Good Riddance

Accretion – the growth of several things into one, or the build-up of extraneous things – was the subtext of many curatorial endeavours from the 1990s on. The interest in networks, archives and storage – evidenced in the numerous exhibitions of collectors’ donations to museums, for instance – was driven, at least in part, by a need to explore and make known the manner in which those things were being amassed. It was not enough to have a vague sense of objects being gathered somewhere for some unspecified reason: we needed to know how they were being collected, where they were being held, who was amassing them and why.

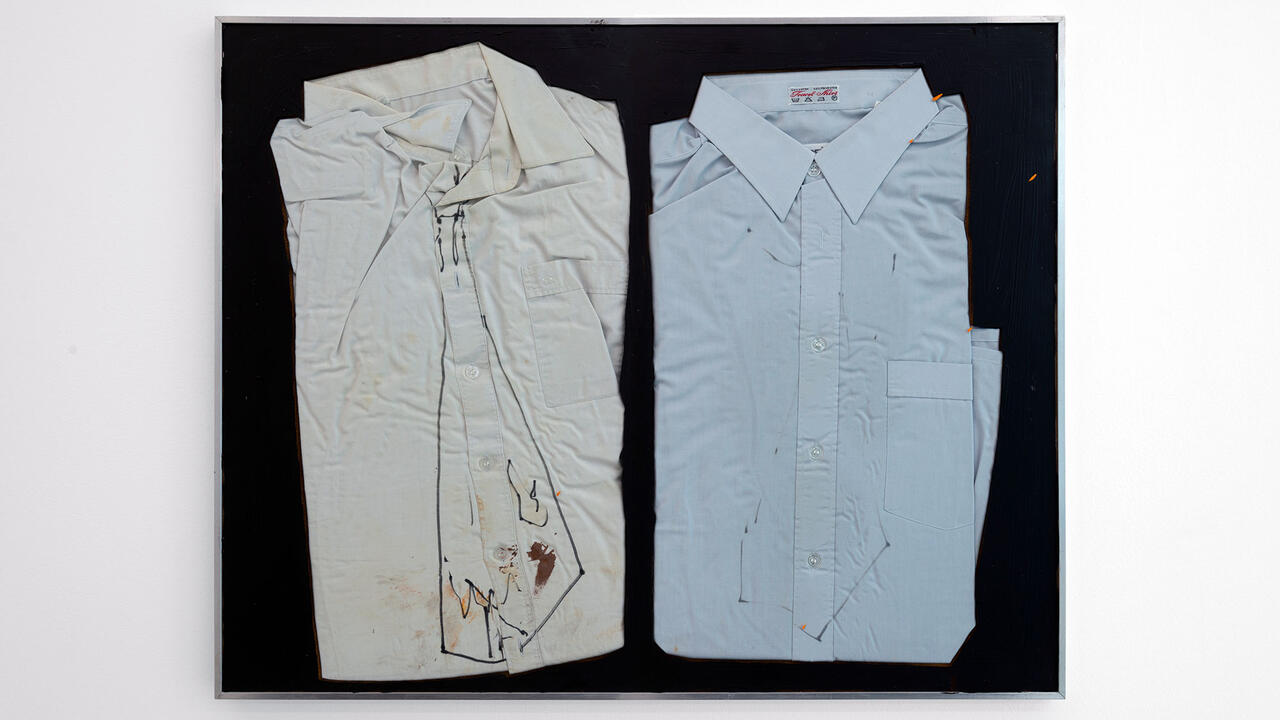

‘Good Riddance’, curated by artist Claire Davies and art historian Sam Gathercole, was a break from this line of thinking, seeking to undo the interest in building up by exploring the ‘potential of taking-away and getting-rid-of as a means of making’. Not an easy task for a show containing work by seven artists working in various media in MOT’s tiny space. However, they pulled it off by pairing known work, such as Lawrence Weiner’s

wall-mounted text REMOVALS HALFWAY BE-TWEEN THE EQUATOR AND THE NORTH POLE (1969), with less well-known pieces, such as Leo Fitzmaurice’s You Tell Me But You Never Listen (2007). If Weiner points back to the move from sculpture to the separation of the physical shape of words in the construction of language in Conceptual art, then Fitzmaurice shows that the pendulum does not have to swing back to Minimalism if form is exposed.

REMOVALS HALFWAY BETWEEN THE EQUATOR AND THE NORTH POLE glided in a diagonal midway across the central space of the gallery, looking down on Fitzmaurice’s box-like constructions. Made from consumer packages, which have been stripped of their logos to reveal white frames marked by abstract primary colours, You Tell Me But You Never Listen was arranged as a grouping on the gallery floor. The boxes resemble a small purpose-built village of generic Modernist models (think Alvar Aalto, Ernö Goldfinger or Philip Johnson). Weiner’s sprawling text was their town marker, like the iconic Levittown sign that once announced the suburban Utopia in New York. Fitzmaurice’s little forms are also biomorphic, positioned as though watching John Clayman’s slide show Empty Frames (2006), which was projected low onto the wall beneath the Weiner.

This juxtaposition solidified the curatorial claim of finding innovation in removal. Clayman’s slides are a collection of black and white photographs of iconic site-specific art works. Taken from books, the photographs were re-shot and manipulated to remove the original subject. This mirrors Weiner’s removal of the artist from his text works, which can be constructed by anyone according to his directions. Clayman’s slides include some of Weiner’s contemporaries, such as Gordon Matta-Clark, Walter de Maria or Ed Ruscha, but the artist has also been removed. The slide show feels a bit clinical, just as Weiner’s words often feel a bit nonsensical (half-way between the equator and the north pole would be an east–west no-place). However, the addition of Fitzmaurice’s forms as an audience revived the space between the projection and the wall – reducing, if not completely removing, the purpose of the viewer from this part of the exhibition. Removal as a concept could have been restaged as a parody on architecture, design, site-specificity, earthworks or Conceptual art.

The rest of the exhibition did not convey the same degree of friction. The collective Brown Sierra (Paddy Collins and Pia Gambardella) exhibited two well-crafted installations. The first, Field No. 2 (2007), was placed to the right of the front door. It is a floor-to-ceiling wall of disused speaker components attached to hanging wire. Disassembled and rendered silent, the components are, literally, rid of their original purpose. The installation is striking, although it would have benefited from more space. Reduced Mechanical Sound-Scapes (2007), a collection of music-box mechanisms, was placed on an adjoining wall. Removed from their containers and attached to the wall, they are tiny, unrecognizable metal contraptions whose sound could be activated singularly or in concert. Their sparse placement against the white wall added to the eerieness of their sound. Paul Davis’s digital animation Inside Edition (2006) and Jem Finer’s video Dusty Skies (2007) shared a space with Brown Sierra’s Field No. 2. Both Finer and Davis are recognized musicians; Finer was once a member of the Pogues, and Davis makes electronic music with the BEIGE Programming Ensemble. Finer’s video uses Bob Wills’ Country and Western classic Dusty Skies (1941). As dust falls on the LP playing on a turntable, the sound of the song becomes muffled to the point of inaudibility. Similarly, Davis removes the musical sounds of a Super Mario Brothers video cartridge by deleting its game code, which reduces its function to encoded data. The result is a moving pattern of bright and Pop-y pixels.

The curators are right to point out that ‘Good Riddance’ is ‘not indicative of an act of remembrance or nostalgia’, although they verge on disproving themselves a few times with their emphasis on the machinations of bygone technology (slides, video games and vinyl records). Perhaps, however, this was itself a meta-critique on removal.