Home Away from Home

Novelist and artist Douglas Coupland’s pop-modern second residence in West Vancouver

Novelist and artist Douglas Coupland’s pop-modern second residence in West Vancouver

There’s something about Seaton House that immediately makes you feel as though you’ve been transported into some other time that isn’t necessarily the past or the future but a zingy confection of both. Maybe it’s the whiteness of the exterior walls that evokes achromatic aspirations of Utopias of yesteryear. Or perhaps it’s the idyllic wildness of this suburban setting, replete with skipping squirrels, punkish Steller’s Jays (the mohawked local birds), and a black bear that rummages through rubbish bins for leftover pizza. Actually this is someone else’s life – or, more precisely, the pop, picturesque second life of Canadian novelist and artist Douglas Coupland and his partner, the architect David Weir.

Together they’ve fashioned mid-20th-century Seaton House into a home that is as playful with references as it is liveable – for in the history of North American domesticity, comfort has always had an ideological imperative. It runs right through La-Z-Boy armchairs and refrigerators bearing crushed ice on tap. When European Modernism made its way to Vancouver via the Technicolor dreams of Los Angeles’ Case Study Houses, all that angular austerity was gladly abandoned. In its place, 1950s consumer-driven expression took hold. Huge picture windows turned the insides of houses into product-proud vitrines while the car-port territorialized the sacred love of the automobile – that enabling device for suburban sprawl and weekend getaways.

Funnily enough, Seaton House offers Coupland and Weir a getaway not from the distant, frenzied madness of a metropolis, but – all of 30 seconds walk away – from their main house. In order to appreciate the Apollonian poise of Seaton House (carefully ordered, light-filled, sober), it helps to picture the Dionysian interiors of this other home (cave-like, jumbled, materially dense), which is located through a gap in the fence at the bottom of the garden. ‘It’s like the inside of my brain: all organic evolution,’ Coupland says of the 1960 home designed by Ron Thom that the couple have lived in for 14 years and call ‘Craigend’. Shrouded by thick vegetation, its dark-chocolate timber exterior is carefully concealed, but it is TARDIS-like on the inside: a series of lightly terraced spaces that cluster around a Japanese-style water garden. Every surface of Craigend seems to support a plethora of accumulated, orchestrated things: Canadiana, scale-models, 1950s building kits, brightly coloured plastic shapes and masses of Coupland’s prints, collages and sculptures. When Seaton House came on the market last year, Coupland and Weir saw an opportunity to add to what was missing in their intensely lived in and private residence: a ‘public’ satellite space where friends and guests could be entertained and stay, as well as a semi-permanent display of many of Coupland’s art works from the past decade.

