Lily van der Stokker

It's the little things that pile up: the used envelopes, unpaid bills, catalogues, bits of notepaper and the dust. A room is a trap for time. Clean it as much as you want, throw everything out at periodic intervals, but the place you inhabit cannot but become a depository of spent time.

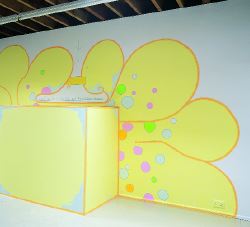

In Lily van der Stokker's art time takes on tangible form. It is with you in the room, a Technicolor, infantile cancer that bulges from the wall, spotty, lime green and shapeless. The wall drawing, a space-eating protrusion that she made in the long garage shed of the Cabinet Gallery, was accompanied by plans for madder, larger follies: Art by Older People, Extremely Experimental Art by Older People, forms that sprout, inflate and hang there on the wall, connected to sofas on which you can while away your time. Old couples, hand in hand, soldier on down the years. We are 68 and 67, reads the title of one design.

It 's a Dutch thing, of course, this obsession with interiors, and the time that passes quietly, even drearily, on a weekday morning as the servant scrubs the stoop and the little girl plays with a cat as a cloud passes by. Pieter de Hooch was an artist who depicted the passing of time in a nondescript way, painting a house by a canal, the courtyard of which was kept neat against the detritus that marks the approach of death. Where is the dust in a Vermeer room? Swept away fanatically from the field of vision. What the bourgeois Dutch seemed to dream of, as we do, is a room so stylish, sociable and well kept that time can never weigh you down: the perfect loft. Van der Stokker would come into such a perfect room, take a look at the big empty wall and propose a stupid, amorous mural: a sofa against the wall, clouds, flowers and wallpaper designs emanating from it, suspended over your head, the room full and cluttered. But as the pleasure of all this chaos begins to seduce you, it would all go wrong. Instead of assiduously recycling bottles, you would begin to let them pile up. Soon it would be as entropic as van der Stokker's phantasmagoric portrait Old Men in 1807 (2000). What is the precise melancholy of this picture? Blobby forms, cactuses without the spikes, Philip Guston heads without the cigars and stubble, all form a flaccid landscape that is decorative, even vacant. Yet the title suggests so much more; a moment in history, a fragment of time that has caught on your shoe and won't come off, art as regurgitated chewing gum. And art as furniture; shabby furniture that was new once, the saggy remnant of a utopian housing project grown old and plump.

Old Men in 1807; Delft in 1654. Out of the blue, the Dutch city was partly destroyed on October 12, 1654, when a gunpowder store exploded. There's a painting of the aftermath by Egbert van der Poel; the same flat, wide city we know from Vermeer's View of Delft (c. 1661) but with a void at its centre where every building has disappeared, and bodies lie among broken timbers. Imagine the stable, comfortable Dutch interiors of those paintings, the slow nondescript everyday moments, the maid pouring milk, the cavalier chatting to the mistress, the boy playing with the cat, the woman at the virginal. Then picture it all blown apart. Van der Stokker's monstrous transformation of the Dutch interior is finally comparable to Joan Miró's assault on Golden Age painting in Dutch Interior I and II (1928), in which the homely world of Jan Steen is turned upside down in a carnival of objects. Miró takes the orderly perspective of a Dutch room, with homely people conversing among solid, well-built items of furniture - a high-backed chair, a table with a damask cloth, a mullioned window - as an image of all ordering systems. His deformations of the Dutch interior anticipate van der Stokker's wall drawings. In Miró's interior, the objects that form a rational system of things, a consoling world, take leave of their moorings. They inflate, distend, grow eyes, curl and gallop in a space that is still a room, but it is transformed from a home into an asylum populated by phantasms. Van der Stokker's art just sits there, flops down, watches TV, flicks through a magazine. It acts young, but it knows it's getting old.