Manual Therapy

The musical pioneer Hans-Joachim Roedelius on his search for inner harmony

The musical pioneer Hans-Joachim Roedelius on his search for inner harmony

Dominikus Müller In early September, Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt will host a four-day festival dedicated to your life’s work. The festival is called Lifelines, and your own lifeline, as well as your path to music, ran anything but straight. Didn’t you first work as a physical therapist in the 1960s?

Hans-Joachim Roedelius Yes, I did. The war brought nights of bombing to my hometown of Berlin. The evacuation took me first to East Prussia and then to Sudetenland, and from there to Lower Lusatia during the exodus of Germans in the aftermath of the war. I fled East Germany in 1953 as a soldier forced into service with the National People’s Army. They didn’t catch me, but I still had to serve about two years in GDR prisons, including Bautzen, because I was stupid enough to believe GDR officials when they promised not to prosecute me if I returned voluntarily. After my early release in 1956, I was allowed to enroll in training: specializing in nursing, end-of-life care, and physical therapy. In 1960, completely out of the blue, I received a Stasi summons to show up for an interrogation, and that’s when I moved to West Berlin for good, one year before the Berlin Wall went up. But I was already part of artists’ circles in the East; I knew Helene Weigel and Eva-Maria Hagen, Nina Hagen’s mother, as well as many other East Berlin artists.

DM What kinds of things influenced you? What were the main triggers?

HJR One of my patients in West Berlin was a pianist. She introduced me to theatre and musical theatre and gradually introduced me to the art and cultural scenes in West Berlin. Also, between 1963 and 1968, I spent several months each summer in Corsica. I helped set up a nudist camp there, did roofing work, waited on tables, worked as a cook, an ice cream vendor, as a potato peeler, toilet cleaner, guide on expeditions into the mountains of Corsica and flight attendant, but later on I mostly gave massages. Finally, some French guests I met brought me back to Paris to work as a masseuse – they really valued my massage skills. I was seen as a kind of hippie healer, a long-haired, barefoot Rasputin. You have to imagine: I walked into the Élysée Palace literally barefoot! One of my clients at the time was the wife of the President of the French National Assembly. It was during this time that a friend introduced me to the music of Iannis Xenakis and Pierre Henri. Hence the idea to switch from the art of healing to the art of music.

DM When did you start making your own music?

HJR At the end of 1968, together with Conrad Schnitzler and Boris Schaak, I founded and helped run a club in Berlin, the Zodiac Free Arts Lab, which for a brief time was a meeting place for the city’s up-and-coming music community. It didn’t take long for Schnitzler to back out again, though, as he often did with the projects he helped initiate, such as Cluster, which we founded together with the now recently-deceased Dieter Moebius. Schnitzler also left Cluster, albeit after a longer period of time. The Zodiac didn’t last long, only about a year. We set off for Africa with Human Being, our music project after Schnitzler abandoned the Zodiac project. When we arrived in Casablanca, we all contracted some type of dysentery, and then we split up. After that, I went back to Corsica with my girlfriend, where I knew I could earn a little money giving massages.

DM So the massage work carried on in the background the entire time?

HJR Yes, I had to earn money somehow. This only really changed when Moebius and I settled in Forst im Weserbergland in 1972. We were invited to live at this former tithe house with a group of friends and artists to work on a friend’s very ambitious project. In order to survive, we had to do arduous manual activities that were ultimately extremely beneficial to us: planting a garden, laying pipes, connecting a toilet. We had to set up a situation for ourselves but lacked the requisite funds. At some point, Michael Rother joined us and we founded Harmonia. Later Brian Eno grew curious about what we were doing and came to play with us. Cluster carried on the entire time, I launched my solo career, and that’s how it all started. An unbelievable number of things happened in the seven years we lived there.

DM You’ve been labeled a ‘pioneer of electronic music’, although for a long time now, many of your solo releases have been far more influenced by classical piano – specifically, a very elegiac manner of piano playing. What can the piano do that the synthesizer can’t?

HJR We still don’t know exactly what electronic sound material actually does to the body, or how the body reacts to an electronically generated frequency. Does the body ‘naturally’ take in every kind of sound? We didn’t start off with the aim of doing something new. We wanted to create our own sound-language. It was all a process of trial and error. At first, of course, it was all a very specific kind of racket, a noise actionism, the type you might call ‘industrial’ today, and it sometimes sounded unbelievably jarring and loud. I have permanent hearing loss from it. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the longer Moebius and I were at it, the more we realized that we had a certain obligation to ourselves and to others. Our path was preordained: away from urban civilization and towards rural civilization. And from that point on, of course, something had to change in the music, too. You can hear this in Zuckerzeit (Sugartime, 1974) and Sowiesoso (In any any case, 1976). It’s not that we deliberately wanted to make electronic music more harmonious, but our new living situation automatically took care of that, both in terms of content and form. We started to compose friendlier music, and this went for playing live, too.