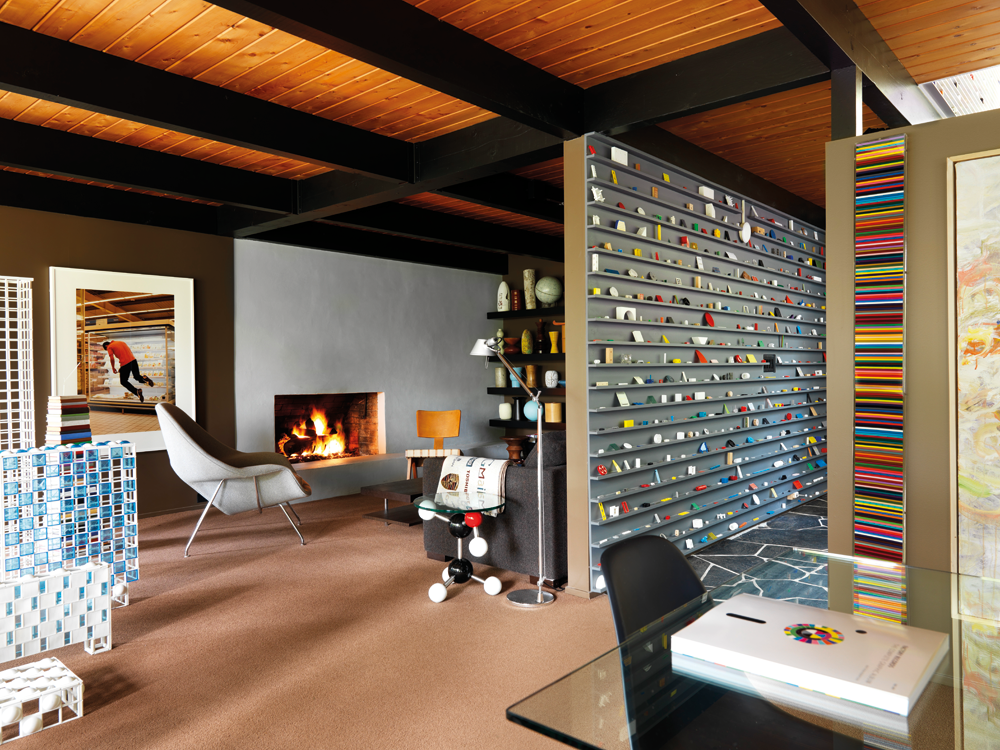

Since local developer and architect Duncan McNab built Seaton House in 1958, subsequent owners had ‘unloved’ it, according to Weir. ‘At first we thought there were animals in the house but then we realized it was the old radiators clanging.’ Restoration meant gutting the interior completely while leaving intact the cedar ceiling on the ground floor and a hidden flagstone floor by the entrance. The building’s overall proportions are low and wide, a quality common to other houses built by McNab on the same road, which spread out over conspicuously large, rolling plots. As you pull into the car-port, you see, on the first floor, a large replica (made by Coupland in 2001) of the Twin Towers; it’s both a monument to that fateful day and a straightforward homage to architect Minoru Yamasaki’s laconic serial forms. Strung up on the front of the house, dangling by the main entrance, is an inverted stack of primary-coloured maritime buoys, a symbolic ripple from Vancouver’s sea-trading history. Close by, a native goose pecks away at the soil. It doesn’t move from its spot. I wonder if it’s less scared than I am of the roaming bear. Inside, a hefty wrestler in a photograph by Brian Howell (Asian Cougar, 2002) seems to be jumping onto one of Coupland’s sculptures, (Downy Fabric Softener, 2000), a person-sized detergent bottle minus its garish labelling. To the right is an installation, Brick Wall (2008) also by Coupland, which he says is ‘the raison d’être of Seaton House’. It used to be in his studio at Craigend and a larger version of it is housed at the Canadian Center for Architecture in Montreal.

Seaton House’s iteration comprises an entire matt-grey wall laden with 20 miniature shelves, each three centimetres deep. A meticulous matrix of tiny coloured pieces (provenance: Lego sets, Star Wars toys, unknown) are distributed over the X and Y axes, a flattened picture plane of isolated fragments. This formal technique is repeated through the house several times, with hundreds of regimented dice in the stairwell, scores of eccentrically shaped ceramic vases in the living room, Chinese pill bottles in the ground floor bathroom and characterful drinks bottles in the corridor. Coupland told me that arranging colours and forms on purely compositional rules provides him with a necessary non-verbal escape from the tyranny of words. This is a writer who thinks images.

Prior to his 1991 debut novel, Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, Coupland had spent the 1980s studying sculpture at Vancouver’s Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design. A self-described autodidactic writer, he attributes Andy Warhol’s Diaries (1991) and Jenny Holzer’s ‘Truisms’ (1977–ongoing) as entry points into what language could do, and still feels ‘more at home in the art world than the literary world’. Perhaps the one conventional writerly trait shared by both houses is a palpable sense of retreat and repose. The view through Seaton House’s rear windows, beyond the darkly stained decking, reveals a garden enclosed by the kind of tall trees I associate with the forests that appear in Coupland’s most apocalyptic novel, Girlfriend in a Coma (1997). The rear door to the kitchen opens in halves, like a stable door, as though Mr Ed, the talking horse, might pop round for a natter while food is being prepared. After all, Mr Ed was owned by an architect and for the most part would only converse with klutzy human, Wilbur Post. Two more geese keep guard – as motionless as the one I saw upon arriving. These plastic props were used by Coupland in a 2004 show at Canada House, London, titled ‘Canada House’. (Geese figure heavily in his Canadiana myths.) The rest of the ground floor is taken up mainly by an L-shaped open-plan living and dining room. By the stark, switch-operated fireplace is a picture of a man floating in a supermarket – from the series ‘Hyper’ (2007) – spectral goings-on by the cheese section courtesy not of David Blaine but of French photographer Denis Darzacq.

