Currents: 3D Printing

The first 3D printed gun was fired in the US recently. A starting pistol for the technology’s rise and dissemination? Perhaps, but artists have got there first

The first 3D printed gun was fired in the US recently. A starting pistol for the technology’s rise and dissemination? Perhaps, but artists have got there first

In simple terms, 3D printing is an additive manufacturing process. A digital 3D model, drafted on a computer, is sent to a machine that translates the code into microscopic layers of material and binding agent to eventually build a 3-dimensional form. The procedure might be analogous to a sedimentary rock formation accelerated into minutes rather than years. As products of addition rather than subtraction, contrary to Michaelangelo’s famous quip that ‘every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it’, these sculptures are born pre-formed.

In the past few years, artists as diverse as Oliver Laric, Peter Coffin and Barry X Ball have been using 3D modelling and scanning techniques that can be loosely grouped under the term rapid prototyping – crucial for the technology’s other application: 3D printing itself. Laric first used the process for his work Icon (Utrecht) (2009). The artist sent photographs of such an icon to 3D modellers, whom he frequently works with, who built a digital 3D version. Through a process of laser sintering, this was made into a silicone mould and, ultimately, into a series of vivid polyurethane sculptures. For the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011, Barry X Ball presented a series of sculptures in various types of translucent stone, ‘copies’ of Baroque masterpieces: Antonio Corradini’s La Purità (Dama Velata) (1720–5), for example, that was digitally scanned then laser cut using the digitally-rendered model. Coffin’s Untitled (Shoe) (2009), included in the group show The Still Life of Vernacular Objects at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler last year, showed, on two side-by-side plinths, a found shoe and an alien version of it – heel upturned and morphed into a foetus.

(courtesy: Tanya Leighton, Berlin)

If these 3D modelling techniques are the forerunners to 3D printing proper, then a number of recent shows in Germany have pushed the technology from the pre-production stage of scanning and modelling to the various 3D printing manufacturing processes themselves.

A pioneer of the technique is Karin Sander, who in 1996 began researching rapid prototyping technology in collaboration with the University of Utrecht – one of the few universities and private institutions researching the subject. In her current shows at the LehmbruchMuseum in Duisberg the artist exhibits close to 1000 miniature 3D ‘portraits’ of museum visitors, Visitors on Display (2008–13), presenting in multicoloured plastic a crowd of visitors to exhibition-goers themselves. Both the concept and sheer number of pieces comprising this project point to the immediacy and ease that this technology allows the artist, something also reflected in the work’s own theme of serialization and crowds.

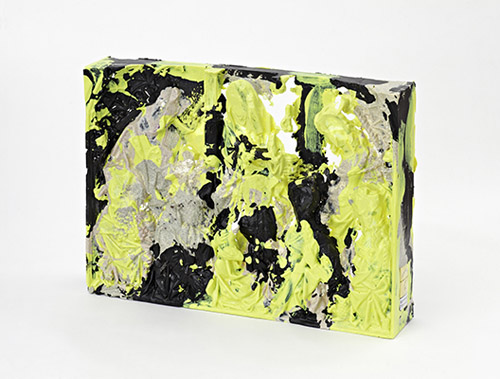

In Berlin, Aleksandra Domanović, in her current show at Tanya Leighton Gallery, printed five variations of the ‘Belgrade hand’, invented by the Former Yugoslavian scientist Rajko Tomović and one of the earliest functioning robotic hands. Tomović designed this as a prosthetic for soldiers who had lost hands in the Second World War, but Domanović showed her models in different configurations, from an Indian gesture symbolizing fertility and love to a closed fist holding a wooden baton – ciphers to explore and reassert the overlooked position of women in modern technological development. Similarly mining the past for models, in his solo show exhibition at Future Gallery, Jon Rafman showed a 3D printed sculpture NAD (Zigzagman Malevich) (2013) – the first physical sculpture from his series New Age Demanded (2011–ongoing) – made as a digital rendering of a classical Greek bust overlaid with a Kazemir Malevich scribble. Yngve Holen’s recent show at Société zoned in on the 3D production process itself. A design for a unique security screw titled Hater Head was then 3D printed using the process of direct metal sintering. The artist simply presented the screws, the drill, and a drill bit on a shelf in the gallery space along with a video animation of the screw, which – like the non-user serviceable screws in Apple products – Holen could uniquely render and produce using this technology.

The possibility of creating objects using widely available and easily programmable software seems a liberating and democratizing one. Ethical questions of the open source access to the first 3D printed gun design aside, the possibility of pre-made 3D scans, easily accessible and printable, opens up an archival, archaeological treasure trove, much like the PDF format did for the dissemination and printing of documents and books. Laric is currently working with the The Collection and Usher Gallery in the UK to make 3D scans of their entire collection, comprising some two million pieces. This will then be a free online archive, with the possibility of printing the models, opening up the collection to the unprecedented possibility of numerous, almost perfect copies of the same object existing in circulation. One of the leading 3D manufacturers, Shapeways, based in New York with offices in Eindhoven, has started an online marketplace for artists and designers to buy and sell 3D printed designs that are then fabricated by the company in a seemingly limitless range of media.

While it would be simplistic to fetishize the technological process itself, it seems the technique mirrors in some small way the additional, accumulative nature afforded by the Internet’s flat ground economy. It’s 60-odd years since the US inventor and patent lawyer Chester Carlson invented the technique of electrophotography – the technology behind the Xerox photocopier – frustrated with having to copy out longhand from law books in the New York Public Library while studying for his law degree. Sixty years from now, will 3D printers be just as common, or just as obsolete?