to a pink chain dangles to one side, surrounded by bloody splotches, suggesting a corpse being drained – or re-animated.

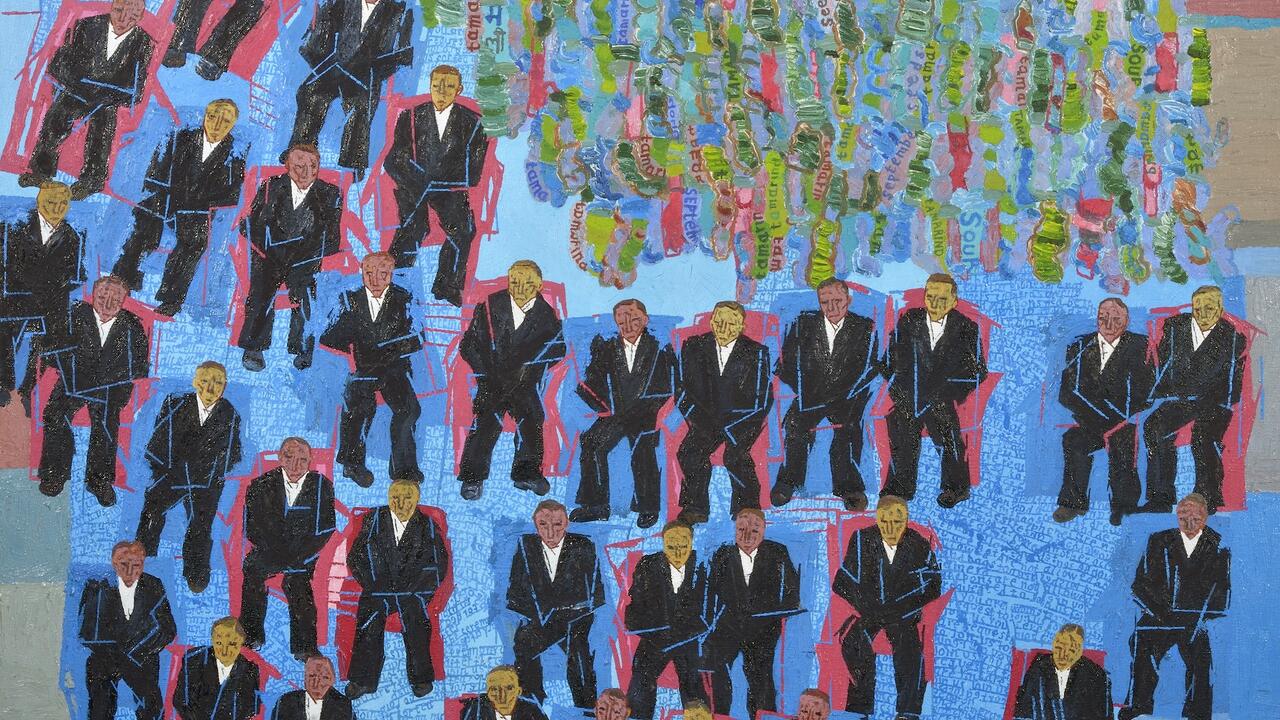

Worsfold’s recent pictures explore disarticulation in a less macabre and literal sense: though he describes the likes of Sink (2018) as ‘a body’, no figure is discernible. Instead, the elements in these pictures are knotted together like systems of organs – circuits of uncertain functions, actions or processes, slurping, grasping and sucking. The artist wants to see how far a picture can be disjointed and still hang together. A successful composition, he tells me, ‘has to wriggle around’.

This strangeness is achieved by Worsfold’s method of working on supports that are laid flat on a table (‘like an autopsy’, he says). He only stands back to take in a wall-mounted view when the major elements are in place. In this respect, I suggest, it’s a bit like the creation of an ‘exquisite corpse’, a method beloved by the author of the 1924 surrealist manifesto, André Breton. (I take the presence of a book by the psychoanalyst Carl Jung on Worsfold’s desk as confirmation of the hunch.) The results of this method bear comparison with the historical surrealists, too: the distended, inflated volumes of King (2018), for example, recalling Max Ernst’s Celebes (1921). However, even the most outlandish of the artist’s imaginings provoke a visceral reaction that is rooted in the reality of the body, albeit one displaced or substituted: witness the chain of sausage-like shapes that dangles aslant in Commuter (2017), a wonderfully creepy semi-invocation of the human figure. (A sausage, in one sense, is like a person: meat bunched up inside skin.)

