Sean Landers

On Sean Landers' first visit to the Medici Chapel, what impressed him most were cartoons by Michelangelo scrawled on to unfinished plaster walls. Landers saw more humanity in this minor form by the great master than in anything else there. The doodles, half-animal half-human amalgams, provided a pure glimpse into the truth of Michelangelo. Therein, the 'truth of the artist' would become Landers' own life's pursuit.

In his latest exhibit at Andrea Rosen Gallery he's at it again. Large text paintings are back with a vengeance accompanied by a group of bronze sculptures - a confederacy of dunces - both stoic and fantastically absurd. The painted texts, of varying colours and sizes, read differently on three types of back-ground: clouded skies, pitch-blackness and white.

The writing on the white paintings is most familiar. It records the artist's thoughts as he makes the paintings.As opposed to his earlier more graphic paintings, these are exploded open and bursting with colour. We've entered his skull conceptually and visually. Words and phrases ricochet off the walls of his cranium and we are among the brushstrokes, like Clement Greenberg imagining himself sailing through the drips of a Jackson Pollock. In them we find elation, despair, self-aggrandizement and self-loathing - all the good manic-depressive stuff of a genuine artist. Landers has always had an uncanny knack for portraying himself so well that one inevitably sees oneself. Frankly, the last artist to do this as effectively was Rembrandt. Within the saddening eyes of his ever-ageing self-portraits, we identify with the little bit of hope that is most crushingly tragic, most telling of life's ultimate hopelessness. Similarly, in Landers' paintings it is this same glimmer of hopefulness that makes them so telling, and worthy of our empathy. It is the lament of Icarus when his feathers began to melt off of his arms. It is the frustration of the certain and endless failure of Sisyphus, the panicked imprisonment of the Minotaur and the futile gaze of Narcissus.

Landers' black paintings are distinctly more paranoid and self-ridiculing; like thoughts late at night or behind closed eyes in the course of an anxiety attack. They are repeated, illustrating the mind's obsessive echoing assault against itself, while creating the illusion of depth. They appear like neon signs look at night to the double-vision drunkard being harangued by thoughts of his own crushing failures, both real and imagined. They are self-parody - echoes from an earlier moment in Landers' artistic creation, stared at back in time, as if through the Hubble telescope at the 'Big Bang'. His ostensible ineptitudes lurch forward as half-believed and discarded slogans from bygone days recede into the blurry distance like galaxies too distant to care about.

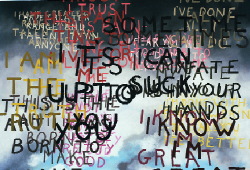

Then there are the sky paintings, which are like lost prayers searching for sympathetic ears in a godless heaven. Landers, raised a Catholic, was trained to pray as a youth. In It's up to you (2003), in lieu of God, Landers is praying directly to his audience to convince them he is the greatest artist alive. A dubious claim perhaps, but an essential belief for an artist. The sleep of reason produces monsters (2004) is angry at an uncaring world ('Kill Me', 'Betray Me', 'Blame Me'), but it's Landers' hopes ('Love Me', 'Reassure Me', 'Need Me') that make us cringe for him. Unrequited longing for audience recognition is both heartbreaking and humiliating. Humiliation is the currency with which he buys our affection. The words in this painting rise from some unknown darkness to torment him like the bats in the famous Francisco de Goya print after which it is named. In There was a time ... a painting meant to be most meaningful only after his death, there is a poetic definition of art as Landers knows it. He believes art is the depositing of bits and pieces of artists' souls into objects that can survive them, which for Landers is the successful transference of prayer into art or of soul into afterlife. He sends his art into time like prayer to a deity. For Landers that deity is the future of humanity. He's not talking to us, he's addressing future audiences. We are bystanders at this performance. His art is his time capsule of himself into the future, and truth speeds his passage. What was true of humanity for the Greeks, for Shakespeare, for Michelangelo, is true for us now and will be for 500 years, even 5000 years.

Which brings us to his sculpture. Art made in bronze is on an unstopp-able course into time. So what does Landers send on this mission? Irreverent fantasy creatures to entertain his kids? Of course! What could be more salient than that? What are children but vehicles of life? Links on the chain from Lucy into the unknowable future. They are an incarnation of our eternal hope, that very same sad glimmer in Rembrandt's eyes, the true reflection of Narcissus' gaze, the perpetual new beginning for Sisyphus, the glorious attempt of Icarus and freedom for the Minotaur. His bronzes are his progeny for his progeny. They are his hope sent forward in time, his version of his first true discovery of Michel-angelo's actual humanity. And last, they are a record of his performance on this stage, one at times warped by delusion and fantasy and fig leafed by occasional fiction but ultimately, it is him. He is this person.