Highlights 2014 – Ela Bittencourt

2014 was a great year for cinephiles. The one regret I have is not having seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Goodbye to Language (2014) in 3D, a film that is said to revolutionize cinema to the point where watching it in 2D, as I did, is pointless. Luckily, as far as 2D pleasures, there were plenty, starting with White Shadow (2013, 2014 release), a stunning debut by Noaz Deshe, so far scantily present on the festival circuit. Berlin and Los Angeles-based Deshe sets his film in Tanzania, inspired by real-life stories of Africa’s albinos, who are mercilessly hunted because their organs are believed to have healing powers. In the film, a young albino, Alias, escapes after his father’s ambush. Alias sells DVDs in a cutthroat city and finds companionship in a rural albino shelter, but is betrayed by his uncle. Deshe’s hallucinatory storytelling and edgy camerawork have a primal power, with a witchdoctor that channels Flannery O’Connor. Deshe stresses the sensory experience, and Alias’ plight is so agonizing, this is the one film whose vision and humanity continue to haunt me.

2014 was a great year for cinephiles. The one regret I have is not having seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Goodbye to Language (2014) in 3D, a film that is said to revolutionize cinema to the point where watching it in 2D, as I did, is pointless. Luckily, as far as 2D pleasures, there were plenty, starting with White Shadow (2013, 2014 release), a stunning debut by Noaz Deshe, so far scantily present on the festival circuit. Berlin and Los Angeles-based Deshe sets his film in Tanzania, inspired by real-life stories of Africa’s albinos, who are mercilessly hunted because their organs are believed to have healing powers. In the film, a young albino, Alias, escapes after his father’s ambush. Alias sells DVDs in a cutthroat city and finds companionship in a rural albino shelter, but is betrayed by his uncle. Deshe’s hallucinatory storytelling and edgy camerawork have a primal power, with a witchdoctor that channels Flannery O’Connor. Deshe stresses the sensory experience, and Alias’ plight is so agonizing, this is the one film whose vision and humanity continue to haunt me.

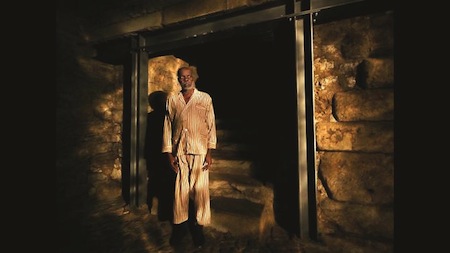

A number of masters made notable films last year, including Godard, but also Nuri Bilge Ceylan with the austerely sublime Winter Sleep (2014), Andrey Zvyagintsev with the flawed Leviathan (2014), and what was to be the final film from Alan Resnais (who died in March), with the mild but pleasurable Life of Riley (2014), to name a few. Yet some of the most imaginative features, I believe, have come from lesser-known directors. Among them, Ventos de Agosto (2014), by Brazil’s Gabriel Mascaro, displayed the similarly uncanny power as White Shadow, or as this year’s stunner, Horse Money (2014) from Portugal’s Pedro Costa. Both Costa and Mascaro explore lost, forgotten worlds: Costa in his dreamlike portrayal of Cape Verde immigrants, all being treated in a desolate hospital in the slums of Lisbon, where the dire present and the violent past overlap; Mascaro in his vivid portrayal of a Pernambucan coastal village, where the bones from a local cemetery wash up on the beach. Deshe, Costa and Mascaro employ nonactors, and their films evince wondrous energy at the fiction/nonfiction vertices.

Another example of such happy convergence is the steady ascendancy of the American indie filmmaker Nathan Silver. His latest film, Uncertain Terms (2014), features mostly professional actors, but its energies, beginning with the script that is based loosely on his mother’s experience as a teenage mom, Silver’s casting of her and of himself in the film (Nathan and Cindy Silver also acted together in Silver’s feature debut Exit Elena), to Silver’s insatiable interest in characters’ inner lives over plot, all contribute to the film’s complex communal experience. To the extent that Silver’s films feel like happenings – which in no way denigrates his fine eye or his ear for dialogue – I like to think of Uncertain Terms as kin to recent nonfiction films, such as Robert Greene’s Actress (2014), Roberto Minervini’s Stop the Pounding Heart (2013), Andrew Droz Palermo and Tracy Droz Tragos’s Rich Hill (2014), or Niels van Koevorden and Sabine Lubbe Bakker’s Ne Me Quitte Pas (2013), all powerfully affecting hybrids that collectively redefine the word ‘performance.’

On the brilliant unclassifiable end, 2014 American audiences were finally introduced to the work of the British filmmaker, Joanna Hogg. Three of Hogg’s films, Undecided (2008), Archipelago (2010) and Exhibition (2013), all previously featured in The New York Film Festival, were given a theatrical run. Hogg also likes to work with nonactors, as she did casting a local cook and her own painting teacher in the masterful, minor-key family drama, Archipelago, in which fragile allegiances are built and raptured; or by casting singer Viv Albertine and artist Liam Gillick in Exhibition, about a childless middle-aged couple who must part with their beloved home/architectural wonder. Hogg’s visual precision is architectonic, for who can forget the eerie light that permeates the house in Archipelago, the island’s landscape amidst which the film is set, or the porous inner/outer quality of the brutalist modern house in Exhibition? Hogg grows more audacious with each film, and Exhibition plunges into subliminal realms, expanding the notion of realism.

2014 was also an important year for documentaries. Frederick Wiseman’s National Gallery is an opus on institutional bureaucracy, but, amidst the chatter – of curators, restorers, educators and administrators – somehow also proves that art is inexhaustible. In a climate of diverging opinions on the purpose of documentaries, from activism to the primacy of the image, Wiseman fits no trends. With Laura Poitras’s CITIZENFOUR (2014) sailing confidently through the award season, and a new Joshua Oppenheimer doc on the horizon, the next year should spark further debates. Meanwhile, documentaries such as Jeff Reichert and Farihah Zaman’s Remote Area Medical (2014), a devastating portrait of what decades of America’s haphazard healthcare policies and winner-take-all economy have wrought, keep prodding our collective conscience.