While most of Seaton House is finished in a palette of umbers, caramels, greys and maple wood, the biggest space, at the top of the stairs, is all white-on-white, and operates most frequently as a gallery – though occasionally Coupland and Weir undertake special projects here. The eerie Twin Towers take up the central position and, next to them, a similarly scaled though completely blanched replica of Toronto’s CN Tower and another of Coupland’s blow-up sculptures: mutant toy soldiers the size of The Incredible Hulk entitled Gorgon (2004). Close by, a biomorphic white Charles and Ray Eames chaise-longue is ontologically paired with a hard-edged black leather Ludwig Mies van der Rohe chaise-longue in the opposing corner. A painting by William Betts (I-10 and McRae, November 12, 2006 10:09 am, El Paso, Texas, 2008) shows a CCTV image of a motorway in coarse, machine-rendered pixels. A large wall piece by Coupland (Luxury Factory, 2007) comprises a grid of cotton spools that spill their spindly thread onto the floor, somewhere between Damien Hirst and Eva Hesse. All are invocations of industrial progress: mass-produced excellence, television towers, traffic jams. The 20th century. In the master bedroom a triptych by Jeremy Green (Man in Black, Man from La Mancha, Man Who Sold the World, 2008) summons the spirits of Johnny Cash, Clint Eastwood and Ziggy Stardust – but as if they were all starring in Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream (1893).

Throughout the house, these juxta-positions and affinities multiply: between Coupland’s collagey, assemblagey, appropriation-happy work and the art work of other artists set against familiar furniture classics. Weir’s witty architectural attentiveness often works directly with these visual set pieces and as such the boundary between object and setting falls away. Regardless of how close their two houses are, it proved impossible to live part-time in one and part-time in the other as they had first imagined (apparently you spend most of your time collecting things you need from the house you are not in).

During last year’s exceptionally snowy winter, Weir and Coupland moved into Seaton House for two months to see how the new environment might affect them. It was an experiment that required self-imposed and serendipitous rules. Coupland broke his ankle in Seaton’s back garden and was forced to convalesce there without constant access to Craigend. Whereas it is his ritual to start writing new books in hotel rooms (often in Hawaii), Coupland began his biography on Canadian media guru Marshall McLuhan immobile in Seaton House (reclining is, apparently, the best position for creative writing). He finished the book in Craigend when they both moved back in Spring 2009. I’m not sure if McLuhan ever used the double meaning of the word ‘model’ in The Medium is the Massage (1967), but it’s what comes most strongly to my mind about this project. On the one hand, the formal clarity and period detailing of Seaton House is like a scaled-up version of one of Coupland’s favoured building kits from the 1950s, and is full of other things that have been scaled up and scaled down, a sort of Matrushka doll of models. But there’s a second meaning to the word ‘model’: that of an ideal or fantasy, as in ‘a model democracy’.

In Coupland and Weir’s personal cosmology, Seaton House started out as a ‘model’ house that manifested what they thought was missing in their domestic lives. Since then, it’s grown into something else. Like life, and the unfinished white column of Lego bricks Coupland has encased one of the house’s columns in, it’s always in progress. Many of us dream about doing the same thing – fantasizing about the environment we’d make if we could reinvent ourselves completely. For my part, I’d keep everything at Seaton House as it is. But I might spare the bear’s impromptu guest appearances.