The procession of ghoulish anatomies continues in ‘Felt Tip’ (2017), a series on sheets of A4 paper drawn in the titular medium, which Worsfold made for his show at Recent Activity in Birmingham. The bodies here are at once readable and rubbery, bendy and improbable. As if to underscore the sense of the figure as an elastic, endlessly deformable thing, in Football, Worsfold depicts a pair of grotesquely toned legs beside a collapsed football that is in the process of being inflated by a perversely narrow pump. Its rhythmic action is echoed across the series by other implied repetitive, manual movements – one swipes a thumb across a phone screen, another wipes the underside of an arm while washing, another squeezes a bottle of lotion between fingers. This is echoed by the artist’s application of pen on paper in countless masturbatory strokes, at once tender and mechanical. All of which suggests that our psychic lives consist, in part, of these repeated contacts with things – little everyday rituals of care and mania.

‘We are the sighs of the glass statue that raises itself on its elbow when man sleeps.’4

André Breton

That someone has not been taking care of himself is implied by the title of Justin Fitzpatrick’s Artist’s Proof: Kidney Failure (2018), part of his recent show, ‘Underworld’, at Vienna’s Kevin Space. No less elastic than Worsfold’s bodies, this figure – dressed in builder’s hard-hat and vest – sits catastrophically slumped over. That said, ‘his’ and ‘self’ are terms hard to delineate here: the tubular red and blue form over which the body folds, and which loops across the rim of the picture space, also seems to merge with the figure itself in the form of two veins that snake up the builder’s legs like vines. Twists and curls wind through Fitzpatrick’s paintings like curlicues, recalling art nouveau ornament, Celtic knot design and, perhaps most emphatically, medieval manuscript illumination. Fitzpatrick’s debut show at London’s Seventeen gallery in 2017 was entitled ‘F-R-O-N-T-I-S-P-I-E-C-E’. In Uranian Monks (2017), exhibited at Sultana in Paris, Fitzpatrick depicts two monks in hemp-coloured habits, one the inverse of the other, like figures on a playing card, joined by the rope belt of the Franciscan order and a glowing double-phallus: a dreamy manifestation of the kind of pent-up sexual energy that the late art historian Michael Camille attributed to life in a monastic community.5

In ‘Underworld’, the snaking curls were also manifested in three-dimensions in the form of floor-based sculptures: flesh-coloured worms with tiny capped heads that incorporated brooms or brushes and pans (Sodomy, 2018), like the unholy offspring of the dancing mops of the sorcerer’s apprentice from Disney’s Fantasia (1940) and the ‘chest-burster’ from Alien (1979). Apparently, the white balls that these creepy helpers sweep up are references to seminal fluid; this makes sense, as a kind of ejaculatory or hydraulic energy runs through Fitzpatrick’s images. Living things appear made of tubes, funnels, flumes – witness Cat Infected with Daisies and Medieval Hare Infected with Daisies (both 2017): their flat outer forms are run through with tendrils, sites of penetration and mutation. A text written by Fitzpatrick for the Seventeen show, ‘French Garden’, pushes the hydraulic imagination of the body to one extreme, with the artist articulating the different shapes that water takes in ornamental fountains (‘The Tulip / The Double Sheaf / The Centrepiece’) and then picturing himself a statue through which these waters flow. (‘I have water pumping out of my left breast, pinched between two fingers.’)

The ghost of La Belle et la bête’s romantic surrealism is once again abroad here – especially in the statue of Diana, which seems to spring to life in the castle garden to fire an arrow. But if this influence brings a rickety, premodern air to Fitzpatrick’s world, it is also punctuated by blatant contemporary props – internet search bars border the edges of some pictures and an elegant bird is startled by a bottle of Evian (Evian Goose, 2016). Where Sodomy abuts the wall, a pair of pristine football socks discreetly nestle.

‘The shapely one, the perfect one, so perfect that she doesn’t al-ways bother to take a head, arms or legs with her on her travels.’6

René Crevel

The dissolution of the human subject – it’s strange extension by Worsfold, its penetration by Fitzpatrick, its displacement onto the inanimate in Wood – is also rife in the work of France-Lise McGurn. The Glasgow-based artist’s installations, comprising wall paintings and studio works, are dense phantasmagoria of overlapping and interpenetrating people and parts. Faces, arms, eyes and fingers – rendered in slick, swift strokes in a limited palette – drift across space, intersecting each other. In one light, they resemble the postwar religious murals of – him again! – Cocteau but, then again, they also recall the hypnotically layered, graphic compositions of Francis Picabia’s 1930s figurative paintings, not to mention the breezy, casual, clean strokes of David Robilliard’s work in the 1980s. McGurn’s shifting amalgam of styles – like Wood’s or Fitzpatricks’s deliberate historical indeterminacy – results from a conscious interest in the look of things; a concern with how a brushstroke, a pose, the aspect of a face can be read as belonging to an era, as ‘period’. As McGurn once declared in an interview, the question is: ‘What is it exactly about an illustration of fashion that locates the image in Germany in the 1980s?’ Part of her answer was to collate a huge archive of found imagery: among the references listed on the page for ‘Archaos’, McGurn’s 2017 show at Alison Jacques Gallery in London, were photos of the 1960s singer France Gall, drawings by the director Sergei Eisenstein and stills from Brazilian sexploitation films known as pornochanchada.

