Marrakech Biennale 5

On my recent visit to Marrakech, I inadvertently kept repeating the title of its fifth biennale, ‘Where Are We Now?’, while attempting to navigate the city’s labyrinthine medina. Pondering the prevalence of biennials around the world and wondering what (soft power or white-wash?) and who (locals or the international jet-set?) they’re for also prompts the question.

The biennale was organized around visual arts, performance, literature and cinema, under the artistic directorship of Alya Sebti. The dynamic curator of the visual art section was Hicham Khalidi, who is Dutch-Moroccan, which helped, as staging such an exhibition in a country that is, in many ways, a stranger to art’s more radical impulses, is complex. Although Morocco is officially a democracy, criticizing the king – who, this year, for the first time, is the biennale’s patron – is taboo; the country is ranked a dire 136th out of 179 countries in the 2013 Reporters Without Borders press freedom index, and homosexuality is illegal. In an interview earlier this year in the Financial Times, Vanessa Branson, the founder of the biennale, was asked: ‘Last year Qatar, which has one of the most high-profile arts programmes in the Arab world, sentenced the poet Muhammad al-Ajami to 15 years in jail for criticizing a former emir. Is there a danger that autocracies use art simply to dignify their appalling regimes?’ Branson replied: ‘The arts can at least help to get some debate going. Artists by their nature enjoy being honest – often brutally so. I’m convinced they can play a very important role.’ Well, yes and no. It depends upon what they’re allowed to be brutally honest about.

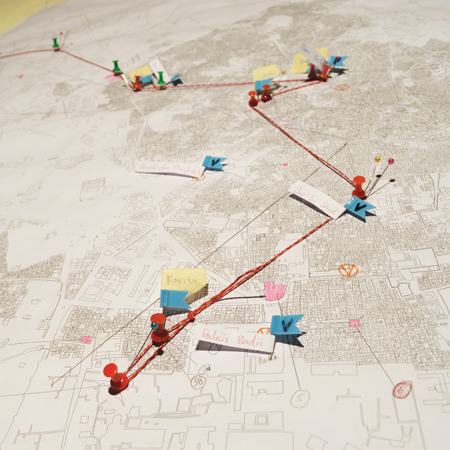

Despite my exhaustion with the use of the word ‘identity’ in contemporary art, the biennale’s subtitle ‘Identity as potential. Identity as fiction’, neatly sums up the confusions of a country struggling to reconcile its past and present with the possibilities of a modernizing future: the king has declared he would like 20 million tourists a year to visit Morocco by 2020. Khalidi posed his apt question-as-title in three local languages, Darija (Moroccan Arabic), English and French, and invited around 40 artists – about a third of them women, and many of them local or with strong links to the region – to create work that was ‘produced in and inspired by the context of Marrakech’; much of it unsurprisingly dealt with issues around economy, tourism, post-colonialism and migration. Venues included the staggeringly atmospheric ruins of the 16th century Palais el Badii; the Museum of Moroccan Arts, Dar Si Said; the former Bank Al Maghrib, which overlooks the famous square, Jemaa el Fna; and L’Blassa, an abandoned art deco space. Around 20 art works were specially commissioned for the show and most of them were site specific. There was also a music programme by freq_out, a group of international sound artists, who performed in the cavernous space of the Théâtre Royal de Marrakech, which remains incomplete after 25 years of construction. The biennale also included a strong education programme and, when I visited, the venues were filled with local families and children. What a lost opportunity, then, that the wall texts were written in often-impenetrable jargon. Why is such boring and bewildering language so endemic in the art world?

Despite the uneven quality of some of the work, the biennale was host to many highlights. These included Éric van Hove’s extraordinary V12 Laraki (all works 2014), a group of sculptures at Dar Si Said based on a Mercedes Benz engine, which was manufactured by local craftspeople in 53 materials, ranging from fossils to goatskin to terracotta; and the brilliant African Fabbers project in L’Blassa, a programme of workshops which aims to link design, art and architecture communities across Africa and Europe. Much of the strongest work employed sound, such as here, now, where?, an ‘urban sonic journey’ by Younes Baba-Ali and Anna Raimondo for Saout Radio that could only be experienced in a taxi; Mounira Al Solh’s In Brown, Longtime Thresholds and Substrates without Catalogues, which explored translation as a series of songs; Asim Waqif’s enormous interactive sound sculpture The Pavilion of Debris, Cevdet Erek’s Courtyard Ornamentation with Sounding Dots and a Prison, which sonically mapped the haunted spaces of Palais Badii, and Hassan Hajjaj’s transformation of the foyer of L’Blassa into a music-filled café. I was sorry I didn’t get to see Clara Meister’s Singing Maps and Underlying Melodies, which employed local musicians to replace maps with sound; and Saâdane Afif’s performance Souvenir (La leçon de géométrie) (Remember, the Geometry Lesson), which involved the artist talking about geometry to anyone who wanted to listen. All of these works were vital, relevant and imaginative. If they’re an indication of where we are now, then all, it seems, is not lost.