DM I recently read this nice sentence on your Facebook page: ‘People may say I am one of the inventors of soundscapes, but I always wanted melody.’ What do you think is so special about melodious soundscapes?

HJR It’s what happens when you make a sound on a piano, let it fade away a bit, and then add a second one. I grew extremely interested in the interferences that arise here, because when you pay attention while you’re playing, music happens alongside the deliberately played notes, and something very surprising takes place in the merging of the individual notes, something beyond your control, to an extent, but which, through a lot of practice, can be consciously ‘fabricated’ as a part of what you’re doing.

DM In an interview, you once said in reference to your iPhone: ‘I can always be reached, I couldn’t imagine it otherwise.’ Doesn’t that contravene the sense of contemplation your music exudes?

HJR I don’t know. But I also play with an iPad. I don’t need much more these days in terms of electronics. The iPad and the possibilities offered by the software on it, Animoog and Traktor, have taken over almost everything. Only the grand piano is irreplaceable.

DM Tim Story, one of your many musical collaborators, once said that you were the most intuitive musician he knew. What does intuition mean to you?

HJR I can’t do anything else, thank God. I don’t carry the baggage of musical history on my shoulders. The only thing I can do, or want to do, is to wait until something develops independently while playing, until something happens out of the moment, and in a form that generates meaning. Open and unpredictable.

DM What role do your fellow musicians play in making music?

HJR That’s a completely different subject. Another person is a whole other universe. Your relationship to that person has to be just right, a priori. You have to like each other, you have to share certain values: family, friendship, the ability to withstand conflict and debate. From 1969 onwards, Moebius and I maintained a friendship that, through collaboration and personal knowledge, became deeper throughout the ages. Yet sometimes collaboration just doesn’t work, in spite of all the other things that are right. That’s how it was with Peter Baumann from Tangerine Dream, for instance. He thought he could produce us and work out our music’s potential to make it more marketable. But it didn’t work, at least not for me. I fell ill during the production with Peter on Jardin au Fou (Garden of Madness, 1979) and Lustwandel (Change of Lust, 1981). And Peter got sick, too. In his studio, which even then was highly modern, with a Steinway and elaborate equipment, it just wasn’t possible to play like I did in Forst, in the quiet of the night, with frogs croaking and horses whinnying right outside the window. Neither of us was to blame that it didn’t work. And even if people always find it ridiculous. In the end, art still has to be made for its own sake – and not to satisfy deliberately determined market demands.

DM You can already hear the importance of nature in this anecdote. It also turns up again and again in the titles of your albums: Flieg Vogel fliege, Wenn der Südwind weht, Wasser im Wind (Fly Bird Fly, 1981; When the Southern Wind Blows, 1982; Water in the Wind, 1982). What role does nature play in your music?

HJR I was tired of all the never-ending synthetic sounds you hear everywhere. Sometimes they caused a real sense of unease making me feel sick. I worked for a time with a Korg MS-20, for instance, and I played around with frequencies that were clearly harmful to the body, as it turned out later. I literally played myself sick, and then I had a stomach ache for half a year. For a long time I didn’t know what was wrong: I ate well, went into the woods to chop wood, but my stomach wouldn’t cooperate. And then I put the thing away and sat down at the piano, and all of a sudden everything was fine! I sold the Korg. Forst was a kind of paradise for me. We had to go into the woods to chop kindling for heating, we had to bake our own bread, make marmalade. We didn’t have any money. When I say ‘back to nature’, to me it means a certain kind of attitude towards life. I was fairly confused as a child and a youth, because of the war. Actually, from 1943 until the early 1970s, I was pretty much on the road. I felt this huge restlessness until we settled in Forst in 1972. It was the first time I felt any quiet and serenity in my life and as a result I made more harmonious music than I’d made ever before …

Translated by Andrea Scrima

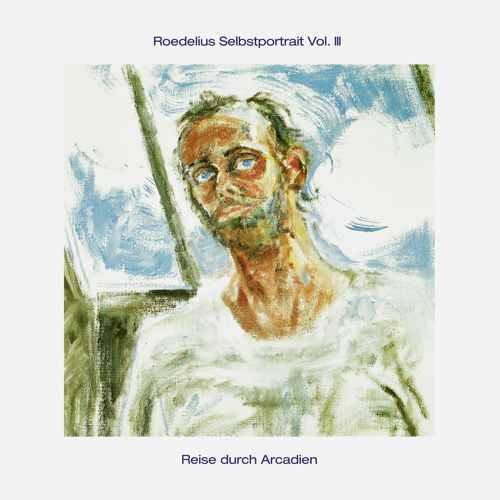

Hans-Joachim Roedelius was born in 1934 in Berlin. A member of the bands Cluster and Harmonia, Roedelius also received acclaim as a solo musician. The Lifelines festival takes place at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin from 3 – 6 September.