‘Mondo Throb’, McGurn’s 2016 show at Bosse & Baum in London, drew its title from the 1962 ‘shockumentary’, Mondo cane (Tales of the Bizarre). A survey of ‘Rites, Rituals and Superstitions’ (as its American subtitle describes it), the film jumps across time and place, from Yves Klein’s body paintings to the beheading of bulls in Nepal. Channelling Mondo cane’s bold montage, the gallery was arrayed with splotches of pure colour, fragmentary canvases and wall paintings that sometimes spilled across them, arraying the space with a hallucinatory stew of figures, faces and stray limbs. The throb of the title could be read as a reference to a state of frenzy, the ecstasy of the club (McGurn runs a night in Glasgow, during which she sometimes makes paintings) or of the coven (the artist co-curated a show entitled ‘NEO-PAGAN BITCH-WITCH’ with Lucy Stein in 2015) – or to biological rhythms, the beating of the heart, the pumping of blood. In this way – like one of Worsfold’s organ-systems, but writ large across the room – the interiority of the body is invoked, as if the jumble of figures represented an inter-connected, deformed, centreless lifeform: a phenomenon gestured at by the title of the artist’s swooning 2017 mural in the stairwell of Tate St Ives, Collapsing New People.

I confess, part of me resists drawing these comparisons, arguing for trends, forging links: after all, concepts are flexible and porous; they can be bent to accommodate and exclude. Yet, sometimes, as Benjamin wrote: ‘Intellectual currents can generate a sufficient head of water for the critic to install his power station on them.’ However vague, I do see some current running through these artists’ diverse practices. Where it will run, and what form it will finally take, is another question. But then, these are strange times.

1 Walter Benjamin, ‘Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia’, 1929, reprinted in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms and Autobiographical Writings, ed. Peter Demetz, New York, 1978, p. 191

2 Leonora Carrington, quoted in ‘Dreamers Awake’, exhibition catalogue, White Cube, London, 2017, p. 32

3 Frida Kahlo, quoted in ‘Mexican Autobiography’, Time, April 1953, p. 92

4 André Breton, ‘Le Palais idéal du Facteur Cheval (Postman Cheval’s Ideal Palace)’, 1932, reprinted in Scanning the Century: The Penguin Book of the Twentieth Century in Poetry, ed. Peter Forbes, London, 1999, p. 51

5 Michael Camille, ‘Mouths and Meanings: Towards an Anti-Iconography of Medieval Art’, Iconography at the Crossroads, ed. Brendan Cassidy, Princeton, 1993, p. 43—57

6 René Crevel, ‘The Noble Mannequin Seeks and Finds Her Skin’, 1934, reprinted in The Surrealism Reader: An Anthology of Ideas, eds. Dawn Ades and Michael Richardson, London, 2015, p. 41

Main image: Tom Worsfold, Sink, 2018, (detail), acrylic on canvas, 1.4 × 1.2 m. Courtesy: the artist

Issy Wood lives in London, UK. In 2017, she had a solo exhibition at Carlos/Ishikawa, London, and was included in group exhibitions at White Cube, London, Independent Régence Brussels, Belgium, and Reading International, UK. Her work is currently on show in ‘Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired by her Writings’ at Tate St Ives, UK, which runs until 29 April.

Tom Worsfold lives in London. In 2017, he had solo exhibitions at Carlos/Ishikawa, London, and Recent Activity, Birmingham, UK.

Justin Fitzpatrick lives in London. Earlier this year, he had a solo show at Kevin Space, Vienna, Austria. Last year, he had solo shows at Seventeen, London, and Galerie Sultana, Paris, France, and his work was included in group shows at Musée Estrine, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France, The Sunday Painter, London, and Proyecto Medellín, Mexico City.

France-Lise McGurn lives in Glasgow, UK. In 2017, she had solo shows at Recent Activity, Birmingham, and Alison Jacques Gallery, London, and was included in a group exhibition at David Roberts Art Foundation, London. Her wall painting at Tate St Ives is on view until September.