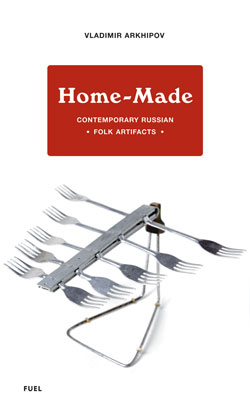

Home-Made: Contemporary Russian Folk Artifacts

The failure of perestroika is complex. Some may argue that Mikhail Gorbachev’s economic reform at least led Russia’s 15 republics on the road to full-scale change, but Russian sociologist and satirist Alexander Zinovyev’s coining of the phrase catastroika pretty much sums up what most Russians thought of glasnost in the late 1980s (he also pointed out that the word perestroyka in Greek means ‘accident’).

One of the predominant features of the perestroika era, of course, was shortage. Of everything. Where Soviet citizens were accustomed to not having appliances, computers or televisions, suddenly on the eve of being Russian citizens they were also going without food, clothing, soap and other basic necessities, making already difficult lives more challenging and dehumanizing. But it is often said that innovation is born of necessity, and there may be no better document of the phenomenon of the handmade everyday object in its pre- (and post-) perestroika manifestation than Home-Made.

Since 1994 engineer/physician/artist Vladimir Arkhipov has been ‘acquiring’ objects for his ever-expanding travelling exhibition the ‘Museum of the Handmade Object’ (some iterations have been called ‘Post-Folk Archive’). He wanders Russia’s centres and hinterlands, seeking out the hand-made – and the makers – in a valiant attempt to celebrate the unrecognized designer, artisan and inventor. Home-Made gathers objects from over 50 years that represent individuality triumphing over the mainstream, disposable culture rampant today. The creators of each of the 200 or so objects in the book are given voice too. Printed below each photograph of every object is a small portrait of the maker and an explanation of how and why he or she opted for the hand-made over the shop-bought.

Some of the objects are generated by thrift (‘Why should I go traipsing round the shops looking for a new colander when I can still use this one?’ and pull-tabs from drinks cans altered to replace phone tokens); some from need (a shuttlecock so meticulously crafted from a plastic bottle as to appear laser-cut; a torch powered by a Polaroid camera battery found on a rubbish tip); others from creative impulse (a ‘basket’ crafted from a deflated, striped rubber ball); some from sheer will (a complicated two-barrelled mousetrap from scrap metal and springs; a dog muzzle crafted from a lovely, worn piece of leather from a woman’s shoe). Others are an inventor’s fancy: a magnetic funnel. (‘What can I tell you? … I read in a magazine that magnetized water is good for you.’) Tellingly, the number of television aerials in the collection (seven, including one made with forks and another with bicycle wheels) outnumbers the number of shovels (four).

There are objects of beauty in the book too: a bronze bath plug made from a plastic mould; a set of rosary beads made during a prison stay; a toy battleship; one of the aforementioned aerials (made from the base of a lamp and a piece of laminated fibreglass) looks like a piece of Dutch Modernism; and a lampshade made from a piece of lace and an old straw hat that looks like something out of next season’s range at Habitat.

The utilitarian objects people make for themselves reveal not only the routine of daily life and culture but a real feel for design and an upholding of the traditional importance of craftsmanship and – they’re not unusual in this, are they? – a desire for beautiful, functional things.