Starting Over

How inmates of a young adults’ prison near Bamberg recreated a piece by Charlotte Posenenske

How inmates of a young adults’ prison near Bamberg recreated a piece by Charlotte Posenenske

We’ve been working under the name ‘zwischenbericht’ (Progress Report) on projects about art and public space since 2005. In 2009, a Kunstverein in Nuremberg, Zentrifuge, invited us to develop an exhibition in the former AEG turbine factory in the city. We called it ERFAHRUNGsPRODUKTion (EXPERIENCEsPRODUCTion). The expansive and empty walls of the factory still exhibit traces of machines – the footprints of 150 years of industry. We filled these outlines with references to works by important modern and postmodern artists and shared the central ideas of these works through tours of the factory and an exhibition. The German minimal and conceptual artist Charlotte Posenenske (1930–85) was one of the artists represented. That was how the trustee of her estate and onetime partner, Dr. Burkhard Brunn, got to hear of us and took an interest in our work.

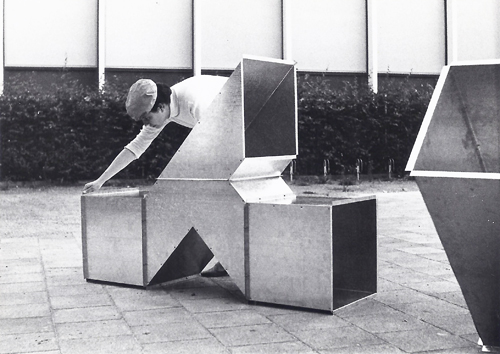

Shortly after this, we worked on a project in Bamberg. At the opening, we met Christoph Gatz, an architect who was active in the local Kunstverein. Bamberg is a very traditional and relatively small town. Almost everyone there involved in art knows each other but newer-than-medieval art tends to be treated with mistrust. Upon opening our Nuremberg catalogue, Gatz remarked: ‘we need something like this here.’ This led to the idea of connecting Posenenske’s work with the city. The result was our several-stage project WERKsHANDLUNGen (WORKingOPERATIONs), which we began in 2012. Initially the components of Posenenske’s Vierkantrohre Serie D (Square Tubes Series D, 1967) were rearranged each week by young adult prisoners in Ebrach near Bamberg and later they created a replica of the original. An exhibition with Kunstverein Bamberg followed in June 2014, along with a symposium.

In one of her manifestos, Posenenske writes that, ‘art objects should have the objective character of industrial products. They are not intended to represent anything other than what they are. The former categorization of the arts no longer exists.’ She wrote this in 1968, shortly before giving up art to be a sociologist. Since then her works have been shown in the world’s biggest museums, where they are staged similar to a Donald Judd piece: as a sculpture not to be touched, their interactive aspect lost. Posenenske created prototypes and designs that were explicitly meant to be reused. The original would disappear; the artist would vanish. We wanted to explore the possibilities of blending the originals with the new.

Our project in Bamberg was created through a framework of encounters and discussions with people from various fields. At one point, it was recommended we talk with Hans Lyer, a chaplain at Ebrach who initiates art projects with inmates as part of his therapeutic work. We showed him Posenenske’s manifesto and he invited us to visit.

The prison in Ebrach is 40 kilometres from Bamberg and housed in an ancient monastery with an immense church. The monastery is home to 300 inmates between 18 and 25 years old. This was our first visit to a prison and we wondered how the prisoners must feel. Did they think a lot, like we artists do, about freedom?

There are several versions of the square tube sculptures. The trustee of Posenenske’s estate, Dr. Brunn, allowed us to use one of the original sets – 36 units, six of each a different type of shape – and transport it from storage in Berlin to Ebrach. We asked ourselves what on earth would happen when we let young prisoners handle such fragile, sharp-sided pieces. We weren’t sure of the prison’s safety standards. There were many questions.

The inmates were allotted time each Sunday to screw the modules together however they liked, and then take them apart again. We were there occasionally, but most of the time we weren’t. Our approach required us to remain out of the process entirely. Volunteer helpers documented the project for us. Because of Germany privacy laws, it was important that none of the inmates could be identified in the pictures or videos.

The prisoners understood that they were working with the units to create art and that we, as artists, were providing them with a framework and opportunity to do so. We weren’t interested in any kind of didactic approach, but rather in providing a practical nudge: the construction kit was there, why shouldn’t something be built with it? Our work consisted of driving to Bamberg and Ebrach three or four times a week to coordinate appointments and keep everyone up-to-date on progress. We lost count of how often we drove back and forth and how much time the project took.

Throughout the assembly stages, the inmates discussed their lives and drew analogies: ‘I’m in jail now, but I can change my life, just as I can change how these units are assembled.’ The results were diverse: some were independent sculptures, others related to the layout of the room.

The dimensions of Posenenske’s units are such that they can’t be arranged by one person alone. This made cooperation necessary which created social groups and hierarchies – whoever had a construction idea naturally wanted to see it made. Several groups of inmates were building alone until they were directed to work together.

Each side of the original units, made of tin, contains two small holes for screws, so there are eight on each unit. An eight millimetre wrench is the only tool necessary to combine the units any which way. The rectangular shapes are quite elegant and though they were designed for frequent rearrangement, they are also relatively fragile and showed evidence of use after just a short while. Posenenske also worked with paper. One of her earliest pieces was a sheet of paper, folded in the middle and hung from a wall as a sculpture. She carried this lightness over to her metal work.

At some point in the project, the idea arose to create a replica of the original structure. This replica of Vierkantenrohre Serie D was built in the metal workshop of the prison. At Ebrach ‘work’ is a central concept. The inmates gain instruction in a trade and the apprenticeships are of a high standard. The master-builder of the metalworks division spent a long time fiddling with the construction of the replica to develop a curriculum for his apprentices. He found it unacceptable for example that the edges of the original were sharp enough to cut. He didn’t see the aesthetics of it, only the potential dangers. That’s why his versions of the replica were triply-reinforced with thicker screws.

Our agreement with Dr. Brunn required the replicas to be either 20 percent smaller or larger than the originals. For us, logistically, the project ended with the exhibition at the Kunstverein Bamburg and the symposium, in which both construction kits and various documents from the building process were on display. But in a way, the project lives on.

The prison now has its own construction kit and it is always available for rent.

Translated by Yana Vierboom