Bruce Hainley and Jordan Stein on Time, Tides and Jay DeFeo

Hainley speaks to Stein about his new book, Rip Tales, a homage to DeFeo and San Francisco

Hainley speaks to Stein about his new book, Rip Tales, a homage to DeFeo and San Francisco

Bruce Hainley: Your new book, Rip Tales: Jay DeFeo's Estocada & Other Pieces (2021), is an ode to San Francisco and its artists, but it’s also about the conversations that people who are committed to art have and that become how so much art is remembered once it is no longer visible – whether in dark alert behind a wall, like DeFeo’s The Rose (1958-66), or even more secret, as the career of April Dawn Alison. Although George Kuchar is one of the dedicatees of Rip Tales, you decided not to have him or his work literally in the book itself. I wonder if you could talk about that decision as a way of discussing what you set out to do, with this elusive DeFeo work at its heart rather than something else, say Kuchar’s Secrets of the Shadow World (1989-99), a title that would serve many works by the artists you love and discuss.

Jordan Stein: I suspected that a good way to approach ideas of multiplicity might be to orbit the irretrievable; absence contains so much. The DeFeo work was destroyed before it was finished or photographed, so it was a valuable starting point. As a curator, artworks are often at the centre of my life, but art is about so much more than artworks, and has something to do with impossibility. I knew that Rip Tales wasn’t an exhibition, so I was able to think about time, space and visibility in a much different way, and transform the idea of a centre.

I’m glad you asked about George. While Rip Tales begins with a story about moving to San Francisco and studying with Trisha Donnelly, I actually took his class first. I blush easily, so I wasn’t exactly prepared for the semester-long production of George’s Kiss of Frankenstein (2003), in which I played a leading role alongside Linda Martinez, his muse at the time.

I thought of something a number of times in the course of putting Rip Tales together, which is that the most effective way to see a star in the sky is by looking slightly askance. Not only can you perceive starlight more clearly that way, but it inspires a reconsideration of what it means to perceive, both hyper-literally and metaphorically. Maybe George is my San Francisco star, the most exciting artist I’ve ever known. When I think about what he ‘taught’ me or what I ‘learned’ during those weeks of overdubbing outrageous dialogue in a tiny bathroom on campus, my brain short-circuits. A chapter about him would have made the book go dark, or too bright.

I did, however, make a show about George’s dog, Bocko, in Chicago a few years ago. Bocko figured in a number of iconic works, so it was a way to think about George while looking away, in this case at another species.

BH: It tickled me that George was delighted to discover that I priced his astounding painting, Bocko (1970), when I had to, so high. I did so not only because George should always have been well paid but also because I didn’t want it to disappear from the world into the hands of a collector who didn’t know its true value – which, actually, should be tenderly akin to that of Van Gogh’s Portrait of the Artist’s Mother (1888).

The value of the destroyed, absent, private, off-piste, overlooked, impossible – these might all be proxies for the inestimable – is something you probe. Could you say something about how you reckon with value(s) in terms of the various hats you wear?

JS: You were justified in pricing that painting as high as you did; it should go to a museum or have its own museum. As a writer curating a show at a commercial gallery, you had a kind of permission to do that – something simultaneously preposterous and legitimate; maybe that has something to do with value, real value.

Forgive me for quoting Emily Dickinson, but she suggests that we ‘Tell all the truth, but tell it slant.’ I think that value, like truth, is at perpetual risk of going straight. The art market is a fiction, but it’s anything but slant, and the same goes for followers, viewers or customers. Consensus isn’t slant and it can be really damaging to art, and to vision.

As an independent curator – and one mainly working in public institutions – sales has never been a rubric of success, and I’ve relied on teaching and miscellaneous projects to finance Cushion Works, the exhibition space I operate in San Francisco. But the pandemic has scrambled all that, and now I’m sort of an accidental dealer on top of everything else, which is both exciting and confusing.

BH: Rip tides: this oceanic force haunts your title of Rip Tales. One crucial current (material?) you dwell on and manifest in the book’s form is duration, time going by – most immediately in your tracking of DeFeo’s various returns over years to the unfinished painting Estocada, its remains, but also in syncopating the chapters ‘about’ DeFeo with other (related) figures: the decades that April Dawn Alison worked away figuring herself out; the life cycle of Bruce Conner's Homage to Jay DeFeo (1959). How did you think about time in putting the book together as well as in your choice of artists and works?

JS: Time and tide, right – the Bay Area as a series of coastlines (edges), and time itself as a material or medium, an endless pull. The good, long story of DeFeo’s Estocada is interrupted a number of times by other stories and other voices. The artists I’m most interested in take their time not exclusively to ‘finish’ discrete works, but to surrender to something big, weird and possibly related to the oceanic force you mention.

