Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Champaign, USA

Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Champaign, USA

Encountering Theresa Hak Kyung Cha's work for the first time can be a disorienting and perplexing experience. Yet perhaps this is inevitable when viewing the work of a young Korean-American artist who spent her all-too-brief career producing evocative works that examined the ways in which the present is always infused with the past and how our identities are framed by language.

Cha was a dedicated student of many things: Conceptual and Performance art, film theory and practice, linguistics and literature. Her output spanned a heady period from the early 1970s to her death in 1982, and the current travelling retrospective, curated by Constance M. Lewallen, offers an extensive selection of artworks in the form of photographs, videos, statements and paper projects.

While Cha is most famous for her posthumously published experimental novel Dictée (Dictation, 1982), in this particular exhibition visitors were asked to construct an impression of the artist's visual work from a series of glimpsed fragments. Some pieces make this easier than others, but the fact that among the strongest works by Cha were performances - which now only exist as rough documentary photographs - serves to distance the viewer further from the work.

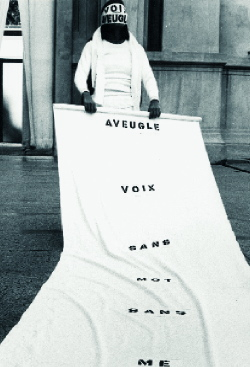

Throughout the 1970s Cha used her ritualistic performances to convey an ethereal, luminous state not unlike that of early cinema. The exhibition's title, 'The Dream of the Audience', is drawn from the artist's statement regarding A Ble Wail (1975): 'In this piece I want to be the dream of the audience.' Cha performed the piece behind a cloth screen that separated and obscured her from the viewers. In Aveugle voix (Blind Voice, 1975) the artist blindfolded herself with a headband inscribed with the word voix and covered her mouth with another headband inscribed with the wordaveugle. In Barren Cave Mute (1974) each word from the title - transcribed in white wax on a 10 Ý 4 foot sheet of paper - became briefly legible with the aid of a candle, before bursting into flame and becoming a pile of ash on the floor. The quasi-mystical procedures of Cha's performances recall certain aspects of traditional Korean Shamanism, which features women priests (mudang) conducting rituals incorporating trance possession.

Cha's videos were without doubt the most mesmerizing and arresting pieces on view, in large part because nearly all of her work seemed to revolve around film and its structural aspects: the edit, the frame, the title, the montage, the dissolve. Mouth to Mouth (1975) presents a close-up view of lips mouthing Korean vowel sounds, which dissolve in turn into the white noise of television static, which is in turn followed by the reassuring sound of running water. It's a riveting piece, communicating as it does the inescapable qualities of language - we are always submerged within its watery depths. The theme of water is a recurrent one in Cha's work, as in Re Dis Appearing (1977), in which depictions of a bowl of tea resonate with ideas of transparency and entrapment.

In an approach similar to her videos and performances, Cha's text pieces - both visual and aural - explore the relations between dualities: subject/object, light/dark. The first page of Presence/Absence (1975) declares, 'water fills up the empty places'; it is followed by a family portrait, which is repeatedly photocopied, leaving a mottled texture recalling bubbles, ripples or grains of sand. Listening to the haunting spoken component of the performance Réveillé dans la brume (Awakened in the Mist, 1977), one hears: 'everything is light/everything is dark [...] everything feels light/everything feels dark/everything feels light/everything weighs dark.' A chilling bicentennial piece features an American flag altered simply with the stencilled word amer (bitter). In many of these visual poems Cha attempts to resuscitate memory, to bring it forth and lend it an elegant material structure.

The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue are commendable attempts to promote awareness of Cha's work and clear a space for her in the contemporary canon. However, the essays by Whitney Museum curator Lawrence Rinder and filmmaker/theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha verge on hagiography. If only it were possible once again to view Cha as a lively young intellectual and artist rather than as the somewhat staid and beatified subject of this historical survey.