Laetitia Gendre

Galerie Thomas Fischer

Galerie Thomas Fischer

Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas lies before me in a display case. Or rather, what is left of the Mnemosyne Atlas after Laetitia Gendre has worked on it for The fake, the fold and the erased, her second solo exhibition at Galerie Thomas Fischer. Gendre has emptied out Warburg’s legendary panels with antiseptic precision: all that remains in The Erased (2014) are the white-on-white translucent outlines of the roughly 2000 pictures Warburg pinned on to wood panels covered with black cloth in the 1920s. An iconoclastic gesture or an homage to the father of visual history?

Warburg’s picture atlas remained fragmentary; he continued to rearrange it until his death in 1929. It is considered both one of his most obsessive and oft-cited undertakings. In a cosmos spanning Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1486) to female golfers, zodiac signs to advertising images, Warburg not only surpassed the limits of his discipline, art history, but also explored the continued existence of ancient gestures that persisted in images to his day. In his diary, Warburg described the Mnemosyne project as the ‘iconology of the interval’. When Gendre systematically erases the illustrations and displays the panels as a topographical structure, she appears to want to erect a monument to precisely this ghostly ‘interval’.

What initially comes across as cheeky iconoclasm, then, reveals itself as a reverential bow to and clever commentary on Warburg’s atlas. Paradoxically, however, without the visual power of Warburg’s reproductions, one is reminded of today’s sterile algorithms behind the Google Image search function. Fittingly, images of Gendre’s stripped panels flicker wildly in a PowerPoint-style projection next to the display case. The observation conveyed by this shift of medium – namely, that the computer-generated picture atlas of a search engine ultimately generates nothing more than empty shells and meaningless grids – is, however, a banal one. The Erased could have done without this shift to the digital and its apparent criticism of the arbitrariness of the Internet’s masses of images.

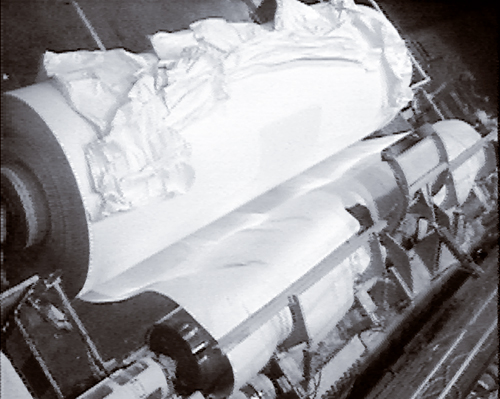

In the front room of the exhibition, by contrast, the viewer finds a downright plea for the poetry of pixels and digital images. In Wind on a reel (2013), we witness the imagery taken from the surveillance camera of a paper factory, resulting in what Warburg would call ‘pathos formulas’. Formulaic gestures of intense emotionality, which Warburg recognized above all in ‘accessories in motion’ such as waving hair and fluttering clothing, emerge on a production line in this video. We become slow-motion witnesses to the moment at which a gigantic paper roll entangles itself and slowly puffs up into sculptural shapes before splitting with expressive theatricality and bringing the machine to a halt. Gendre had piano music in the style of a silent film score composed as a soundtrack for this paper chaos. A comparison between the mechanically revolving paper roll and analogue film readily suggests itself. Rather than visual criticism of power politics – as seen, for example, in Harun Farocki’s appropriations of surveillance videos – Gendre stages a sort of medial comedy of mistaken identity, with surveillance footage, silent film score and sculpture facing off against one another in irritation.

Warburg remains the implicit vanishing point of all these manoeuvres. This is also true for Gendre’s collages of drawings on the adjacent walls (B Story I–V, 2014): ecstatically contorted bodies and expressively wide-open eyes quote images from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), B-horror movies and ancient sculptures. They are little short of didactic presentations of Warburg’s cosmos of ideas (e.g. breaking down boundaries between high and popular art, juxtapositions of historically disparate images). Imagery that is so thoroughly deleted in The Erased returns to the gallery walls in the form of exhaustively repeated quotations. The conceptual joke of the emptied Mnemosyne pages pales in the shadow of these collages of pathos. If Warburg could see this, perhaps he would snag one of Laetitia Gendre’s rubbers for himself.

Translated by Jane Yager