BH: You’re not interested in solving something, despite your diligent gumshoeing. You provide tales, rooted in the compost of conversation, that can spark thinking, but the book, so effortlessly, by being structured around ‘interruptions’, puts a premium on silence, on what can’t be said, what’s conveyed when words aren’t needed. There is a politics to this decision, although it isn’t what’s often recognised as ‘political’ right now.

JS: As you can imagine, I spent a lot of time with DeFeo’s papers, artworks, interviews and more. And after all that, did I see her any more clearly? To an extent, of course, but can I tell you what truly motivated her as an artist? I found her just out of reach, which was revealing in its own way. I don’t think she sought definition, but instead a kind of generative instability. She couldn’t be solved for.

Art speaks in its own myriad ways and shouldn’t be called on to speak like we do. We forget that art exists in the first place because it can’t be said any other way. I sense an increasing defensiveness of art’s ‘aboutness’ by its professional-managerial class, which I find cynical, because, as you note, an artwork is capable of extraordinary and radical directness on its own terms. I love a ruthless artist – not an asshole artist, but a ruthless one. Ruthlessness can be sweet, admirable or heartbreaking in its vision and commitment.

So much of life is exactly what it seems – the cops are racist, capitalism crushes, it’s not looking good for planet Earth. But art isn’t what it seems. Given how screwy the world is right now, I can understand people’s discomfort with this idea, but I think we need at least one thing that we can’t see right through. And I think an artist has to protect herself, at all costs, really, from what anybody or anything wants from her. It may be wise to stay silent, slip between the cracks, and embrace a kind of politics that doesn’t look like politics.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 224 with the headline ‘Time and Tides’.

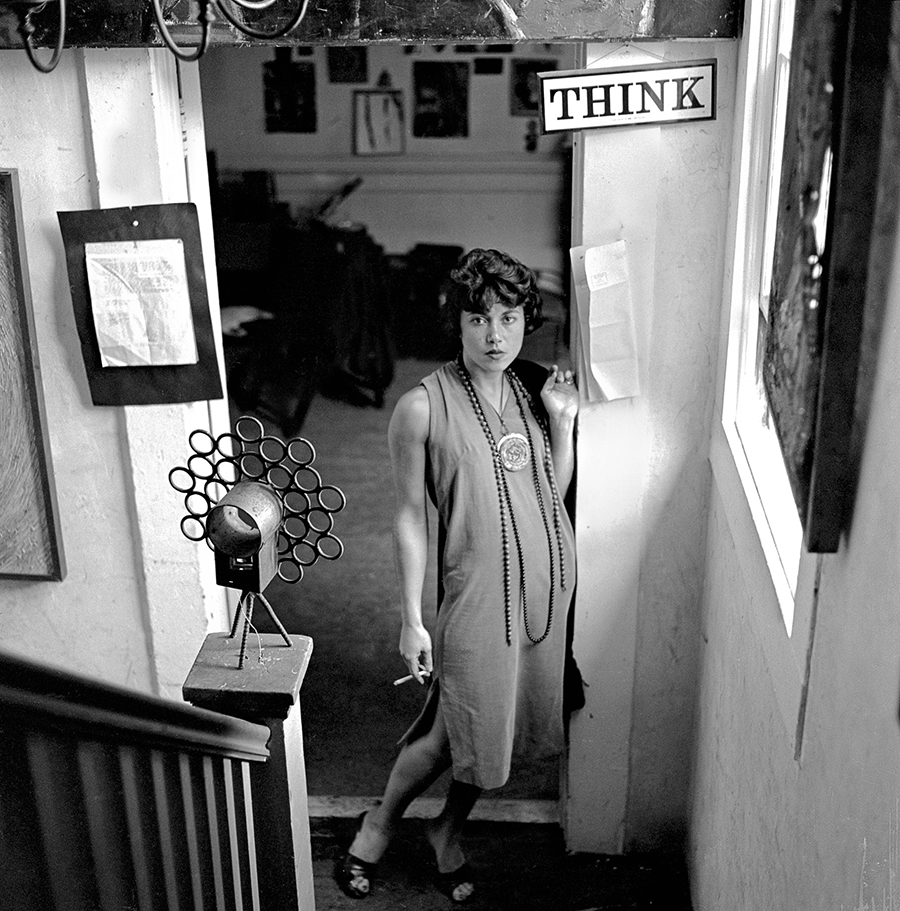

Main image: Bruce Conner, THE WHITE ROSE, 1967, film still. Courtesy: © Conner Family Trust