Mateo López

A modest Colombian shoemaker makes his way north to Mexico City some time in 2007. After wandering through the most populous city in Latin America, he finally sets up a shop, quite logically, in a big red shoebox, which stands to one side of the shoebox-like space at the KBK gallery’s new location, a former chocolate factory in an industrial area undergoing rapid gentrification. (Just a few blocks away, a new branch of the Soumaya Museum, owned by the Mexican tycoon Carlos Slim, and a satellite venue for the Jumex Collection are both under development.) The shoebox is in fact a replica of Mateo López’ Portable Workshop # 25 (2007), a fully equipped studio (including a camera lucida) that fitted on the artist’s 1994 Vespa scooter, a vehicle sturdy enough to transport him over the rough roads of Latin America earlier this year, all the while making dibujitos: small or unimportant drawings of the landscapes, architectural details or handmade billboards he discovered on a journey reminiscent of those of 19th-century travellers such as Baron Alexander von Humboldt or Frederic Edwin Church.

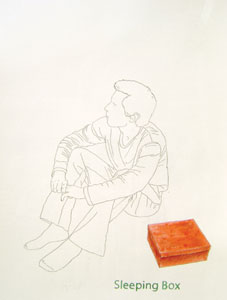

For the artist-turned-peripatetic-shoemaker this Sleeping Box (2007) is just a bit fancier than an austere camping tent: inside are a folding campbed covered with a sleeping-bag, a simple chair with left-over breakfast on it, a plain white shirt hanging from a wall, a useless LP floating next to a pillow, and a prominent desk that fills over two-thirds of the space. The desk is covered with artists’ tools and old-fashioned shoemaking implements: notebooks, pens and pencils, scissors, cutting instruments, a magnifying glass, a fancy tube of French glue, a red shoebox and, of course, an unfinished pair of shoes. The arrangement is impeccable: precise, theatrical, hyperreal. In fact, however, every single object in this inventory of a supposed ‘crime scene’ is made of paper cut-outs, carefully drawn and coloured. They find their echo in the two-dimensional drawings that replicate the same objects from different points of view and which hang in the gallery, both inside and outside the box.

In 2006, for his first solo show at Bogota’s Casas Riegner Gallery, López worked for a month in front of the public, replicating every single object in his studio on pieces of paper, one after the other. This blending of (semi-) public performance and gallery show was designed to challenge the basic idea of art as commodity: like some sort of Penelope, López reproduced every object that was sold during the exhibition in order to maintain the integrity of the overall ‘model’ (or facsimile) of his studio. By the end of the show there might have been drawings of two or three pairs of scissors or glue tubes in the hands of collectors, in addition to the originals remaining in his actual studio, which necessarily acquired new meanings – and changed in market value – after being re-presented so many times. But López was actually selling not so much ‘conceptual’ objets trouvés as his skill as a draughtsman and replicator.

The self-consciously naive narrative of a Colombian shoemaker finding success in the complicated spiral of the current Mexican art world also addresses the very meanings of art. On the one hand López explores the issue of mimesis, which leads him to create unstable (and extremely fragile) ‘three-dimensional drawings’ that look as if they were reflected in a distorted mirror (there is something magical that reminds us of Lewis Carroll’s displacement of objects, which undermines the idea of hyperrealism). On the other, he exposes the intimacy of the artist’s studio, a space that is now being represented not in terms of the artist’s imagination or compulsions but as a slap in the face of the curator who is looking for secrets to write about when actually one finds nothing but plain, simple and neat images on the flat surface of the graph paper.

The title of López’ Sleeping Box serves as a multivalent pun on the attempt to make art at a ‘post-Conceptual moment’. As the Spanish saying goes, ‘zapatero a tus zapatos’ (‘to the shoemaker, the shoes’): to each his own. In his exquisite diagrams, which attempt to explain how a skilled Colombian shoemaker came to settle down in Mexico, López makes drawings perfect enough for the draughtsman. He also reminds us that ‘a shoebox should contain shoes’, which might be understood as a comment on Gabriel Orozco’s gesture at the Venice Biennale in 1993, when the leading Mexican artist of the time placed an empty shoebox in the middle of the Aperto. Orozco’s Empty Shoebox, which did not even have a ‘real title’, theatricality flattened artistic categories, challenging the very function of art. But like some rectangular set of Russian dolls, López’ massive red shoebox is anything but empty: it holds several smaller boxes inside, each of which contains others, or contains series of drawings of other shoeboxes that serve as supports for more drawings and diagrams of boxes. López thus questions the ‘empty meaning’ of that more famous shoebox, reciting, à la Gertrude Stein, that a shoebox is a shoebox is a shoebox.